For 2019, Mattel is continuing to expand its Fashionista line to be more inclusive and representational of reality.

It’s a challenge for a doll company to produce toys that keep up with cultural shifts and demographic changes. It can be done, of course — after all, big businesses like Mattel employ a large group of artists and designers — but it is hard to know what should be promoted, what needs to become mainstreamed, what is reflective of who we are in the 21st century. As always, Mattel attempts to create new dolls that are less “idealized” than their original Barbie. With the teen fashion queen turning 60 this year, Mattel has renewed its promise to unveil dolls that are more about the somebody wearing the wardrobe rather than the shapely body itself. Mattel has pledged to promote dolls that represent Americans who are differently abled — people who live with physical differences and challenges.

Case in point: Mattel’s new Barbies that feature a wheelchair and a prosthetic limb. In an effort to make amends for a doll that often sent unachievable, preposterous messages to their young customers, Mattel is now re-examining their template for success. Rather than elevating the unattainable, Mattel will strive to focus on dolls that mirror people with more realistic body types, various skin, eye, and hair color, physical challenges, and different cultural edicts. Barbie is turning 60 years old, and she is finally waking up to the phalanx of non-blond, non-Caucasian, non-svelte collectors who populate her fan base.

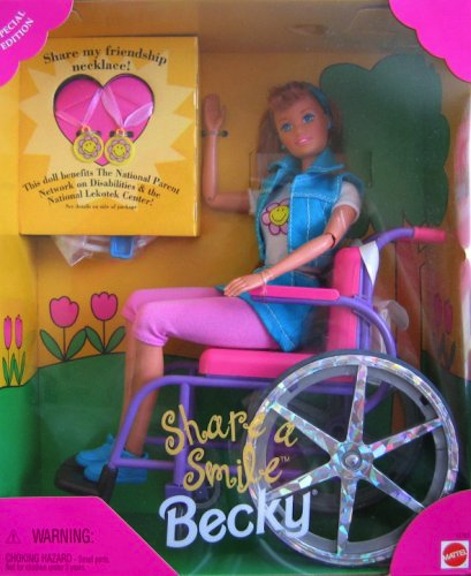

In 1996, Becky was Barbie’s friend. The doll was presented as a supporting player who was always spreading sunshine and a smile.

Interestingly, there was a Barbie friend from 20-plus years ago who utilized a wheelchair. Debuting in 1996, Becky was one of Barbie’s lesser-known friends. Featuring the 1995 Skipper facial sculpt, Becky was a classmate of Barbie’s who was popular and always cheerful, it seemed. In 1998, she debuted once more, and this time she had a personalized background story. Becky excelled as the school photographer. Her second doll set came with the wheelchair, yearbook filled with photos of the Barbie gang enjoying high school activities, and a pocketbook that hung on the back of her chair. Becky’s outfit was casual, consisting of a white T-shirt, jeans, plaid shirt, and red sneakers.

In 1998, many collectors were focused on the wheelchair and could not see beyond it. They were made nervous by this doll and her plea to join their collection or their children’s toy boxes.

At the time of Becky’s arrival, Mattel was not applauded for this act of inclusion. In fact, some folks viewed it skeptically or downright angrily. I remember writing about Becky for DOLLS magazine in the late 1990s and feeling I had to almost apologize for having a doll with a disability featured in our New & Noteworthy pages. Many readers scoffed at the idea of introducing anything that smacked of realism or suggested physical shortcomings. In the world of Barbie and Friends, everyone was supposed to be the homecoming king and queen, or at least the prince and princesses of the court.

If a collector had a troubled or unhappy adolescence, Barbie was there as a personable, peppy proxy. She would let you live out the life you hadn’t known; she was a surrogate for teenage happiness. It was as if the world was stuck in the late 1950s or early 1960s and every day was Prom Day, featuring a visit to the malt shop and a chance to gush about gowns and corsages. The world was vastly changing in 1999 — a new millennium was approaching — but the doll companies were still mired in an Eisenhower America.

In 1998, Becky was given an avocation. She was the school photographer.

