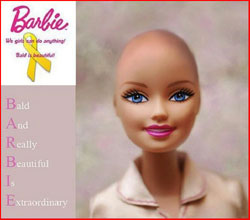

Amy van Boxel’s Sabita. All photos courtesy of Amy van Boxel

Now that we are officially in the upswing of the holiday season — radio stations are sprinkling Christmas tunes into their playlists — we all have certain songs that we look forward to hearing more than others. I admit I like all the old familiar standards — the Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and Doris Day crooners can make me tear up as I listen to them crisply enunciate the themes. (The lyrics from “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” particularly slay me: “Through the years, we all will be together — if the Fates allow . . . “) It’s a rare Noel opus that talks so beautifully and poignantly about future celebrations where revelers may no longer be around to attend. It makes you appreciate every day with one another, doesn’t it?

That’s why it’s so meaningful to me to look through the archived photos and interviews I’ve conducted with talented artists over the past years. One of the extraordinary women I had the pleasure to chat with is Dutch doll maker Amy van Boxel. The daughter of the pioneering artist Bets van Boxel, Amy joined her mother’s creative team in 1996, making this year her 20th anniversary in the doll realm. I think this is a perfect time to reflect on what Amy shared with me because her multicultural dolls truly mirror the spirit of the Christmas season.

(Rouro, depicting a child of Panama)

If you’re a fan of Yuletide music, you probably know the haunting melody of the Trans-Siberian Orchestra’s instrumental classic “Christmas Eve/Sarajevo 12/24.” The song was released in October 1996 — so it, too, is celebrating its 20th anniversary — and it focuses on the ravages of war. According to the story behind the song, it musically tells the tale of a cellist, Vedran Smajlovic, who returns to his hometown of Sarajevo, only to discover it in total ruins after the nation’s devastating civil war. As Sarajevo continues to be bombed and shelled — neighbor against neighbor — the residents flee to underground shelters. That is, everyone but the returned musician. Instead, Smajlovic marches to the town square, where a fountain and library once stood, and climbs atop the rubble with his cello. As the sky lights up with the aftermath of war, he plays Christmas music among the smoking debris. After the Siege of Sarajevo had ended, the musician was tracked down by a reporter and was asked why he would put his life at risk by performing nightly in a vulnerable war zone. The cellist answered it was to prove that the spirit of humanity existed, despite all evidence to the contrary.

(Angelina, also from Panama)

That acknowledgment of shared humanity is at the heart of Amy van Boxel’s beautifully crafted child dolls. So often, people are quick to pre-judge (hence, the word “prejudice”) and make wide, ridiculous assumptions about “different” people and other cultures. Amy’s dolls reveal the shared innocence, wonder, and purity of children the world over. Her dolls, which are garbed in realistic renderings of traditional costumes and wardrobes, are goodwill ambassadors for preaching the need to do good and to be good.

“Every doll shows the love that I put into it as I made it,” Amy told me. “When collectors choose to buy my creations and then bring it into their homes, I find that to be the highest compliment. It makes me so happy that I could work with my mother for so many years and learn from her. It is because of the collectors that we were able to make these children and share their beauty worldwide.”

(North Vietnam’s Sabita)

Just as a photographer frames and captures a revelatory shot, Amy is able to freeze a particular moment in time, transferring a mood and emotion into her doll canvas. A world traveler, she would have her creativity and curiosity piqued when she visited and explored brand-new locales. For instance, during her time in Vietnam, Amy was inspired to conjure up the very lovely “Sabita” rendering.

“‘Sabita’ belongs to the Black Hmong tribe. She hails from Sapa, North Vietnam. On her back, she carries a basket with hay. The authentic hat and jacket are originals. I bought them myself from a nice lady from the Hmong tribe when I visited Vietnam with my family a few years ago,” Amy recalled.

(Panamanian Kaya, showing off a traditional form of body paint)

The same attention to detail, and determination to get it “right,” was seen in her tribute to Panama’s young residents. “Kaya’s body was originally painted with indelible black dye made from Jagua fruit in the ancient traditional way. The painting is for beauty, but it also acts as a natural insect repellent and has anti-infectious properties,” she explained. “Villagers alternate between traditional dress and western clothes. I always strive to be respectful of their culture.”

One of the lessons that Amy learned, and it bears repeating, is that so many cultures and their traditions seem disparate upon first glance, but a closer inspection shows how they have many similarities. She definitely discovered this, and put it to good effect, with her blending of African and Asian parallels.

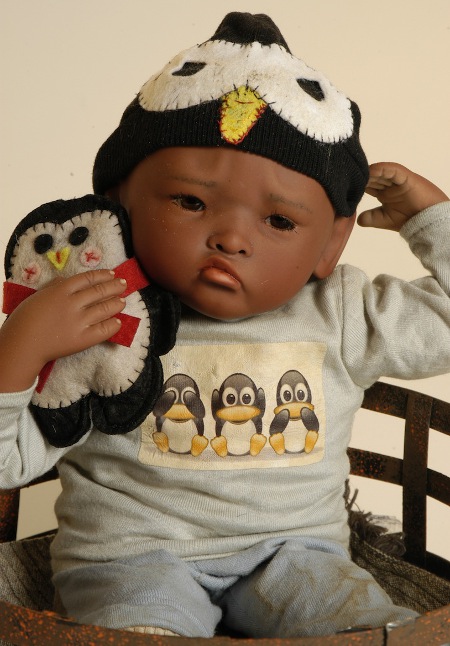

(Van Boxel’s “See No Evil” babies, Kike, Miro, and Damare, have names inspired by Japanese “See No Evil” figures.)

“There are ancient statues found in Japan and in Africa that represent the phrase ‘See no evil, Speak no evil, Hear no evil.’ This is such a well-known phrase and it is found in both of these cultures. That really inspired and touched me,” Amy wrote. “When I made the dolls, I gave them African complexions, but their names are similar to the Japanese names of the figurines.”

It is a lovely way to bring attention to the commonality of the world’s vast continents, countries, and cultures. During the run-up to December 25 — the day where Christians the world over honor the birth of the “Prince of Peace” — it is humbling to take stock of the fact that there are many people on the planet who do not practice that faith or live by that calendar’s date. That should not diminish the importance of Christmas — whether it is celebrated religiously or with a more secular overtone — but it should make many of us consider the words to the Christmas fund-raising single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”

(Close-up photos of Damare, above, and Kike)

Recorded four times in the past 32 years (1984, 1989, 2004, 2014), it elevates the notion of Christmas as more than just a day of frenzied gift-giving and holiday celebrating. It makes concrete the notion that there are other nations that need help and assistance year-round, and perhaps in the Christmas spirit, revellers can share a prayer, a thought, and a donation. I think Amy van Boxel would be proud to think her dolls coax the same global outreach and concern:

It’s Christmastime; there’s no need to be afraid

At Christmastime, we let in light and we banish shade

And in our world of plenty we can spread a smile of joy

Throw your arms around the world at Christmastime

(Amy van Boxel of De Poppenstee)