As you get older, it’s interesting to discover how you are often bemused by what had once enchanted you. If you were a true-blue fan of “The Brady Bunch”—never missing an episode, and this was before the days of DVRs and even VCRs—it’s funny to view it as an adult. You can only shake your head and blame it on your youth. People’s tastes change, and people’s perspectives do as well. One exception, however, is the love affair that many women feel toward “Little Women.” A perennial go-to book as a classic of young-adult (YA) literature, this novel has maintained a grip on filmmakers, TV producers, theater composers, and doll artists, too. As a source of inspirational clothing, coiffures, and characters, a doll manufacturer can’t go wrong with the March sisters. In a collectible world populated by American Girl dolls, the March girls are the real deal.

Miraculously, Louisa May Alcott, the author, penned this tribute to sisterhood (the biological kind AND the feminist kind) back in 1868 when she was 35 years old. No longer a child or even a teen on the brink of womanhood—“Little Women” refers to the characters’ youth and inexperience, all standing at the threshold of adulthood, not their heights—Alcott was able to channel all of the feelings of vulnerability, jealousy, indignation, unrequited love, and feisty pursuit of self-worth and self-reliance. Even though she was middle aged by the standards of her day, Alcott was able to capture what it felt like to be on the verge of something great, maybe not something perfect, but something that was just right. (That’s a nod to Alcott’s sentimental exchange between Marmee and her strong-headed daughter Jo.)

The four sisters in “Little Women” are the perfect heroines to be converted into dolls. Each of them embodies a type—or an archetype, if you are philosophically inclined. It’s like Louisa May Alcott was psychic and knew that one day there would be a thing called the Internet and a website known as BuzzFeed. I can just see the personality quizzes keyed into the behaviors of Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy. (Question: If the handsome boy next door proposes to you, but you’re not sure you really love him, what do you? A. Try to thwart him, and feel guilty. B. Date him for a while, you never know with love. C. Take advantage of him to buy you nice gifts. He is rich, after all. D. Tell him it can never be. You’re very ill.)

Yes, I can see this so readily as a quiz, with A making you a Jo, B, a Meg; C, an Amy, and D, a Beth. Poor Beth, she never gets better, no matter how many versions of the movie are produced and distributed. That, I suppose, is what has made “Little Women” so alluring. It doesn’t disappoint, because it doesn’t change. Despite what alterations a director or screenwriter might bring to the text, to make it more palatable or personal to their mind-set, the essential story and the characters always remain true to their origins. That’s why they are such excellent dolls.

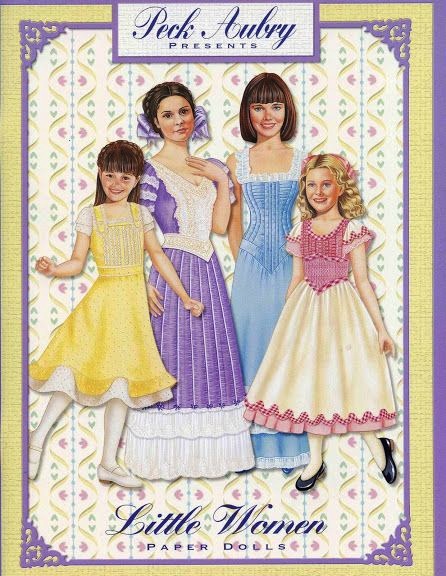

Just as Barbie is always pretty, fashion-conscious, and optimistic (is she an Amy?), the girls of “Little Women” remain tied to their creator’s intent. Jo is perennially spunky and pig-headed, but also goodhearted and altruistic. Despite her occasional self-righteous and selfish tirades, she is ultimately selfless and loyal. What doll artist wouldn’t want to sit down and sculpt such a multidimensional character! Even paper-doll artists have fallen under the spell of the March sisters and their devoted mother. The characters are all so fully formed that their many dimensions—their 3-D effects—are visible even in a 2-D version.

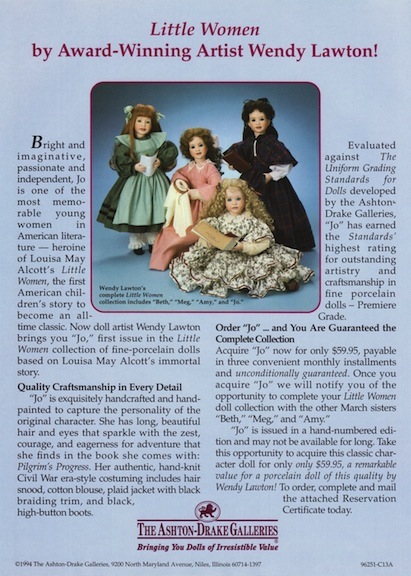

Over the years, Ashton-Drake unveiled versions of the March family, so did Madame Alexander, and Wendy Lawton (who sculpted the Ashton-Drake set) created a limited-edition version under her own company imprint. Manufacturers and artists have all gravitated to the dolls because they allow for a tribute to beautiful bygone costuming (the novel is set against the backdrop of the American Civil War) and also because it permits a feeling of making something good, and noble, and innocent, and wholesome.

On May 13 and May 20, PBS’s “Masterpiece” presented a three-hour adaptation of the novel. (It is being repeated on local PBS affiliate stations, and can be streamed for a complimentary brief time on its PBS website, after that it will charge for viewing.) The new 2018 depiction has a more mature and, at times, more somber feel to it than the 1933 Kate Hepburn vehicle or the 1949 June Allyson/Liz Taylor version. It’s not as visually lush as Gillian Armstrong’s 1994 depiction—that movie looked like a Hallmark greeting card sprung to life—but it is absolutely lovely to watch and ultimately draws you in. (The first 15 minutes seemed kind of iffy to me, but then it seems to pick up and finds a reason for its rhythm and makes sense of its editing choices.)

While watching this PBS miniseries with my daughter—and that made it special on a whole different level—I was happy that “Little Women” exists and is part of the American canon of enduring literature. Though it was written more than 150 years ago, it still touches on the basic dilemmas that young women face: social pressures, career choices, marriage versus singlehood (or as Jo terms it, “spinsterhood”), moral choices, and the strength of familial bonds.

“Little Women,” the book and this new TV drama, definitely hits home with the definition of “value” and “worth.” We see how less wealthy the March girls are versus their Concord, Massachusetts, neighbors, and we witness how they are often dismissed and denigrated because they need to earn a wage. (Meg labors as a governess; Jo as a writer of outlandish, melodramatic romances.) We at home know that the March family has value and worth; they just don’t have overflowing bank accounts. Their Christmas celebration, for instance, is about giving of one’s self more than the exchanging of gift-wrapped bounty.

Since “Little Women” is part of the public domain, and it is part of America’s consciousness, it can be tackled without fear of copyright infringement or estate approval. With that in mind, and realizing how its story is not controlled by licensing fees or corporate approval, perhaps some independent artists or companies will begin to re-examine these characters that have never gone out of style. The potential for Little Women dolls is limitless: there are five main females (four sisters and mother), several love interests (rich boy next door, soldiers, professors), and versions of the March girls as children, teens, and adults.

I hope the latest PBS interpretation serves as a match that will light the creativity among the doll artists out there. Marmee, Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy deserve to march on. Against all odds, and in front of a shifting cultural landscape, the March sisters do survive the ravages of time.