Photos of Mary Astor courtesy of Movie Star News

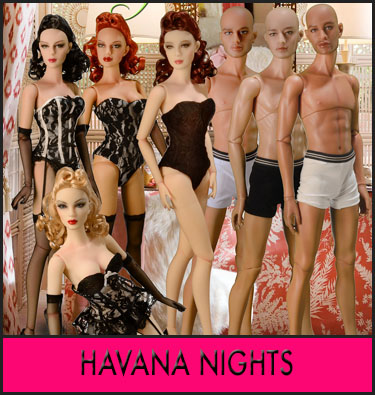

A visit to the Tonner Doll Company booth at Toy Fair is always a worthwhile stop. This year’s showcase was small on quantity — were there just about a dozen dolls on hand? — but definitely large on quality. There was also an invisible thread that connected three of the dolls that were highlighted on the artist’s display counter.

In 2017, Robert Tonner chose to make two portrait tributes of a revered actress whose name is recognizable, but who isn’t as adored as, say, Greta Garbo or Jean Harlow. To TCM fans, Mary Astor is known as an actress of great reliability, fresh good looks, and cinematic versatility. In “The Maltese Falcon,” she does a slow burn as a film noir femme fatale. In “Meet Me in St. Louis” and 1949’s “Little Women,” she’s the embodiment of the patient, caring, devoted, prim and proper mom.

Mary Astor was a glamorous and aloof actress.

Portraying classy women, with an undercurrent of sensuality, or upper-middle-class matriarchs with well-bred elegance and patrician bearings, Astor always delivered a performance that seemed technically spot-on and was pleasant to watch. She didn’t sizzle like contemporaries Marlene Dietrich, Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Crawford, or Bette Davis, but Mary Astor acted competently and professionally enough to win an Oscar in 1941 for “The Great Lie.”

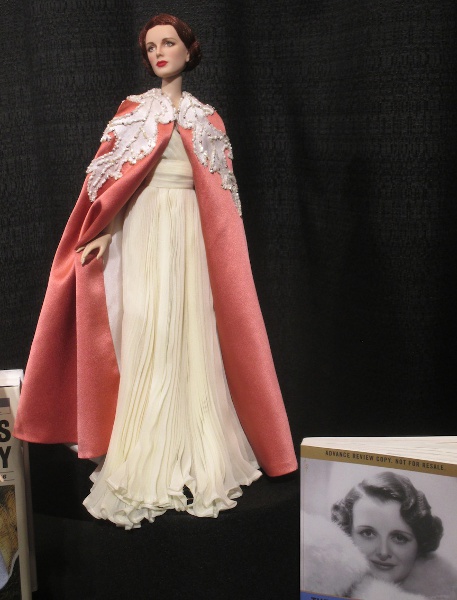

Tonner’s Astor doll in cape is a regal and elegant creation.

The term “lie” is perfect for the real-life goings-on of Mary Astor. Her celluloid persona was nearly upended and then destroyed by her private activities. A woman who was in full control of her libido and sexual impulses, Astor was not a shrinking violet. She saw a man that she liked, and she courted him. Married four times, Astor was not shy about the “boudoir,” and she was known (off-screen) for indulging in numerous love affairs. It was rumored that as a teenager she had a passionate fling with theatrical and film luminary John Barrymore, who was 24 years her senior. (She was 17, and he was 41.) Celebrated for her icy, glacial beauty, she attracted many Hollywood hunks who all wanted to see if they could melt her cool exterior.

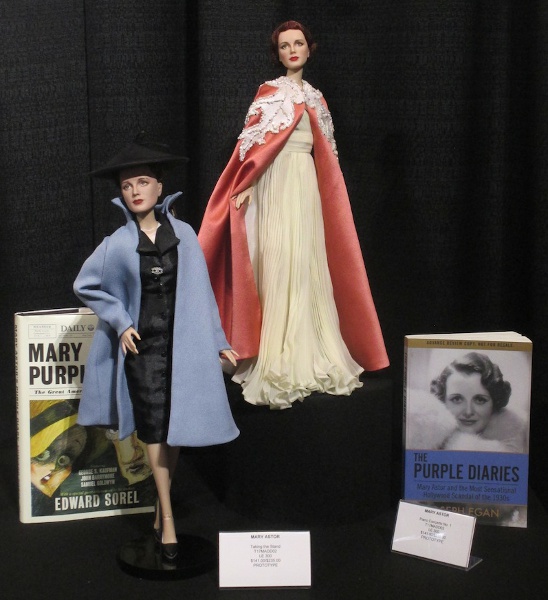

The Mary Astor dolls were posed next to this year’s diary publications.

