By Karen B. Kurtz

“History could be taught by means of dolls. The future historian will have no difficulty in reconstructing our age if she finds merely a few toys in dusty garrets or museums.”

— Laura Starr, “The Doll Book” (Outing Publishing, 1908)

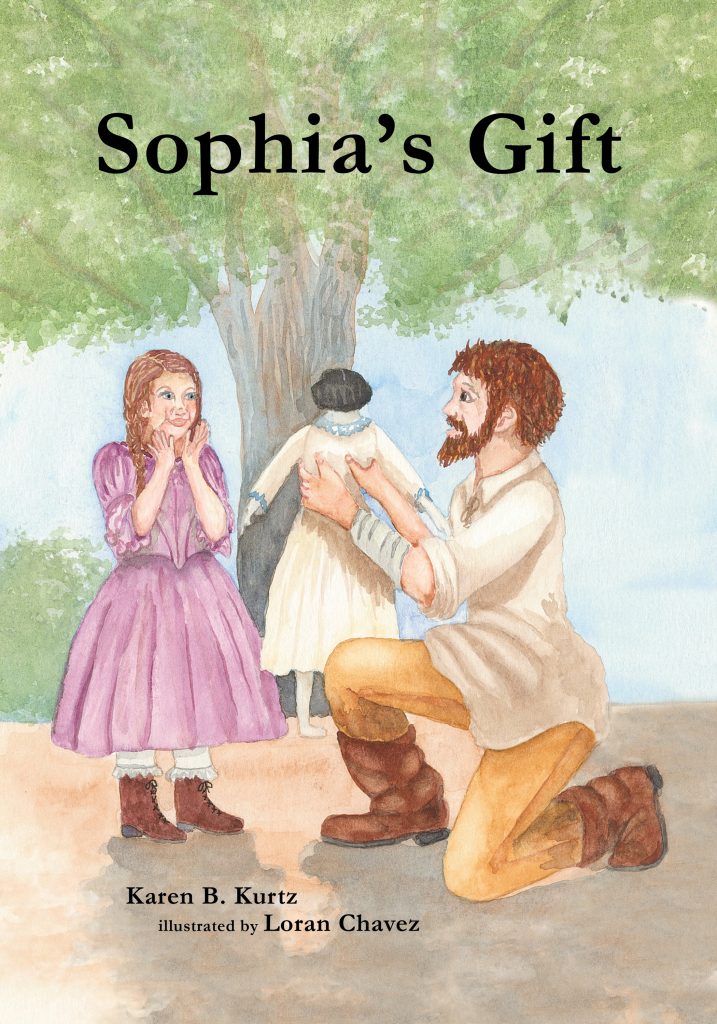

One of the projects that resulted from doll research that began over a decade ago came to fruition this year with the publication of my illustrated children’s book, “Sophia’s Gift.” Two months after the book was released, it won Gold in the 2021 Human Relations Indie Book Awards for cultural human relations in children’s books.

The journey of this book began in 2010, after I received the United Federation of Doll Clubs (UFDC) prestigious Coleman scholarship award to document true stories of American Civil War dolls with provenance. My photographer-husband, Mark, and I observed and documented scores of dolls across America and Canada that had been manufactured during that time. I also read original source materials and other documents to learn about the everyday lives of women and children from that era, including what they wore and what they loved.

We subsequently published about 30 articles in leading magazines and newspapers, including the UFDC’s Doll News, Antique Doll Collector, and Civil War Times. The Civil War Times commented on my work, “for the very first time, Karen speaks to the everyday lives of women and children, not men and battles.” This accolade put into words what I already sensed but could not articulate: that few books provide a glimpse into the daily life of women and children during the American Civil War, and fewer still talk about Jewish Confederates.

Meeting Grace Darling

We encountered the china doll Grace Darling in the vaults at The American Civil War Museum (acwm.org) in Richmond, Virginia. Grace Darling’s facial features were as bright as the day she left the German factory. Her original gown of black silk taffeta with broad purple and green stripes, though faded with age, was well-preserved. It still rustled when white-gloved hands tenderly adjusted it. Rose-point lace was beautifully handsewn to her collar and undersleeves. I knew at once that Grace Darling was extraordinary.

The doll’s provenance was detailed in a 1938 letter from Sophia Strauss Morris, who said a wounded Confederate soldier gave the doll to her in 1862 as a token of remembrance for helping to nurse him back to health. Sophia said she named her doll “after the English lighthouse keeper’s daughter.” After 76 years, Sophia gave Grace Darling and her letter of provenance to ACWM. She died soon afterward.

