At the beginning of the 20th century, destitute young Chinese women dressed carved wooden-head dolls in the costumes representing the various classes of people in their country. These dolls made at the Door of Hope Mission in Shanghai have captured the interest of doll collectors and are much sought after today. Like other pieces of Chinese art, these dolls have simple graceful lines and great attention has been given to the needlework in making their clothing. In the 19th century, foreign powers were trying to exploit China. Many European countries as well as Japan and Russia had been trying to separate China into spheres of influence and gain exclusive trading rights. The American interests wanted access to the country’s resources. This led to the famous “Boxer Rebellion.” The Chinese empress supported the “Boxer” uprising, which hoped to close China to all foreign influence. During this time anti-foreign feelings were directed at missionaries.

At the beginning of 1900 the “Fists of Righteous Harmony,” called by Westerners “Boxers” (because of their fighting techniques), attacked and slaughtered western missionaries and Chinese who had been converted to Christianity. Missionaries were forced to retreat to Shanghai for protection. Amid this backdrop of Chinese struggle for Confucian tradition and the resistance to entry to the modern world, some missionaries’ interest turned to the plight of Chinese women. Missionary women were shocked by the custom of early betrothal of young women, the binding of women’s feet, the kidnapping and slavery of girls and young women, the buying and selling of women as slaves and worse, as concubines and prostitutes, and the practice of killing unwanted female babies. Outraged by these conditions, five women of various Protestant backgrounds—an Episcopalian, a Baptist, a Methodist and a Presbyterian together with a China Mission woman—decided to open a mission to provide a safe haven for destitute young girls. These girls could not read or write; they had no skills. Shanghai police brought many girls to the mission. Girls as young as 5 years old were received there, and the mission also accepted young children who needed care.

The Door of Hope Mission first opened in 1901. A Protestant mission, it was not associated with any specific denomination and received little financial support from churches. Instead, it received its primary funding from charitable groups such as the Shanghai Rotary Club and the American Women’s Club, as well as the Shanghai Municipal Council and donations from residents of Shanghai. The Mission began in a single rented house but grew to include five separate “homes”—The Receiving Home, First Year Home, Industrial Home, Children’s Refuge, Love School and Hospital; here, anywhere from 125 to 200 girls were sheltered. Most girls stayed about two years, gaining self-esteem and skills that would make them self-supporting. Some chose to stay and help other girls; others went on to pursue their futures.

At the mission the girls were taught reading, writing and math, as well as personal hygiene. They learned to sew, embroider and knit. The first challenge was for each girl to make her own gee-ba, a Chinese garment, and then to make cloth shoes. In 1909, at the age of 17, Pearl Buck, daughter of Presbyterian missionaries and known to us as a prize-winning author, briefly volunteered as a teacher at the mission, instructing girls in knitting and embroidery. In 1910 Pearl entered the Randolph Macon Woman’s College. After graduating she returned to China where she spent most of her life and went on to write about Chinese life in novels such as The Good Earth, for which she won a Pulitzer Prize.

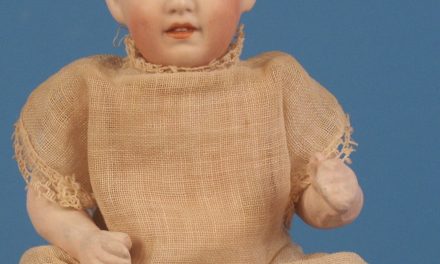

During their first year in the mission, young women were taught to dress the Door of Hope Mission dolls. They were paid for dressing the wooden dolls, but more importantly, in the process they also learned to appreciate and be proud of their Chinese heritage. The dolls were designed to be dressed in the traditional costumes of the Chinese people. The doll heads were carved of pear wood by local carvers and attached to cloth bodies, which were stuffed with cotton. Some dolls came with carved hands, others with no hands at all. After 1914, some of the dolls had feet or shoes of carved wood. The heads were simply painted with color added only to the hair, eyes, brows and lips. Since they were individually carved, no two are exactly alike; each head is unique. Their costumes were completely made by hand in tiny, carefully executed stitches. Most of the clothing could be removed, and the dolls were authentically dressed in white cotton underwear before adding the outer garments. The dolls measured 12 inches or more for an adult, around 8 inches for a child and 6½ inches for a baby or other small child. The early dolls are usually a little taller than their later counterparts. By most counts there are 25 recognized models representing a varied cross section of Chinese life.

