(“Imitation of Life,” made in 1959, and surprisingly relevant today? Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

The Academy Awards are going to be broadcast on February 26, 2017, and one can only imagine the level of forward-thinking fashions, political barbs (subtle and not-so-subtle), and cultural surrealism that will be swirling about during the 89th annual orgy of opulence! It’s sort of impressive that the Oscars are a year shy of 90. Rather than sliding into the comfort of becoming a precious, revered institution, the award ceremony always struggles to remain relevant, current, and reflective of what’s happening on the pop-culture front lines.

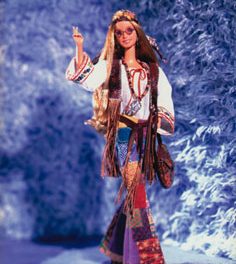

(Blue Goddess is an evocative Gene doll that channels Lana Turner and other TCM stars. Photo courtesy of Ashton-Drake Galleries)

Keying into the run-up to the big day, Turner Classic Movies (TCM) has been showing a potpourri of flicks that have won or had been nominated for tons of Oscars in the past. The 31 Days of Oscar programming is fun for film buffs, but it’s also food for thought for doll connoisseurs, too. I’ve been feasting on the array of movies that have dolls and plush animals decorating the sets, becoming a tacit commentary on who the characters are and what the worlds are about to evolve — or devolve — into. I’ve also been in seventh heaven with seeing how many of the classic Edith Head wardrobe designs, Oleg Cassini gowns, and Jean Louis costumes were honored by the Gene dolls.

(Dressed by Jean Louis, Lana Turner, one of Hollywood’s screen goddesses, emotes as Lora Meredith. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

There is one filmmaker who has never met a fashion doll or a baby doll that he didn’t want to incorporate into his cinematic settings. Sure, there are tons of producers and directors who have utilized dolls (and I’ve discussed them in past blogs), but for this outing, I want to chat about Douglas Sirk and his celluloid collectables. They figure heavily in many of his offerings, from robots and animatronics to dollhouses and frilly French porcelain bébés.

(Douglas Sirk, the lionized director in his later years. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

Sirk has been celebrated as the king of the “woman’s picture,” meaning his projects focused on female protagonists — often reaching across class lines and racial divides — and discussions of what a woman’s role was meant to be in middle-class and upper-middle-class environments. For instance, a typical Sirk-helmed script would present a recently widowed woman, who was smart, attractive, and still desiring love, but was expected to retire into a future of being a doting mother-in-law, grandmother, and eventual burden to her family. Sirk would dig in and discuss: What if the woman was only in her late thirties or early forties? What if she’s still sexually attractive, with a libido that is healthy and a wish to act upon it? How should these women act when the dollhouse planning from their childhoods haven’t panned out as they expected?

(“There’s Always Tomorrow” explores the “illicit” relationship between a fashion maven and a toy manufacturer. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

In many of his movies, dolls are seen in the background and in the foreground. They are the outlets for many of his young characters’ frustrations and ambitions, hopes and fears. The dolls of Douglas Sirk act as the mouthpieces of his young girls, and as signposts for the movie viewers.

In 1959’s “Imitation of Life,” which is shown a lot on TCM, the lovely widow Lora Meredith (played by Lana Turner) befriends an impoverished black woman, Annie Johnson (played by Juanita Moore), and her daughter, Sarah Jane. What’s fascinating about this scenario is that the friendship quickly — almost instantaneously — becomes an arrangement of an employer and a domestic. Annie immediately volunteers to make the meals, wash Lora’s stockings, and mind Lora’s daughter, Susie, in exchange for staying at Lora’s apartment. Struggling to become a model and an actress, Lora accepts the situation. She pays lip service to the awkwardness of having a maid — without being able to compensate Annie for her services — but she definitely adapts to the setup quite quickly and easily.

(A new family arrangement? Or a working relationship, with the women falling into their racially expected roles? Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

One of the fascinating points that Sirk delves into is the nature of race. The actress Lana Turner is pale and blond, cool and aloof. Her daughter, Susie, is traced from kindergarten age to late teens, where she is then portrayed by Sandra Dee. The two women seem to be physical mirror images of one another, but the audience knows that Susie is much more the daughter of the devoted and selfless housekeeper Annie. While Lora/Lana has pushed herself to climb to the pinnacle of Broadway and movies, she’s left her daughter in the care of a selfless and noble woman, her taken-for-granted confidante/servant.

