Photos Courtesy of Fox/HBO

The three women at the heart of the “Sharp Objects” murder mystery: Are they fragile, broken porcelain dolls?

Gillian Flynn is probably one of the most well-known, least-known, people in America. A writer of mysteries that always have a sinister, dark bent to them, Flynn is the author of the mega publishing blockbuster that became a world phenomenon motion picture, “Gone Girl.” However, like so many other authors, people tend to remember the titles of the work, and not the name of the talent behind it. HBO is currently airing a miniseries based on her first novel, “Sharp Objects,” and at the root of this chilling, serial-killer drama is a dollhouse, a dysfunctional family, and a desire to return to childhood, at any cost. In the milieu of “Sharp Objects,” women are often seen and expected to be porcelain dolls, but fragile dolls can become cracked and broken.

Missing posters and nighttime curfews pop up in the childhood hometown of investigative reporter Camille (Amy Adams).

The premise of “Sharp Objects” is a juicy one: a hard-drinking but introverted reporter returns to her hometown of Wind Gap, Missouri, to cover the murders and desecration of young pre-teen girls. The journalist Camille (played by Amy Adams) has a job where she is expected to dig into unsolved crimes and unearth hidden truths. Meanwhile, she hides away her own affliction: a covert and uncontrollable need to carve words into herself. Her body is a canvas of self-hatred, a written road map to her anxieties, fear, desperation, and conjectures about unresolved events of her past.

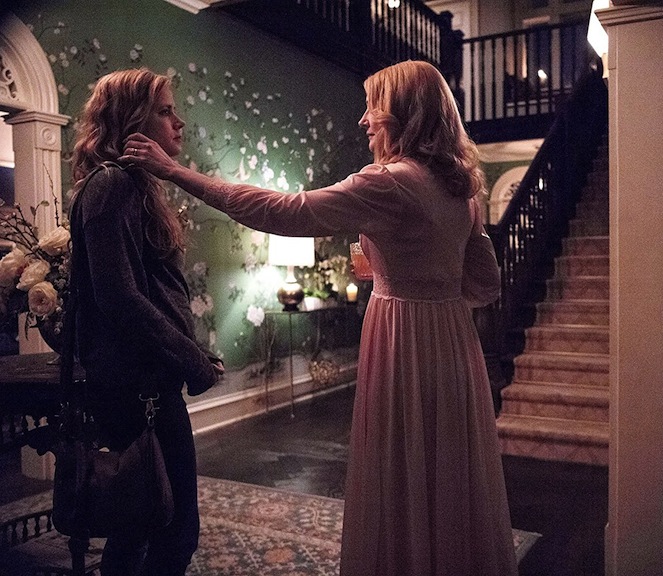

Patricia Clarkson as Adora, a seemingly selfless mother and nurturer

While cutting and doing self-harm has become a ritualistic pastime for Camille, her uptight and controlling mother (played by Patricia Clarkson) loses herself in community outreach and charitable endeavors. Named Adora, this family matriarch is not adored in the least by her eldest daughter. Camille resents her and has never resolved childhood issues surrounding the death of her little sister more than a decade earlier. Her sister was a sickly child, and she required the doting nursing of her mother. This bond between child and caretaker left no room for Camille.

The hometown of Wind Gap, filled with unspoken fears that bubble beneath the ice-cream storefronts

Returning to the stomping-grounds of her youth, Camille sees the dark corners of this town with grown-up, jaded-adult eyes. She begins to view her mother’s eccentric and supposedly selfless altruism with a suspicious mind-set. Camille’s deceased sister visits her in multiple ghostly flashbacks, and she works through these remembrances to see if they have any connections to the current deaths and disappearances of Wind Gap’s youngest girl citizens.