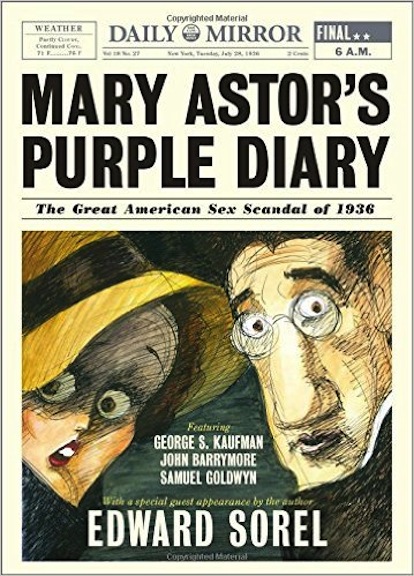

Astor’s interior life was anything but cold. She proved this with her private diary that meticulously chronicled her romantic interludes. This year, two books have been published that reveal the impact that Astor’s tell-all journal had on her career and her reputation. She painstakingly recorded every moan, shriek, and cry of ecstasy that she shared with her married lover George S. Kaufman. Kaufman is one of Broadway’s most honored playwrights and directors. He won Tony Awards and Pulitzer Prizes; “You Can’t Take It With You” and “Of Thee I Sing” were two of his big, blockbuster hits. Kaufman was not known for his movie-star looks or physique. Rather, he was feted for his intellect, wit, and dramatic clout.

The comely, shapely actress and the charismatic, cerebral author met and sparks flew. They engaged in a tempestuous love affair that was a not-so-secret secret. Everyone in their inner circles knew about it, and Kaufman was notorious for always bedding the most attractive women in his shows and in other producers’ venues. In fact, the bespectacled playwright was jokingly called “Public Lover Number One.”

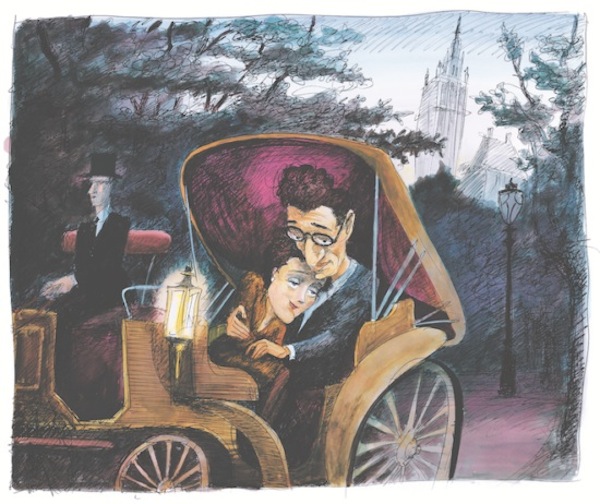

Mary and George in a horse-drawn carriage, an illustration from the Edward Sorel book.

During their nearly daily coupling, both Astor and Kaufman had spouses back at home. When Astor’s husband, Dr. Franklin Thorpe, discovered that he was being cuckolded, he divorced her in 1935. (Kaufman’s wife turned a blind eye, racking it up to the old “boys will be boys” alibi.) The following year, in 1936, Astor’s explicit diary was mentioned in court as potential ammunition. Her husband’s legal team was determined to use it against her in custody proceedings. They wanted to prove that any woman who engaged in such heated bedroom behavior was not fit to be a mother and should be kept away from her own children.

Literally becoming part of her “trial and tribulations,” excerpts from Astor’s “purple diary” (“purple” meant it was scandalous and erotic) was fired at her to prove she was an unfit mother. Her sexuality, which was always repressed on the screen and just hinted at, was in full bloom in her actual life. Astor feared that the 1936 trial would make her box-office poison. In the pre-World War II years, women in films were very much viewed in the “madonna” or the “whore” camp. There was no mixing of those two components. Onscreen good girls remained virginal and untouched; naughty girls were world travelers and adventurous.

