Hayley Mills, with doll, in Disney’s “Pollyanna.” It’s deeper than you think!

Photos courtesy of Movie Star News

Available on Netflix and Amazon, as well as popping up now and again on Turner Classic Movies On Demand, “Pollyanna” is a film that most people think they know, but truly do they? I mean, if I were to say the title to you, don’t you instantly think about a super-sweet, sickeningly wholesome movie about a Goody Two-shoes who runs around smiling stupidly and grinning vapidly? I know that for many of us in the jaded 2000s, the movie definitely has that association of being sappy Disney, a cavalcade of too much good cheer, too much cheese, and too much Technicolor. If that’s what you think about this flick, then you are in for a fierce surprise.

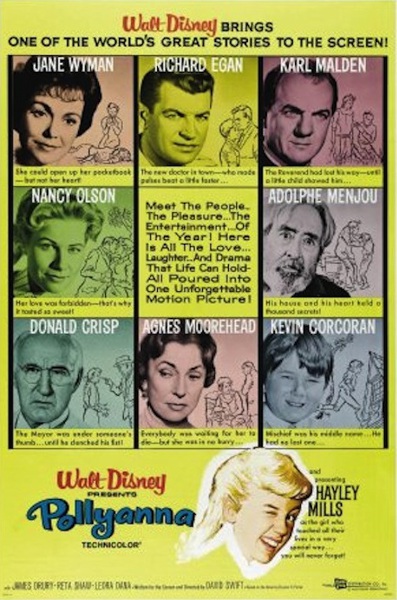

The movie poster shows off the damaged residents of the town who are saved by Pollyanna.

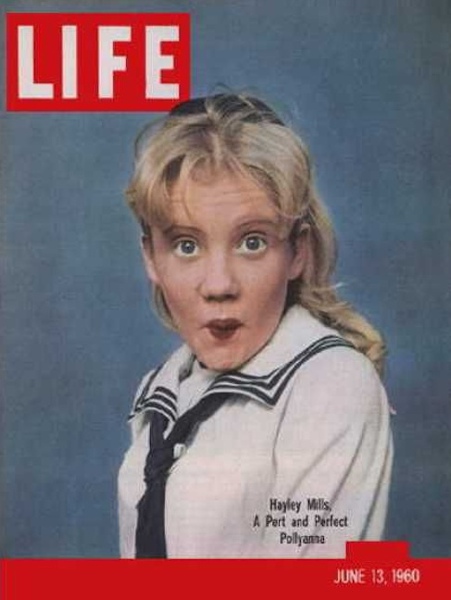

Made in 1960 as a vehicle to introduce Hayley Mills to American audiences — she was already part of the legendary Mills acting family back in England — “Pollyanna” was the perfect way to launch the 14-year-old’s stellar movie career. It is indeed a film that focuses on happiness and the basic need to share love, and spread good karma wherever one roams, but it also has a darker, more mature context to it. The 12-year-old Pollyanna character isn’t a mindless, joyful simp — a spoiled little rich girl who has a bright silver spoon and enjoys shining it. No, she’s an orphan who has been sent to live with her cold, aloof aunt Polly (played by Jane Wyman, the first Mrs. Ronald Reagan). The headstrong niece has to contend with a deep cultural rift between the proper, well-to-do world of Main Street and her own unbridled background as a free-spirited, nature-loving daughter of an impoverished missionary.

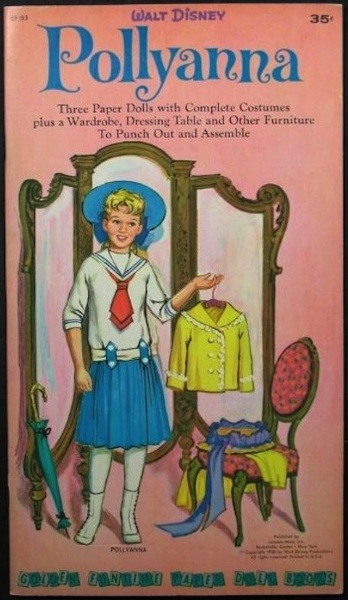

The Golden Book cover focuses on the tie between Pollyanna and her wished-for doll.