Eliza Scanlen as Amma, decked out in her handpicked little-girl garb

Among the new crop of social butterflies that flit around the town is Camille’s estranged half sister Amma (Eliza Scanlen). Like the other female members of Camille’s family, Amma appears to be living a double life. While wandering through the enormous Victorian home that the family resides in—ostensibly making them the wealthiest, most powerful folks in town—Amma dresses in the trappings of a little girl. Age 13, Amma allows her mother to choose her clothing, style her hair, and generally treat her like a dress-up doll. She looks like a 1940s or 1950s version of the perfect all-American girl. She’s not.

Amma is a rebel. Racing around town on roller skates, she leaves behind her dolls and her curated clothing.

The name “Amma” is “mama” rearranged, and she is her mother’s girl, for better or for worse. The huge mansion that they live in is both their shelter from the world outside—and also a conduit for unspeakable, unacceptable actions to occur. In this dominant house, where time seems to have stopped, mama Adora can re-live her loving, caring ministrations of her “perfect” dead daughter by coddling and cosseting the very alive Amma. She can play at having her deceased daughter magically resurrected by overseeing Amma’s every nuance and need. Amma’s bedroom is a sprawling concoction of pastel colors, bookshelves brimming with dolls, and expensive knickknacks artfully arranged. Adora is spoiling Amma, and in a Flynn novel, “spoiling” takes on its double meaning (to overindulge and to grow rotten and putrid).

Amma play-acting at being her mama’s perfect little daughter, dressed in an old-fashioned nightgown

Being her mama’s reflection and great unabashed love, Amma has a lot of mixed feelings. She displays her rebellion by roller-skating around town with a pack of adoring girlfriends. When she is out on the streets, she casts away the carefully chosen dresses, “Little House on the Prairie” nightgowns, and the meticulously arranged curls and ribbons. Outside of their mansion, she is no Shirley Temple or Barbie doll. Rather, she is every inch a Bratz doll, a rather racy and more seductive version of a tween who is on the cusp of her own sexuality! Amma plays at being the good girl when she is at home; when she races around Wind Gap, she is a hard-drinking, pill-popping nightmare. Only 13 years old, she plays at assuming the cynicism and world-weariness of someone twice her age.

Who doesn’t fit in back home at Wind Gap? A reporter investigates her own neuroses and suspicions.

“Sharp Objects” is a book and a miniseries that abounds with double meanings, double entendres, and demands to have double viewings. (If you watch it On Demand, and have a DVR, you’ll find yourself pausing and rewinding quite a few times to catch fleeting clues and crucial, hidden messages.) Among the multilayers is the connection between mother and daughters, and girls and society’s expectations for them. Just like Lena Dunham’s HBO comedy series “Girls” continued to be called that (no matter how close to 30 the characters became), “Sharp Objects” holds a looking-glass up to what it means to be a girl, and, more important, a “good girl.”

The dollhouse in “Sharp Objects” reflects the drama and the dreams of the dysfunctional family.

Within the Victorian mansion, Amma whiles away hours with a dollhouse that is a replica of her home. Each and every item is custom-made so that it approximates the décor and the furnishings of the house that contains her. But remember, this is a murder mystery, and the characters are all suspects. Returning to her childhood town and house, reporter Camille is expected to act as witness, chronicler, and maybe even detective. Within her home resides a woman she has doubts about (her mama) and a girl she has fears for (her sister Amma). The dollhouse is a physical tribute to the world that Amma is growing up in, and as Camille knows firsthand, the corridors and the hallways of their home are filled with unspoken truths and uncomfortable memories.

The ties that bind, and the memories that continue to haunt … “Sharp Objects” peels away a small town’s veneer.

Gillian Flynn constructed a multilayered mystery that revolves around a dollhouse, a girl who is seen as a living doll, and the connection that all women have to the toys and playthings of their past. Women can put aside the dolls that occupied their childhood days, but can they cast aside their juvenile ways?

Amy Adams might win an Emmy for her emoting in “Sharp Objects.”

That’s one of the sharp object lessons that this HBO miniseries captures and dissects. It’s a truth that viewers will be surprised to uncover, and a head-nodding denouement that we doll collectors and artists have come to expect. Once again, dolls are more than what they seem.