Close-up view of the Frida Kahlo, Inspiring Woman Barbie doll

Born more than 110 years ago (111, to be exact), Frida Kahlo has become more impressive and more inspiring over the last two decades than she even was in life. A painter who was revered for her blend of surrealism and portraiture, Kahlo often used her own likeness as a model for her otherworldly worldview. It was not unusual to have canvases that featured Kahlo with her limbs or torso replaced by vines or roots, animal hooves and paws, feathers or fur. She incorporated herself into her artwork, and her art slowly and totally evolved to define her. It’s no wonder, then, that Mattel’s Inspiring Women series boasts a Frida Kahlo Barbie, and it’s also not a surprise that it is totally sold out. Frida Kahlo has legions of fans who worship her talent and the larger-than-life existence she represents.

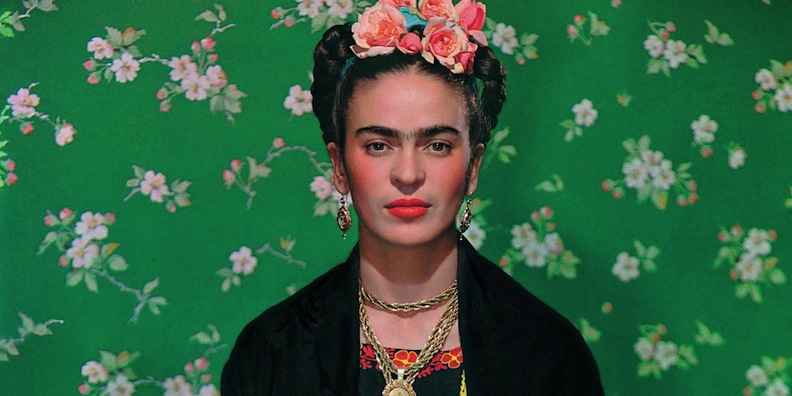

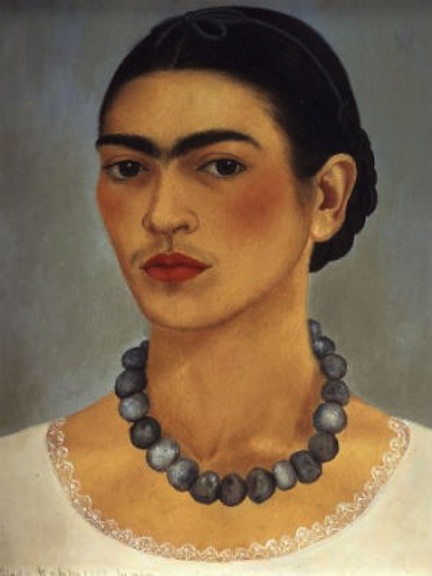

Photo of Frida Kahlo, the artist and the Mexican nationalist and feminist (Courtesy of BBC America)

The Kahlo doll, which was also priced at under $30, like the Amelia Earhart pilot, is a tribute to the folkloric image that Kahlo cultivated for herself. Born in 1907, she came of age during the era of flappers and Jazz enthusiasts, bobbed hair and higher hems. However, Frida was part of the Mexicayotl movement, which attempted to codify what it meant to be Mexican. Almost like a walking emblem or a mascot for her cultural identity, Frida took to wearing the bold colors and bright patterns of recognizably Mexican folk costumes. These ensembles became her daily wardrobe, which both solidified her attachment to her nation, and also made her an artist that stood out in the crowd. While many other women painters were Marcel-waving their hair, or dressing in provocative, revealing clothing, Kahlo took the alternate route. Her long, flowing skirts, and prim and proper blouses, sealed her identity as “the Madonna of Mexico.” (By Madonna, folks, the critics of the time meant the Virgin Mary, not the exhibitionist rock-n-roller!)