Manufacture and sale of these dolls, as well as other knitted and embroidered articles of apparel and household goods, greatly contributed to the mission’s income and kept it open. In 1940 Kimport dolls, an importer of foreign dolls, advertised 20 various Door of Hope Dolls. When Chinese communists came into power in 1949, the Door of Hope Mission moved to Taipei and doll production declined.

The Chinese wore specific garments to maintain their cultural identity. Careful attention to their attire showed they were civilized. Various styles, fabrics and trims were prescribed according to age, gender and social status. Rank was exhibited by the cut, color and decoration-embellishing garments. Head wear, sashes and jewelry also signaled rank. Door of Hope dolls reveal these values. The 25 styles represented by these dolls are found dressed in variation using whatever fabrics were available to the girls. The dolls shown in this article were originally received through a missionary and were used in Cleveland, Ohio, for years by the owner to give talks to school children and other groups about China.

The dolls in this collection include the Bride, who wears the traditional red court dress with tassels. (Red, the color of life, was thought to bring happiness, good luck and wealth.) On her head is an ornate headdress with beads and tassels. She carries a red hankie edged in white. The Bridegroom’s purple silk coat has an embroidered square called a p’u-fang on both the front and back of his robe. Representing the Mandarin squares, these squares were worn by officials, a custom first practiced in the Ming Dynasty. The square, the symbol of the earth, historically represented his civil or military rank. Beneath the coat he wears the traditional brocade gown called a Ch’ang-fu.

A Young Lady is dressed in white (indicates purity, honesty and life) silk brocade robe with pink silk frog closures. Her straight hair is cut just below the ears. A Young Man wears a black brocade jacket, or ma-coual, over blue silk brocade Ch’ang-fu. On his head is a small black satin hat and on his feet black satin shoes.

A Young Lady is dressed in white (indicates purity, honesty and life) silk brocade robe with pink silk frog closures. Her straight hair is cut just below the ears. A Young Man wears a black brocade jacket, or ma-coual, over blue silk brocade Ch’ang-fu. On his head is a small black satin hat and on his feet black satin shoes.

An Old Lady has wrinkles carved in her face. She wears a deep-purple silk coat, or ma-coual, with frog closures over a long black skirt and purple pants. Her companion, the Old Man, is shown in a black ma-coual over a deep-blue Ch’ang-fu. Early dolls have a queue, long black braid in back, which was a style from the Manchu era when Han Chinese men were required to wear their hair this way.

Various dolls were dressed representing children. One Young Girl in silk, measuring 6½ inches, wears a pink silk jacket with green frog closures and green pants piped in pink. She has an elaborate decorative headdress which is worn over her long loose hair, as the custom was for young Chinese girls to wear their hair flowing until they became adults. A Boy, 8½ inches tall, wears a fancy gray brocade silk jacket with full sleeves and pink brocade gown. Other children, dressed in cotton, are referred to as “schoolgirls” and “schoolboys” while yet another youngster is referred to as the “Kindergarten child.”

Amah is the nurse that carries a baby on her back. She wears a simple cotton jacket over pants, the attire of the working class. The costume is completed with a black hat (not shown) and black silk shoes. In contrast, she carries a Baby in a silk pouch on her back. The Baby wears a pink silk print costume and headdress with tassels.

The Mourner is dressed for his father’s funeral. Three cotton balls are on his hat to catch his tears, and a paper wand in his right hand serves to drive off evil spirits. He is dressed in coarse hemp fabric; this unbleached fabric signifies the simplicity and austerity of the Mourner. The Widow wears a sack-cloth costume of hemp and a long brim covering her face to conceal her grief.

Representing various occupations, a Shanghai Policeman is attired in a dark-blue uniform with gold buttons and braid. A large tan hat shades him from the sun. A Farmer is dressed to work in the rice fields. He wears a simple blue cotton suit under a straw raincoat and a woven coolie hat. He is barefoot (carved wood feet). Peasants and other members of the working class wore cotton garments. A Buddhist Priest wears a muted yellow robe with frog closures down the right side and matching shoes; a small black hat covers his shaved head.

The Manchu Woman is dressed in an elegant pink satin robe trimmed with soft green frog closures on the right shoulder. All traditional garments fasten on the right, never on the left. It is considered uncivilized to fasten garments on the left. Green binding is also at the edge of her sleeves and the bottom of her robe. She has a carved wooden headdress, which as been painted. Her feet have been carved of wood to represent shoes with platforms on the bottom. (Manchurian women did not bind their feet.) China is a country with deep traditions. Door of Hope dolls help us to understand and appreciate these people and their culture.