What child would name their doll Grace Darling? I wondered, intrigued. Most children of that time named dolls after an ancestor, like Ann B. Laws, or someone they knew, like Georgie Lott. What did “English lighthouse keeper’s daughter” mean? Staff at numerous libraries, museums, historical societies, and archives worldwide were eager to help me fill in the missing gaps.

The Lighthouse Keeper’s Daughter

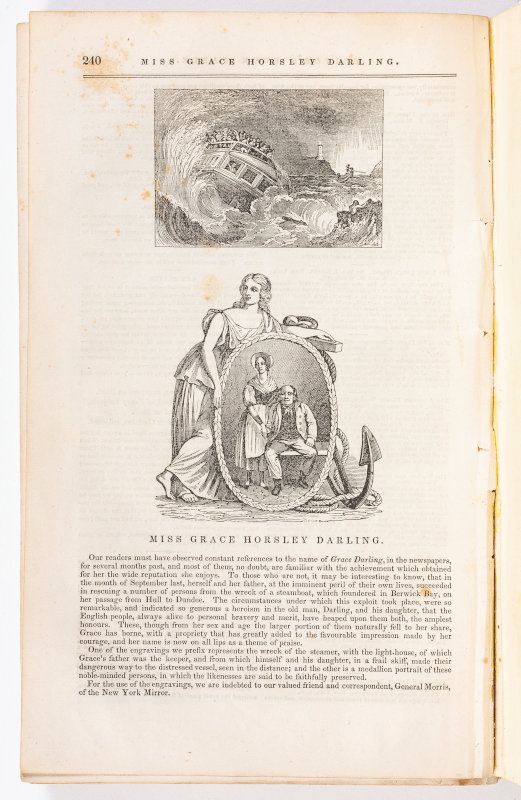

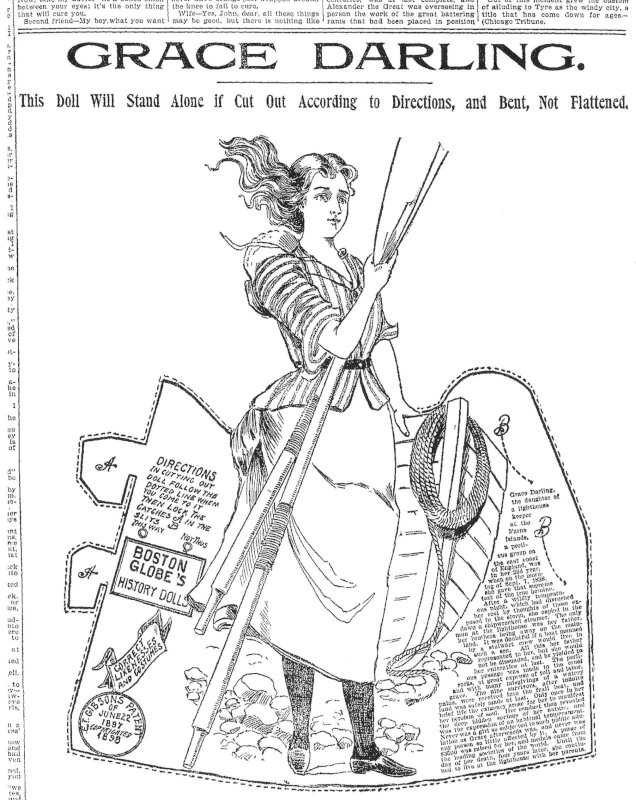

In the village of Bamburgh, on the rocky Northumberland coast in England, I learned about the real Grace Horsley Darling (1815-1842) and why Sophia named her doll after this British Victorian icon.