A close-up look at the Frida Kahlo Inspiring Woman doll from Mattel

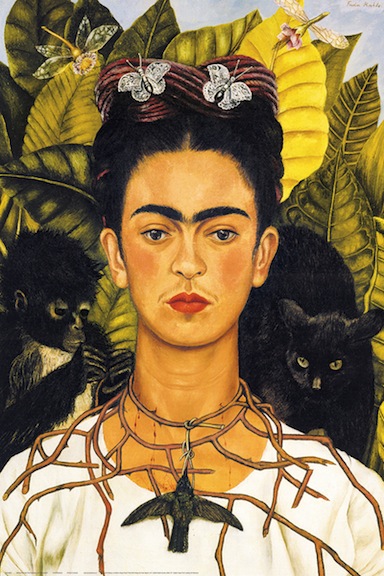

Frida Kahlo has attained fame because feminist art critics and professors began to study her life work throughout the 1980s. Having created almost 200 paintings during her brief 47 years on earth, Kahlo did not shy away from presenting herself in an accurate and nearly photographic truth-telling way. That is one of the puzzling dichotomies of Kahlo’s work. While she might be juxtaposing herself against a canopy of jungle foliage, accompanied by panthers, monkeys, and parrots—a noble queen amongst her rain forest subjects—she meticulously replicated her facial quirks and features. Much has been made of Kahlo’s “unibrow” and her facial hair, slight hints of a moustache or growth around the jawline. Despite her refusal to bleach or wax these parts of her body, fashion editors of the 1930s and early 1940s could not get enough of her striking looks and confidence. While she was in Paris in 1939, VOGUE magazine showcased her in the pages of their glossy, haute couture bible. She was a megastar: attracting attention for rebuffing what was expected of her by society standards.

VOGUE magazine featured Frida Kahlo in the pages of its magazine during her lifetime, circa 1939 (Courtesy of BBC America)

During her childhood, young Frida had contracted polio, which led to her having a noticeable limp. When she was 18 years old, and intending to become a medical doctor, she was involved in a horrific bus accident, which killed many of the other passengers on board. This accident caused her to have multiple broken bones, ribs, and pelvic damage. It resulted in her having to endure pain during her entire life; she’d attempt to overcome the daily agony through wearing a corset/back brace, having numerous surgeries, and eventually amputations of her toes and leg. It was said that Kahlo was always aware of her days being numbered, and therefore vowed to live each one to its fullest.

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, two artists who shared a complicated and lifelong connection

There are rather un-Barbie-like factors to Frida’s life, which make her selection as an Inspiring Woman à la Barbie rather eyebrow-raising. (Or unibrow-raising, I suppose, in this case.) Frida was an unapologetic Communist, was suspected of having inside knowledge of the assassination of Trotsky when he had fled to Mexico from Russia, and described American citizens as “boring and banal.” She was rumored to have had many female lovers, and publicly engaged in innumerable affairs while married to the more famous (at the time) muralist Diego Rivera. In addition to her damaged bones, ribs, spine, and pelvis, Frida also suffered from bouts of syphilis and other STDs. Again, these are rather amazing traits for a Mattel doll that was initially marketed to the 6-year-old and up set.

A portrait, done by Kahlo, of herself and her spouse, Diego Rivera. They were called “the elephant and the dove” by her father

I know that we often can’t judge our heroes by their private lives. The Founding Fathers are gods among men when they are examined for their constitutional and governmental achievements. When their one-on-one time with peers, spouses, children, workers, slaves, and underlings are introduced to the mix, these nearly divine men are found lacking. I think the same holds true for Frida Kahlo. Her work is a riotous burst of color and an exploration of a woman who was passionate about romance, her many loves, and her too-brief life. The whirlwind of controversy that billows about her reputation is the stuff of Hollywood biopics and tabloid rags.

Frida Kahlo used herself as a subject multiple times. She would combine her appearance with touches of the rain forest, wildlife, and unfurling tree roots and branches.

All artists seem to have grander appetites than “regular” people. It’s just shocking when it is applied to Frida, who was a petite and frail woman. In fact, when she married her husband, Diego Rivera, her parents were scandalized. Her beloved father said that it was like “an elephant bedding a dove.” Rivera was well known to be a womanizer (he had two common-law wives, simultaneously, before he legally married Frida), was celebrated for his romantic drive (he was a flatterer and a ladies’ man), a drinker and a carouser. These are two people who could lose themselves in their work for days and weeks at a time, and when they re-emerged, they would then throw themselves headlong into ill-fated and ill-advised infidelities.