(Lana Turner and Sandra Dee portray a mother and daughter who can’t see eye to eye. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

Audience members see how kind and nurturing Annie is. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the contemporary Caucasian moviegoers must have recognized how motherly Annie is, but her skin tone relegated her to a housekeeper that one would like to employ — not a woman that one would aspire to be. Annie’s dark skin, which is noticeable in connection to actresses Lana and Sandra, is the impediment for her own personal happiness in the movie. Her late husband had been a light-skinned black man, and her daughter, Sarah Jane, is even lighter than he was. Sarah Jane fawns over Lora and Susie — wanting to be like them. When she sees her skin, and compares it to her mother’s, she is angry, embarrassed, and resentful.

(The Gene Incognito doll reflects Lana Turner on the set, looking incognito – see photo below. Photo courtesy of Ashton-Drake Galleries)

(Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

The first night that Annie and Sarah Jane camp out at their new abode, considerate Susie offers one of her dolls to Sarah Jane. Interestingly, Lora must be a progressive mom, because among her daughter’s toy chest is a black baby doll. Susie offers the dark-skinned doll to her new friend, and is greeted with outright hostility. Sarah Jane seizes Susie’s blond, white doll — that is what she wants to nurture. That is what she wants to be. When Annie talks her daughter into relinquishing the white baby doll and accepting the black one, Sarah Jane is inconsolable. Before she heads to bed, she throws the black doll to the ground. The camera lingers on it lying there, alone and unloved.

(Sarah Jane rejects a black baby doll. She refuses to accept her racial identity. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

This is the core of the movie: Why does the complexion of a woman determine her path to success, happiness, love, and life? Sarah Jane does not want her African-American heritage to be known. She spends her life trying “to pass,” and by doing so, sends messages of shame and hostility to her mother. As we watch the Lora character ascend to stardom, despite beginning her quest at a relatively late age, we see how the grown-up Sarah Jane (played by Susan Kohner) careens from one seedy chorus job to another. She desires a life as an entertainer, a leading lady, but her “blackness” prevents that. Even though she only looks like a Caucasian woman with a tan, her “blood” betrays her. It is a roadblock to any professional or personal satisfaction. It is also a weapon she uses to browbeat and demean her mom.

(Sarah Jane, fighting to pass for white, dances in front of white masks, foreshadowing the tragedy of her life. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

If you haven’t seen “Imitation of Life” — there are two classic versions, 1934 and 1959 — I urge you to search for it. The 1959 Lana Turner version is the one that I would suggest because it is much more sympathetic and more aware of the imbalance of power between the two leads. Turner’s Lora and Juanita Moore’s Annie are both widowed women, both having to fight for economic security, both having to raise a child. For Lora — like all of the other onscreen counterparts who had shiny hair, straight teeth, cute figures, and white skin — her life would involve chasing her dreams, catching some, abdicating others. But regardless of how high she climbed, or how low her spirits would plummet, she was on a movie star’s journey to joy. Was there ever a moment when the viewer didn’t know Lana Turner would land the right guy and have a shot at wedded bliss?

(John Gavin and Lana Turner have their spats, but they are destined for one another. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

Douglas Sirk concentrates a lot on the flip side of happiness. He gives Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner, playing the estranged mother and daughter, all the best scenes. They have the dramatic showdowns; they have the revelatory monologues. Though Lana Turner was the big, bankable name that the studio was hanging their investment upon, it was Moore and Kohner who grabbed Oscar nominations. Neither woman won, but Kohner did earn two Golden Globes (Best Newcomer, Best Supporting Actress) for her complicated and self-loathing portrayal.

(Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner are trapped by what society sees them as. Photo courtesy of Movie Star News)

It’s an odd experience to watch this movie in 2017, but the undertone of a divided nation, a culture that values some appearances over others, some backgrounds more than others, has not receded into the past. This movie is antiquated and anachronistic in many ways — thank God — but it is also extremely observant and enduring in how it dissects privilege, social expectations, and class distinctions. That’s quite a lot for a “woman’s picture.”