Yes, Pollyanna does seem to have an unsinkable, buoyant nature, but we learn that it is something she has been taught to do. She and her father had always engaged in the Glad Game — a manic pastime of listing what there is to be happy about, despite all evidence pointing to the contrary. And, of course, a doll — or the lack of one — is at the root of this psychological defense mechanism.

Pollyanna embracing the doll on the book’s title page.

In a very hard-to-pull-off performance, young Mills explains to the viewers that one of the things she most yearned for was a doll. However, because she and her family were living in such financially difficult conditions in the West Indies, they had no money set aside for any personal luxuries. They depended on the kindness of strangers — and the movie viscerally demonstrates that there is a difference between charitable obligations (like giving down-on-their-luck neighbors jars of unwanted calf-foot jelly) and really doing good works (visiting and encouraging shut-ins and invalids).

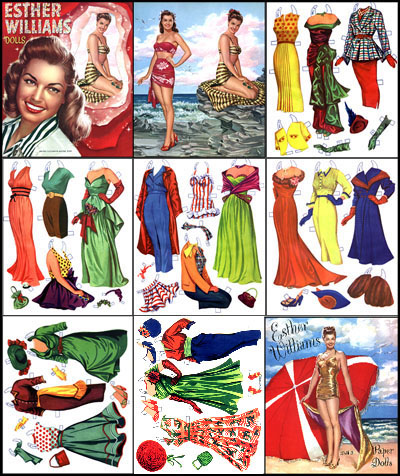

Pollyanna’s paper doll book gave her a wide array of clothing and accessories.

In Pollyanna’s Caribbean experience, her family always received cast-off clothing that was ill-fitting, and their household necessities allowed her to exist, but not really thrive. When her father tells her to go ahead and ask for a doll to be donated, she does so, and her hopes are dashed. Rather than getting a doll, she receives a pair of crutches. Now, for most people, the aspect of living in everyday hardship — toyless, ill fed, not well dressed, hardworking — would be a difficult reality to endure. The mix-up of crutches versus a doll (I still can’t figure out how THAT happened) would send most mortals over the edge. But Pollyanna and her dad engage in the Glad Game: “What is there to be glad about now, daughter? You don’t have a doll.” “Dad, I have crutches, but I am glad I don’t need crutches!” (Remember this exchange, because it’s going to come back and haunt poor Pollyanna later.)

You see, nothing can keep this girl down. However, seething beneath a perennially optimistic disposition, Pollyanna does have her own self-absorbed and mercenary side. While at a carnival, an extravaganza designed to turn the tide of the town against her aunt’s omnipotent political and financial clout — yep, this is not the “Pollyanna” you remember — the spirited youngster engages in a game of prize fishing.

Julie Good-Kruger’s version of Pollyanna and the prize-fishing event.

Because she’s done so much to elevate the moods of her new neighbors — gave faith and courage back to the minister who had become her aunt’s mouthpiece at the pulpit; introduced a poor orphan to a wealthy hermit who was in need of a companion; restored vitality to a hypochondriac who preferred to lie in bed all day and shop for coffin hardware and casket lining — when Pollyanna tries her luck at hooking a prize, the game is rigged in her favor. Rather than reeling in a rubber duck or a peashooter or some frivolous piece of junk, Pollyanna pulls out a doll — a beautiful doll that even matches the fabric of the dress she’s wearing!

Pollyanna collectible doll made by Uneeda.

But Pollyanna has been living a dual life. Yes, she is conducting herself as a dutiful niece to her coldhearted but complicated aunt — a woman who is incapable of exhibiting love because she might be fearful of being rejected or perhaps she’s afraid of being humbled and knocked off her perch. However, Pollyanna is also part of the “resistance” against her aunt and her aunt’s control over every aspect of the townspeople’s existences. (Aunt Polly is like a Mafia don in a high-neck Edwardian gown. She oversees banking, industry, the newspaper/media, the church, charities, and social etiquette. If Aunt Polly doesn’t approve of what you’re thinking, wave your thought good-bye. She’s a formidable, yet well-mannered, despot. She is beyond Big Brother; she’s Big Aunt.)

Pollyanna discovering rainbow prisms with the town’s secretly rich hermit.

