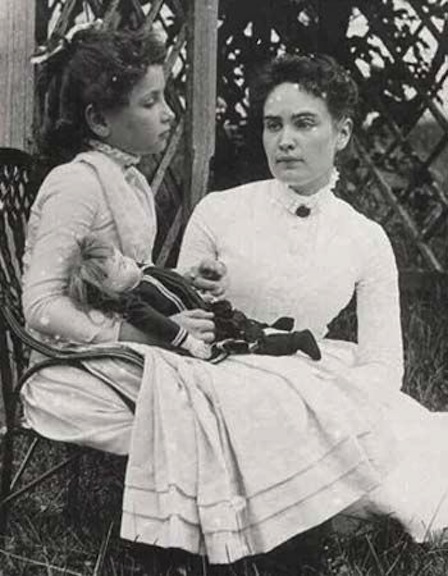

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan, photographed in 1888 in Cape Cod. Keller is 8 years old, and posed with a doll. (Courtesy of NPR/Pacifica)

The life and times of Helen Keller are so well-known in America that they are almost mythic. It’s almost impossible to know every little detail about a real person’s existence. However, legends and fairy tales allow us to glimpse a heroine’s misery and triumph, challenges and victories. We are there as flies on the wall. Helen Keller falls into that near-storybook category because of the beloved play “The Miracle Worker,” which is 60 years old this year.

Keller’s biography holds a very special connection for doll collectors. In William Gibson’s script, Anne Sullivan teaches pupil Helen Keller a variety of words. The first concept that Anne drives home is the word “doll.” Helen had lost her vision and hearing due to a high fever in infancy. From toddlerhood to the age of 6, Helen Keller lived in a world of silence and limited communication. Her family did love her, but they did not understand how to teach, encourage, and guide her.

Anne Bancroft, left, and Patty Duke are shown in character on stage in the Boadway play “The Miracle Worker” in New York City, October 1959. Bancroft plays the role of Anne Sullivan, who teaches the blind and deaf Helen Keller, played by Duke, to communicate. (AP Photo)

Living in wealth in Tuscumbia, Alabama, the Keller family resided on an estate called Ivy Green. Today, the buildings that remain, along with the water pump, are categorized as National Historic Places. (The pump is a crucial place in Helen Keller’s education. It is where Helen made the association between hand spelling and the object at hand.) Anne Sullivan, a visually impaired graduate of the Perkins Institute for the Blind, arrived at their home to teach Helen.

Traveling from Boston on her own, Anne had already defied a lot of society’s expectations. In 1887, most women were married or were raised to be wives of familial caregivers. They did not seek employment outside of their own homes. Most certainly, the average woman did not board a railroad, make connecting stops, and show up to teach. Truthfully, a visually impaired person of any gender attempting that journey 132 years ago is laudable. It was an amazing first step.

Bancroft as Anne Sullivan exhorts Helen Keller (Duke) to make the connection of “d-o-l-l” with “doll.” (Courtesy of Playfilm Productions/United Artist)

When Anne arrived at the Keller doorstep, she brought her bags, books, and a gift for her pupil: a doll. That doll was a tangible totem of Anne Sullivan’s whole teaching plans. She intended to let Helen grasp onto things that could be felt physically and emotionally. From that tactile connection, Anne proceeded to teach Helen how to spell. She wanted to elevate Helen’s “home signals” to universally recognized language.

Sullivan wanted Helen, who was blind and deaf, to make her needs known. To some extent, Helen could do that, but not in an approved and codified way. She also wanted Helen to understand that a single word can stand for more than just one item. The word “doll” means all dolls — not just one doll, not just Helen’s previous dolls.

Promotional photo of Patty Duke for her work in “The Miracle Worker.” Note how the dolls factor heavily in establishing Helen’s character. (Courtesy of Movie Star News)

In Keller’s book, “The Story of My Life,” she detailed the impact a homemade doll had on her. Her aunt made her a large doll out of towels. However, Helen was annoyed by the doll’s lack of eyes. She was willing to forgive her aunt for crafting such a “comical, shapeless thing, this improvised doll.” Its face had no nose, mouth, or ears, but it was the missing eyes that perturbed her.