The judge who presided over the custody trial eventually ruled that the diary could not be considered as evidence. It had been stolen from her desk, and Astor insisted that some of the most lascivious passages that had been referenced were forgeries. She and her attorney insisted that the most outlandish escapades were made up by her husband and his lawyer. The diary was then ruled to have been “mutilated and manipulated.” Judge Goodwin J. Knight ordered it sealed and impounded. The “purple diary” was taken to a bank vault and locked away, not to be seen or discussed, until this year, it seems.

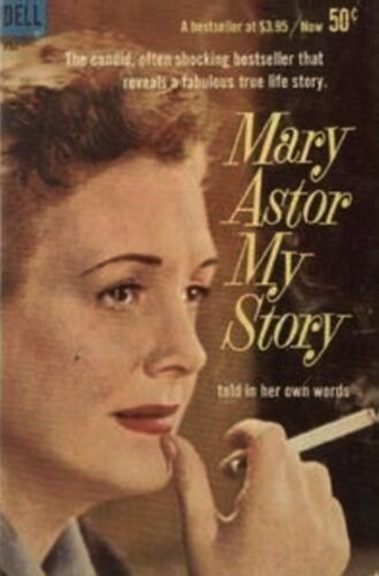

Mary Astor cashed in on her press by eventually writing her own story.

With the world changing and Europe going on fire with the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, social norms were breaking down and falling away. The public had been tantalized by Astor’s exploits, and they were shocked to see that an actress, who had nary a hair out of place on the big screen, could have been a “wildcat” in her off-hours. Rather than her career being derailed, Astor’s next movie, post-trial, became an enormous hit. “Dodsworth” emerged as one of her biggest moneymakers. The audience wanted to come out in droves and see exactly what they hadn’t noticed before in the cool and reserved Astor.

Eighty years after all of these fireworks have fizzled away, Tonner’s two dolls key into the insanity that surrounded a married woman discussing her pre-marital and her extramarital affairs. The public knew that Hollywood stars lived by a different ethical code; divorces were common among that set. Astor’s “crime” was that she wasn’t the wronged party. Rather than sitting at home, weeping and knitting while she was made the patsy by a caddish husband, Mary Astor was a powerful woman who caroused, drank, gambled, and pursued a larger-than-life existence. She was bigger than the parts she played.

Two nonfiction books are available now that trace her hectic, chaotic life and times. These books were next to the Astor dolls, and so was another doll, which is a descendant of the Astor Hollywood glamour and sexuality. “Kadira” was sculpted by Robert Tonner and designed by Andrew Yang. Yang is the grandson of Mary Astor, and he couldn’t be prouder that his grandmother has been enshrined as a Tonner heroine.

Andrew Yang at Tonner’s Toy Fair 2017 booth.

While Astor had to button up for the movies she made — like I said, she was all about a repressed celluloid sexuality or a ladylike allure — Yang’s doll collaboration with Tonner is 100 percent va-va-va-voom. The doll is a roadmap of curves, mountain peaks, and more curves. “Kadira” has a head of flowing, cascading blond hair — practically platinum — and her bosoms are not covered up or draped in any way. If Mary Astor was all about having to live a double life — a tribute to repression and societal conformity on film; a follower of her heart and her hormones during her downtime — then the Yang doll is the yin to her yang.

The Kadira doll leaves nothing to the imagination.

There is no repression in this doll. She embodies a sexualized and sexy, fierce diva. She has it, and she flaunts it. Mary Astor didn’t have permission to be herself in the public arena. The world hadn’t yet become that permissive. Who knows how she would have fared today? Would any of Astor’s behaviors even been termed “antics” or “escapades”? Would she just be another Hollywood actress who seems to have an uncanny knack for choosing the wrong man at the wrong time?

The cover of Edward Sorel’s book says it all!

It’s impossible to know for sure, but 2017 seems to be the right time for rediscovering this actress and realizing how her performances were so different from her actual self. And that is the height of great acting.