Pollyanna has thrown in her lot with the lower classes: the recluses, the orphans, the misunderstood; the economically downtrodden, the working stiffs, the domestics, the forgotten and the put-upon. Pick your preferred revolutionary of the moment, and put him or her in a pleated pinafore. That’s how Pollyanna behaves.

Dealing with a hypochondriac sourpuss, Pollyanna convinces the woman to make a quilt for the “let’s revolt against Aunt Polly” carnival.

She knowingly has joined forces with the entire town to supplant her aunt’s pulling of the purse strings. Aunt Polly apparently places family legacy over the safety of orphans, and refuses to build a new house to accommodate the many children who reside in the unstable, unfit institution. She wants to keep the old edifice in tact because it belonged to her family; she doesn’t want to have her past razed.

Pollyanna in peril! Her bravado has her out on a limb.

So, Pollyanna, flush with the victory of winning her prized doll, has to sneak back into her room. She has escaped by scaling down a wizened old tree, and now she has to make her way up that same menacing trunk. Making it even more dangerous than the journey down, Pollyanna has her brand-new doll to worry about. Keeping it in her mouth, and not daring to look down, Pollyanna begins her midnight climb up the perilous tree. It’s obvious to us at home that this is not going to end well. The girl is placing too much emphasis on a material object.

The doll is placed on the roof …

Placing the doll on the steeped mansion roof, it appears that it might fall to the ground. Not wanting to lose the one possession she has ever coveted, Pollyanna makes a mad grab for the doll, and loses her balance. Back in the early days, Disney movies never shied away from heaping abuse on their characters — think “Old Yeller” and “Bambi” — and Pollyanna is no exception. She was always able to bounce back from adversity, but even she cannot survive a plunge from an old oak tree.

Pollyanna falls out of the tree, and is seriously hurt.

Lying on the ground, bent and limp like a rag doll, the aftermath of Pollyanna’s fall is difficult to witness. The one thing to be glad about — hey, Pollyanna would want me to play the game — it wakes her aunt up from how horrible she’s been to the town residents. Polly Harrington might have a town named for her, but her niece Pollyanna has the people of Harrington Town in her heart. Miraculously, the doll has survived the tumble — not even a crack in its head — but Pollyanna is paralyzed.

LIFE magazine recognized that this was a star turn for Hayley Mills.

Yes, this is a Disney movie. This is a Disney movie from the studio where the animated mother of a deer got killed by buckshot, and young boys were forced to shoot their dogs that were showing signs of distemper. It was a different world 57 years ago, and that is what is so fascinating. A movie like “Pollyanna” could not be made today. It would take a tough producer to cripple the main child heroine, and have a positive spin on it. Additionally, Pollyanna traffics in third-rail political behavior: She resurrects religiosity within a pastor who has lost his way; he had grown too dependent on Aunt Polly’s hardnosed view of the world and her tithing. She interferes with a maid’s love life, inspiring her to get married, stop working, and begin a family of her own. She even brings romance into her aunt’s lonely life — having her aunt realize that controlling a town is no match for being a wife and a mother. For all her revolutionary ways, Pollyanna spreads the insurrection of good, old-fashioned American societal values. It’s a conceit that couldn’t get funded today. Pollyanna and her spunk topple the social order of that town, and it becomes the kind of bygone, nostalgic burg that Disney World’s Main Street replicates. With her British accent and stiff upper lip, Hayley Mills’s Pollyanna ironically stages a mini Americana Revolution.

The movie really is a square-off between two single-minded females: Aunt Polly and Pollyanna.

Pollyanna seizes the town’s fortune (and misfortune) away from her steely aunt and places it into the hands of the town elders. (Mind you, women don’t have the right to vote during the time of this movie, so it’s the misters who will be running Harrington from now on.) The movie ends with Pollyanna, unable to walk, and Aunt Polly heading by train to Baltimore, where she will undergo an operation to reverse her injury. I can only hope that in 14 years or so when women have the vote, Pollyanna will run for public office on a well-thought-out platform.

Pollyanna and her doll wave good-bye, leaving the small, needy town behind.

The final scene is a picture-perfect framing of Pollyanna, Aunt Polly, and the doll as they look at the townspeople who have poured out to wave farewell at the station. I am overjoyed that Pollyanna has her doll — she suffered for it. But I have to think she might have been more glad to have those crutches.