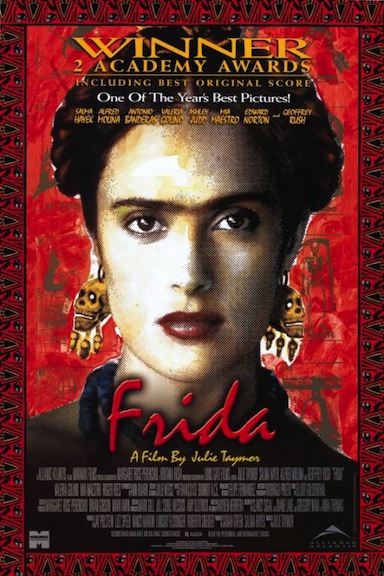

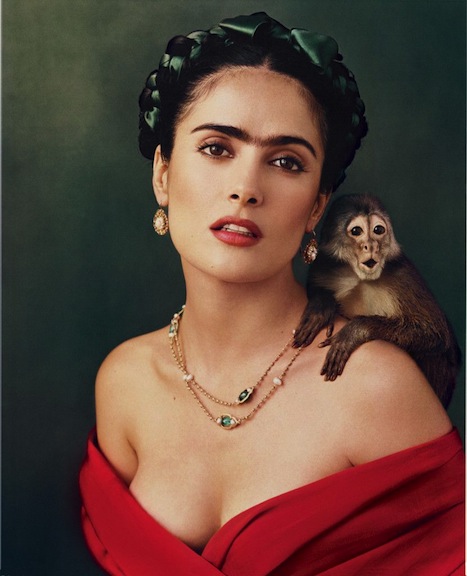

Salma Hayek produced and starred in the 2002 biopic of Kahlo’s life, “Frida”

The opportunity to play a woman who created brilliant, vivacious masterpieces, who loved frequently but not too wisely, who overcame pain and willed herself to create never-before-seen dream imagery, was irresistible for Salma Hayek. The Mexican actress co-produced the movie “Frida” with pre-disgraced Harvey Weinstein. She (naturally) gave herself the title role and hired theater visionary Julie Taymor to direct. The film garnered a 2003 Oscar nod for Hayek as Best Actress, which she lost to (an undeserving) Nicole Kidman for “The Hours.” The biopic was a personal pet project for Hayek, who wanted to bring the struggles and triumphs of a woman she admired to the big screen. She wanted to introduce this woman who embodied so much of Mexico’s pride and perseverance to the worldwide market.

Frida Kahlo has been hailed for her uncompromising look at her natural appearance (Courtesy of BBC America)

When Hayek learned earlier this year about the proposed Frida Kahlo Barbie doll, she was not pleased. And she was not silent with her disapproval. Hayek took to Instagram and Twitter to vocalize her annoyance, in both English and Spanish. She stated: “Frida Kahlo never tried to be or look like anyone else. She celebrated her uniqueness. How could they turn her into a Barbie? No puedo creer que hayan hecho una Barbie de nuestra Friducha que nunca trató de parecerse a nadie y siempre celebró su originalidad.”

Salma Hayek’s portrayal of Frida Kahlo included the artist’s compromised mobility and daily spinal afflictions (Courtesy of Lions Gate Films)

The actress/producer/activist ended her online comments with the hashtag #bodyimage. Hayek did not like the fact that the doll did not have the facial characteristics of the unibrow and slight moustache (though, in fairness, the doll’s eyebrows are much thicker and darker than what Barbie normally sports). She also took offense to the doll’s curvaceous proportions, height, lack of withered leg, and other physical differences that the doll did not exhibit.

Some critics pointed out that Salma Hayek was too glamorous to portray the frail, delicate invalid. (Courtesy of Vanity Fair)

It’s interesting to point out, however, that when Salma Hayek starred as the Mexican artist, she, too, was hit with these same accusations. Detractors said that she was too glamorous, too busty, too pretty, and too much a star to impersonate Frida’s frailty and seemingly down-to-earth humility. The very slights that Salma is now hurling at Barbie and Mattel were thrown at her back in 2001 when her movie began to receive press coverage, and in 2002 when it was released.

Full-length look at the sold-out Frida Kahlo doll from Barbie’s Inspiring Women series

Frida Kahlo has remained since her death in 1954, at age 47, an enigma that professors try to unravel in art history classes, that feminists attempt to unfold in college lecture series, and that authors continue to fight about in biographies and art analysis tomes. Some say she died from her body simply being exhausted, unable to battle anymore; her home attendant said she committed suicide, knowingly exceeding the maximum number of pain pills she was permitted. The specifics of her death are unknowable, as are so many other defining points of her life. Committed to a husband who routinely cheated on her, and to whom she did the same, Frida Kahlo was a difficult woman to understand.

Despite their tempestuous relationship, Kahlo remained tethered to Rivera through life. Show here: Kahlo’s “The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth, Mexico, Myself, Diego, and Senor Xolotl”

She has left behind her self-portrait canvases that give a hint to what she was thinking, feeling, experiencing, and dreaming about: her invitation for us to leap inside her head remains open and beckoning to all.