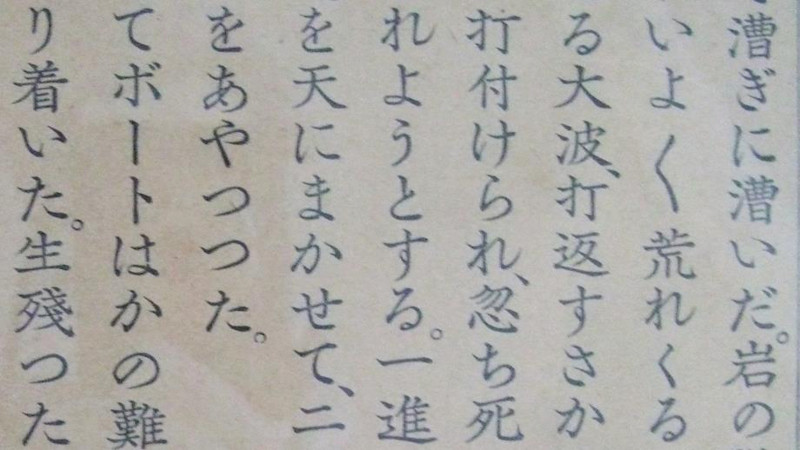

Grace was the daughter of lighthouse keeper William Darling, and grew up on a remote, bleak island off the rocky Northumberland Coast in England. In 1838, the steamship Forfarshire broke apart on jagged rocks during a brutal storm with 63 passengers and crew aboard. While keeping watch from the lighthouse, Grace saw the shipwreck and spotted people floundering in the water, fighting for their lives.

Despite the danger of the storm, she and her father rowed out to the rocks and managed to save the nine survivors of the shipwreck. The survivors spread the tale of their miraculous rescue, and the intensely shy Grace received most of the attention. The tale of her bravery made front-page news, even reaching Queen Victoria. Grace became a British media celebrity — William Wordsworth authored a poem about her, and artist Thomas Brooks made a painting of her rowing to the rescue.

Sadly, Grace succumbed to tuberculosis at age 27. After her death, her life story was transformed into a symbol of British courage and female virtue that resonated deeply with Victorian idealism. Grace’s story spread around the world and stirred imaginations for years afterward — just as Sophia Strauss was moved to name her beloved doll after the real Grace Horsley Darling.

Sophia’s Grace Darling

Alt, Beck & Gottschalck (ABG) manufactured the doll Grace Darling in the 1850s in the mountains near Stutzhaus, Germany. At 28 inches tall, Grace Darling was expensive in her time — a complete doll with china shoulder head, cloth body, and china limbs. She is recognized today by her “common” molded and painted jet-black Flat Top hairstyle — a term today’s collectors use to date dolls with similar hairstyles.

Sophia’s father, Leopold Strauss, was a Jewish immigrant from the German states, seeking a better life in America. He found work selling goods to farm wives in Virginia, grew prosperous, and established a general store in Culpeper, Virginia. He married Caroline Lowenthal in 1856 — the couple were the first Jews to settle in this small frontier town. Sophia was one of the couple’s 11 children. Townspeople called Leopold and Caroline “kind and generous,” saying Caroline “always found time to help others in need.”

Geography and circumstance made Culpeper a vortex during the Civil War. Located halfway between Washington, D.C. and Richmond, the town was linked by two railroads, plus the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers. Troops were always on the move, and more than 160 battles raged around Culpeper.

Experts believe the soldier mentioned in Sophia’s letter was wounded at the Battle of Cedar Mountain in August 1862, a battlefield eight miles from Sophia’s home. Everyone in town took in soldiers to nurse. No records were kept amid such chaos — Sophia’s soldier’s identity remains a mystery to this day.

During the war, when Leopold defended his store too zealously, Union soldiers ransacked it and hauled him off to a Washington prison, where he endured wretched conditions, including blindness. After the war, Leopold returned to Culpeper and managed to hang onto his store during Reconstruction’s challenging times. The Strauss family became a guiding force that helped Culpeper recover from the war.

Telling Grace’s Story

As I learned more about both Grace Darlings, along with the events and personalities from the past, I became determined to share the story. I drafted a chapter-book manuscript for middle-grade readers, but although the manuscript won several writing contests, I could not sell “Sophia’s Gift” to a traditional publisher.

I knew I needed to try something different. Eventually, I envisioned the work evolving from a middle-grade chapter book into a fast-paced, engaging read-aloud story for younger children. I created a 32-page picture-book dummy, storyboard, and a 500-word manuscript. Suggestions from Beta readers helped improve the manuscript’s clarity, story arc, and editing.

In the process of vetting numerous potential artists, I met the gifted Loran Chavez. Our personalities, thoughts, and passions meshed immediately, and we agreed to team up! Loran is fascinated by history, so research was the biggest part of her work. She spent hours looking for ways to make the story come alive in a believable 1860s environment. She also had to overcome the challenge of minimal models to portray the characters during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Meanwhile, I worked with micro-publisher Intellect Publishing to prepare “Sophia’s Gift” for print-on-demand publishing in both hardcover and eBook formats. Finally, I held the printed book in my hands this year, preserving this fascinating piece of history.

Find out more about Karen B. Kurtz at www.karenbkurtz.com

Autographed copies of “Sophia’s Gift” are available at sophiasgiftbook.com; the book is also available on Amazon and other major retailers.