Young Helen stole beads from her aunt’s cape and mimed that she wanted those for the doll’s eyes. After they were sewn on, Helen Keller said that she was overjoyed. Her happiness was fleeting, though. “Immediately, I lost all interest in the doll,” she wrote. This impromptu doll did not please her. Literary critics have theorized that Helen wanted to express to her family that blind people do have eyes. Mute people have mouths; deaf people have ears. She used the doll to drive that point home.

Doll artist Debbie Ritter created these two dolls of Anne Sullivan (left) and Helen Keller (right). Ritter is known by her Etsy handle, UneekDollDesigns.

The doll was Sullivan’s first invitation for Helen Keller to make an association between the hand spelling and an outside, unfamiliar object. The date was March 5, 1887, and Helen was three months shy of turning 7 years old. In later years, Helen Keller described this date as “my soul’s birthday.” This was a pivotal meeting in the two women’s lives. Their fates would be intertwined for the next 49 years. When Anne Sullivan passed away in 1936 from coronary thrombosis, Helen Keller was there, holding her hand till the end.

At Pennsylvania’s Media Theatre, Jennie Eisenhower as Anne Sullivan and Lexi Gwynn as Helen make the important “doll” connection.

Still, on the evening of March 1887, their interconnection was a long way off. Anne was determined to make Helen understand the movement of fingers on her palms. She wanted Helen to associate the spelling d-o-l-l with the doll. Looking back on it, Helen admitted that she had no immediate understanding. She attributed her mimicking of the finger placements to a “monkey see/monkey do” replication.

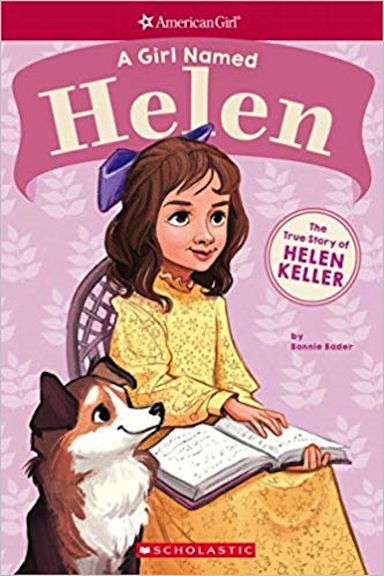

American Girl books pay homage to fictional girls as well as real-life historical figures. The doll company published a story of Helen Keller’s life for a very young audience. (Courtesy of Scholastic/American Girl/Mattel)

In 1888, 8-year-old Helen Keller and 22-year-old Anne Sullivan were on a school break in Cape Cod. A photographer took a picture of the little girl and her young tutor. Anne kneels beside Helen, who is seated with her doll upon her lap. Since the dawn of photography, little girls have posed with their playthings. For more than a century, a teacher has sat near her class for picture-taking day. This photo, however, resonates because it captures a pivotal object — a doll — and the two American legendary women.

This photo was discovered in 2008, 120 years after Helen and Anne posed together. The doll is a powerful symbol in Keller’s life.

The photo was not discovered until 2008. When it was uncovered, it became a visual testament to that portion of Helen Keller’s inspirational achievements. Here, Helen looks like a well-groomed, well-bred Victorian young girl. Anne, likewise, is an attractive, well-dressed young woman. They are both living, breathing people, not just characters in Gibson’s script and screenplay.

The doll that Sullivan gave to Keller did not survive long. In a fit of rage and frustration, Keller broke the doll. She could not accept that “doll” meant more than just her own singular, favored doll. She was not ready to make that leap of logic. Later, Helen Keller would write about this experience. “I was keenly delighted when I felt fragments of the broken doll at my feet.”

Dolls played a huge role in Helen Keller’s life. Artist Sophie Lewis created this Rainbow Peg Doll in honor of Keller’s extraordinary life.

When Helen finally had her breakthrough at the water pump, she felt regret. “I realized what I had done in breaking the doll,” she wrote. “For the first time I had felt repentance and sorrow.”

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the 1959 Broadway debut of William Gibson’s “The Miracle Worker.” Anne Bancroft, who won the Tony Award, starred in the production as Sullivan. The Theater World Award winner Patty Duke portrayed Helen Keller. The duo went on to play these roles in the 1962 big-screen version. Both Bancroft and Duke nabbed Academy Awards for their performances.