Now, 20 years after Becky was dismissed as a ploy for attention — and a misguided one at that — Mattel’s new version of a girl with a physical challenge is being lauded. It shows how the world has changed in two decades. Furthermore, it’s not an innocuous member of Barbie’s posse that is being designed as an American with a disability. Rather, it is Barbie herself.

Slated to arrive in June 2019, the Barbie with a prosthetic leg and the Barbie who is mobile in her wheelchair are indications that Mattel is taking their Fashionista lineup in greater directions of diversity. According to their press release, Mattel stated, “As a brand, we can elevate the conversation around physical disabilities by including them into our fashion doll line to further showcase a multi-dimensional view of beauty and fashion.”

Jordan Reeves is an advocate for acceptance and raising the profile of people with physical differences and so-called disabilities.

To achieve this goal, Mattel worked with a team at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital to create a wheelchair that was realistic and reflected what a person with a physical disability would desire. “While there are many types of wheelchairs, this chair is modeled after one that is designed for an individual who has a permanent physical disability,” Mattel explained in their statement. They also listened to and collaborated with a child activist for people with disabilities.

Jordan Reeves was born with a left arm that stops above her elbow. She gained worldwide attention when she created a prosthetic arm that doubled as a glitter-shooting cannon. She and her mother, Jen, are the co-founders of the Born Just Right foundation, which advocates for children who are born with differences that can often make them feel ostracized or rejected. Mattel sought out the now-13-year-old Jordan as their quality-control expert and advisor.

A co-founder of the Born Just Right project, Jordan became famous for her glitter-shooting prosthetic. CNN celebrated her and her Project Unicorn devices.

Kim Culmone, Mattel’s vice president of Barbie design, was impressed by Jordan Reeves’s insight and reactions. Culmone realized that by listening to a member of the doll community — Jordan grew up with Barbie — she and Mattel could enhance their efforts to be more diverse and more empathetic. Jordan told Culmone that the prosthetic-limbed Barbie had to be able to remove it. Otherwise, it would just be a gimmick, not a true reflection of people who have prosthetic limbs. The limbs are removable; they are not fused to the person’s torso. “That is not necessarily something we would have realized how important it would be to someone living with this experience,” Culmone shared.

In a nation that often proclaims “if just one child is saved” or “just one child spared,” our toys have not mirrored that attention toward the “good of just one child.” In a manufacturing environment, where costs of goods, distribution channels, and bottom-line sales take precedence, it’s often been difficult to lobby for specialized or niche-market exceptions. After all, a company is in business to turn a profit, not to turn over society’s hang-ups or barriers.

Released as a special edition, Share a Smile Becky pledged a portion of its proceeds to charitable organizations that helped parents and children living with physical challenges.

So, the decision to create a Barbie with physical differences, and to promote it months before its release, speaks to the power of collective collecting. Mattel was made aware of how many people with disabilities and physical differences reside worldwide and in America. According to Jennifer Laszlo Mizrahi, president of the advocacy group RespectAbility, there are 1 billion people in the world with physical disabilities. “We want to see ourselves reflected in the culture, toys, products and everything around us,” Mizrahi said. “Barbie joins a number of powerful companies who also understand that marketing, and including, people with disabilities is both the right thing to do and the profitable thing to do.”

Close-up shot of 1998’s Becky who was the campus photographer.

In keeping with their commitment to make dolls that are in tune with the real world, and not out of synch with a changing society, Mattel is also looking to revamp its Barbie accessories. For instance, a Barbie with a wheelchair will require a ramp for her DreamHouse. The toy giant said that they will manufacture a compatible ramp for Barbie’s opulent manse. It is quite telling that in 2019, the doll company is aware that children and adult collectors are not interchangeable with one another. Even though Barbie is mass-produced, her fan base is not the same; they each have individual stories, struggles, and diverse backgrounds. The clue to inclusion is listening to these past-neglected collectors as they make their voices heard, and make their dreams known.

The 2018 version of Barbie’s DreamHouse. Going forward, Mattel will now make ramps that will be compatible to their over-the-top designs.

For a brand that always touted how Barbie could be anything, and dream any dream, finally more American children and adults are seeing that their dreams and their realities count for something, too. Barbie’s DreamHouse is finally opening its doors to more people. It is a big house, indeed.