There’s an old, familiar saying: “A penny for your thoughts,” which implies a person is deep in meditation, conjuring up bright ideas, lost in a world of her own. Switch the spelling of “penny” to “Peni,” and you’ve got the perfect profile of Canadian artist Peni Dyer.

Born in Jamaica in 1942, the talented sculptor has a landscape filled with imaginative creations cavorting in her mind. She is always ready to explore the fantastical figures and real-life inspirations that swirl in her thoughts.

The artist describes her childhood on a sugar cane plantation as “fairly isolated.” She and her sister were often left to their own devices, which meant they developed an enormous capacity for pretending and playing make-believe.

“I would describe my family as quiet and joyful. My parents divorced when I was about 5 years old, and my mother moved back to Kingston with my brother. So there was just my sister and I, and then my father remarried. We delighted in our stepmother! She believed children should be allowed to be children as long as possible. When we came home for the holidays from boarding school, we ran wild and free on an enormous property.”

years old, and my mother moved back to Kingston with my brother. So there was just my sister and I, and then my father remarried. We delighted in our stepmother! She believed children should be allowed to be children as long as possible. When we came home for the holidays from boarding school, we ran wild and free on an enormous property.”

Dyer’s stepmother was a social worker who earned the Order of Jamaica for her contributions to the community. Dyer’s father was the timekeeper, or foreman/manager, of the plantation where they lived. “He had to hire just the right amount of people, supervise their labor at planting time and crop time and during the growing season. He also had to keep account of their hours of work and pay them accordingly.”

Having a stepmom who was free-spirited and indulgent, coupled with a practical, business-minded dad, helped cultivate Dyer’s personality. She is a creative soul who well understands the financial demands and restrictions of a career in art. She knows that it is a rare individual who is truly able to support herself by following an artistic goal.

As a teenager, Dyer began to realize she had ability and talent in painting and drawing, skills that came easily to her. “When my sister and I were told we were ‘too old to be playing with dolls,’ I then spent most of my free time drawing and painting. With all that practice, I would almost always win the end-of-the-year art prize for my age group.”

When it came time to choose a profession, Dyer lobbied her parents to allow her to study art. “My father would have preferred if I had pursued my early dreams of becoming a veterinarian because he was convinced that all artists ‘die poor.’ My stepmother felt I had the right to follow my dreams of becoming an artist. Little did I know back then what that would entail. I did have their full support, however, when I decided to go to Canada to study art there.”

Emigrating from the warm, sultry island of Jamaica to the “great white north” presented an eye-opening experience for the young teen—people are essentially alike around the world.

Emigrating from the warm, sultry island of Jamaica to the “great white north” presented an eye-opening experience for the young teen—people are essentially alike around the world.

“When I first came to Canada, I was 17,” Dyer recalls. “I wasn’t affected by cultural differences, for the people were very friendly. Apart from having a different accent, they weren’t all that different from people in my hometown. I did have to learn how to deal with the long, cold winters. And perhaps my biggest adjustment was learning to adapt to the bulky clothing to ward off the cold.”

While the weather may have been frigid, Dyer’s pursuit of learning and living was heating up. “I completed a three-year degree in commercial art. In my third year, I did sculpting with a live model for one semester, but I didn’t get a good grade. I had spent most of my time flirting with a young man in my class and never finished my project. I would never have believed I would end up being a sculptor.”

After graduation, “no one would hire me, the ‘great artist.’ I finally found a job with an interior design firm. In addition to clerical and reception duties, I was given the opportunity to work in the design studio and make mock-ups or presentation boards.”

Dyer kept this job for nine years and then returned to Jamaica, where she worked as a personal assistant to a minister of government. She loved the job, but began to mourn the lack of artistic challenges. Eventually, she returned to Canada in 1980 and went back to the same firm she had left in 1971. “I spent the next 16 years working in that job until the company was downsized, and I was out of a job in 1996.”

It was around that time that Dyer tried her hand at dollmaking. Initially, she made a dollhouse family from a kit for a friend who had purchased an enormous doll house. “All I had to do was paint the faces and fit the limbs to the cloth bodies, but she was so impressed and delighted she asked me to make her a fairy doll.” Dyer declined, claiming she wasn’t a dollmaker. “When my friend purchased a porcelain fairy doll from the United States and told me what she had paid for it, the challenge loomed for me to try making one.”

The aspiring doll artist signed up for lessons in china painting, and, after a year of painting dolls from commercial molds, she tried sculpting her own.

“I had the unique ability to capture the likenesses of my subjects. It didn’t take long before I started getting commissions for portrait dolls of children,” she confides.

Today, the busy doll artist juggles her sculpting with her teaching of the fine points of portraiture and porcelain modeling. Her calendar is filled with requests to do commissioned work: dolls based on photographs of children and celebrities. She also finds the time, though, to pursue subjects close to her heart.

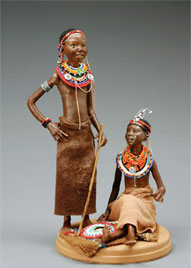

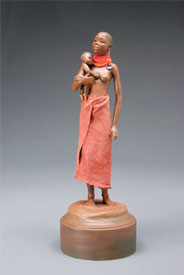

“I started doing figures of the Maasai people two years ago. I feel a profound kinship with these beautiful, creative, earthy people,” Dyer explains. “Their whole way of life is being swallowed up by industrialization and that saddens me. I intend to add one or two pieces to the series every year.”

In addition to her African tributes, Dyer would like to sculpt likenesses of personal heroes, such as Mother Teresa, Nelson Mandela, Albert Einstein, and Bob Marley, among others.

At her side as she loves, laughs and labors is her soul mate, Michael, her partner of 25 years. “I had an unsuccessful marriage for 10 years, but I now live with Michael. Between us, we have six children and 11 grandchildren. Michael is my engineer. He has the unique ability to figure out the most complicated mold, make me any base or prop, and he always loads up the van and drives us to any doll show no matter where it is.”

Dyer’s thoughts these days are happy and productive. Her peace of mind and devotion to her doll craft is golden. “Dollmaking is food for the soul to me,” she affirms. That sense of satisfaction is priceless, far beyond pennies.

Peni Dyer, 83 Morrison Crescent, Unionville, Ontario, Canada L3R 9K7; telephone: (905) 477-4267; Web site: www.thelivingdoll.net; e-mail: penid2000@hotmail.com