In 1979, Patty Duke portrayed Anne Sullivan and Melissa Gilbert took on the iconic role of Helen Keller. (Courtesy of Half-Pint Productions/MCA Television/NBC)

It is also 40 years since the premiere of the television movie version that featured Patty Duke as Anne Sullivan and Melissa Gilbert as Helen Keller. Duke had a lifelong connection to this story and would star as both Keller and Sullivan in different productions, in different venues. She would also direct the piece and produce it at various regional theaters. The story of Helen Keller impacted Patty Duke directly.

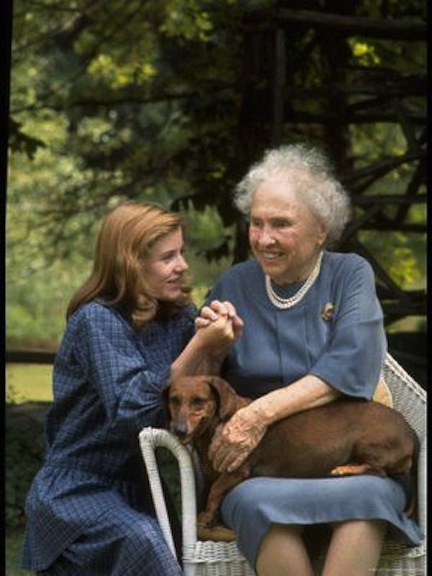

In fact, Duke met the actual Helen Keller while she was portraying her. Their encounter was photographed for a magazine profile of the actress who was embodying Keller’s childhood. “When I met Helen Keller, it was a high point in my life. To meet a real American hero is a moment that I can never forget. It was an encounter that I was touched by. Helen Keller’s words have always stayed with me: ‘The best and most beautiful things cannot be seen or touched. They must be felt with the heart,’” Duke stated.

Helen Keller and Patty Duke visit together on the movie set of “The Miracle Worker.” (Courtesy of PEOPLE magazine/National Archives)

For doll collectors, doll artists, and doll enthusiasts, it is an interesting tidbit that “doll” was the concept that shone light into Keller’s bleak world. Prior to Anne Sullivan’s tutoring, Helen described her life as “lost in fog.” She credited Sullivan with helping her to break out of her limited life and to explore options that surrounded her.

Many archival records, letters, photos, and recordings of Helen Keller were lost on September 11, 2001. These documents had been warehoused in the Twin Towers. Today, her story is enacted at regional theater companies and at Ivy Green in the summer. Visitors go to her birthplace and pay honor to a woman who achieved international acclaim and personal milestones.

Precious Moments commemorated women who made a difference in U.S. history. Helen Keller was one of their chosen inspirational women.

During her life, people sent her boxes upon boxes of dolls. Some of her dolls are on display at Ivy Green. The American Foundation for the Blind has a very meticulous list of the dolls that were collected by Helen Keller and who sent them to her. It is a fascinating look at the large number of famous and influential people touched by her story. These highly regarded folks (kings, ambassadors, movie stars, writers, presidents) decided to honor her with a doll.

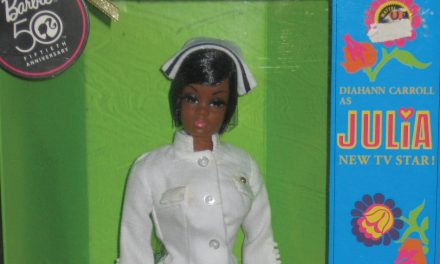

Mattel has their Inspiring Women Series of dolls that salute women of different eras and backgrounds. Perhaps there will be a Helen Keller and/or Anne Sullivan doll in the lineup. Just as Rosa Parks was an activist for civil rights, Keller grew up to be a leading advocate for rights for Americans with disabilities. She also tackled the women’s suffrage movement and demands for equal pay for equal work.

One of Helen Keller’s dolls on display at her birthplace in Alabama

Moviemakers and authors have often ignored Helen Keller’s political discourse. She was an admitted socialist, a proponent of mandatory birth control (eugenics), and a vocal champion for unions and corporate accountability. Some of her positions have become mainstream in today’s world. Meanwhile, many of her other beliefs are still considered radical by any measurement.

Their fates are forever entwined: Helen Keller as the bright pupil and Anne Sullivan who shone the light into the fog.

Helen Keller was a complicated woman, and her biography has been an inspiration for people of all abilities for more than 100 years. She is an inspiring woman, and so is Anne Sullivan. They deserve their place in American and doll history.