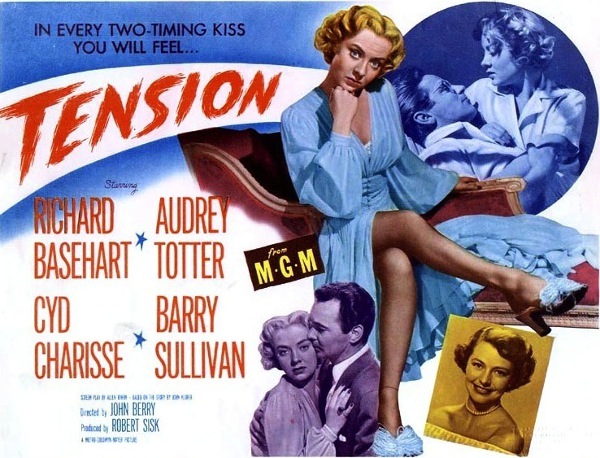

This “Tension” poster says it all. Two-timing abounds!

Photos courtesy of Movie Star News

What is it about 1940s and 1950s crime dramas and dolls? Besides featuring “broads” who are nicknamed “dolls,” “dollface,” and “dollies,” these hardboiled molls frequently come with actual playthings: namely boudoir and/or porcelain dolls. Back in the 1920s, these very same dolls, designed for adult women, became must-have collectibles: a celebrated sign of female independence and purchasing power. Fast-forward 20 years, and the notion of a liberated woman was seen as downright scary. (And so were her glazed-over dolls!)

This connection between dangerous dames and the dolls they love is incredibly showcased in the 1949 film noir cult classic “Tension.” The flick stars Richard Basehart, who plays a restrained and mild-mannered pharmacist; Audrey Totter, embodying a selfish, promiscuous, two-timing wife; Cyd Charisse as the sweet and nurturing girl next door; and Barry Sullivan as the wise and wisecracking homicide detective who is going to tie all the loose ends together.

Set in post World War II America, “Tension” doesn’t just show off the panic and fear associated with a murder (plotting it, trying to carry it out, worrying about being caught) but it really showcases the undercurrent of tension that existed between returning war veterans and the women who had to readjust to their male counterparts’ arrival and assimilation back home.

Audrey Totter looks as sultry as any Gene doll, doesn’t she?

Just think about it: while husbands, brothers, boyfriends, fathers, and all manner of male citizens had been overseas in the military, women were left at home, in many cases ruling and raising their households. The expression “wearing the pants in the family” hits home in the 1940s and 1950s when women, more and more frequently, were garbing themselves in this traditionally male getup. In “Tension,” we see this friction played out with the two leading ladies wearing pants, but with totally different attitudes.

Audrey Totter is the wife who has forgotten her vows and is living for her own pleasure. She has a scenery-chewing showdown with Basehart as her milquetoast hubby. They are both wearing high-waisted pants and Totter looks like she could take Basehart, crack him over her knee, and then head out to devour a dinner of raw hamburgers and a hunk of pie with whipped cream. (Pharmacy lunch counters play a big role in the movie, and we see Totter and her love/hate relationship with food.)

Wearing pants and a black shirt, Audrey tells off her husband with huge bossy bravado.

Cyd Charisse also wears pants, and she is first seen in the movie decked out in pants that are rolled up to expose her pretty, dainty calves. Best of all, while in these pants, she is seen hanging off a ladder, with her legs spread so far apart she could be mistaken for Gumby or a very bendable Barbie. That doll connection is extremely important because Charisse’s character, Mary, makes a little doll memento of herself that she gifts to Basehart as their warm romance develops. It is a very simple concoction created from pipe cleaners (I recall) and thus can be handled and reshaped by its owner. In other words, it can be bent by a man.

Cyd Charisse is shown from the legs up, with her pretty legs still in plain view.

Totter’s doll, on the other hand, is a large porcelain beauty. It is often seen lounging on the unhappy couple’s bed, holding court in the boudoir, lying there expressionless and cold. That sums up Audrey’s personality in a visual nutshell — at least in relation to her pharmacist husband. Totter’s character is called Claire, and that is an intentionally ironic name. There is nothing clear or bright about her disposition — that is, if you take “bright” to mean sunshiny or upbeat or luminescent. If you look at “bright” as smart and clever, Claire is certainly that. In fact, with her eventual comeuppance, she proves that she is too smart for her own good.

Wanting more out of life than a little house with its own washer-and-dryer, which is what Basehart promises her, Claire trolls moviehouses, bars, and popular nightspots, seeking male attention. She is not above removing her wedding band if it will help her land a guy’s affection and interest. In a film noir, she is bad news, but her hubby, character name Warren Quimby, can’t get enough of reading the devastating headlines she constantly hands him. He is her sucker; she is his downfall.

Claire’s doll has much in common with her petulant owner.

Throughout the movie, the camera lingers a lot on Claire’s face as she is constantly judging her husband and finding him lacking. She regards him as such a foolish, boring patsy that she abandons him to try her hand at finding the American dream with a big, boisterous liquor salesman. Like I said, Claire is too smart for her own good. If she found life with a mouse of a man to be unbearable, how would she cope with a guy who is immeasurably more macho and domineering?

As a film noir, there are tons of twists and turns, and Claire’s porcelain doll is there to witness all of them. The fragile plaything does suffer a good-size chunk of damage, and its pretty face is wrecked. This echoes Claire’s own fate: her pretty-as-a-picture life is going to be upended, too. Dolls are a great way for film directors to get their point across instantly, and the doll here does that quite well.

The doll’s crackup will mirror Claire’s own fate.

Audrey Totter, who died in 2013 at the age of 95, was pretty much the pinup “bad girl” in film noir capers. She personified the woman who had no regard for the damage she would callously leave in her wake. With every step she takes, and every room she enters, a plaintive sax orchestration follows her undulating moves. Her stock in trade was playing women who epitomized sexual demands, sexual appetites, and sexual favors. In 1949, her self-interest and self-pleasure were to be feared and snuffed out.

Her boudoir doll, which would have been a symbol of sophistication two decades earlier, is shown here as a glimpse into her stilted psychological state. She is not able to be maternal and nurturing, like good neighbor–good girl Mary. Instead, she is all about self-aggrandizement and self-satisfaction, like a child. The doll is her crutch; it shows the audience that she is still trapped in this world of playing. For Claire, she is playing with objects and playing with emotions.

Richard Basehart’s character has his crucial epiphany while holding Claire’s doll.

Luckily, for old-movie fans, I am pretty sure Turner Classic Movies will be airing this flick in mid August. Their schedule can change due to programming fluctuations, but August 14 is when it is set to broadcast. You should definitely check their listings and see. If you have a DVR, program it to catch this psychological whodunit and whydidtheydoit.

“Tension” is a terrific film because it has a fun plot where there are double crosses, double switches, and the male protagonist (Basehart) even gets to play double characters: upstanding Warren Quimby and his alter ego, Paul Sothern. It also has a very insightful glimpse into the archetype/expectation of females in films and in real life as well. Audrey Totter is the blond glamour-puss, but she is broken and damaged beneath her porcelain complexion. Cyd Charisse is dark-haired and slim-hipped and dewy-eyed. She is wholesome and fresh-faced and speaks with the clipped accent of a woman recently graduated from a finishing school. She would make the ideal spouse for a junior executive on the rise. Audrey Totter’s Claire, on the other hand, wears bullet bras that turn her shape into a lethal one. Whenever she is caught in profile, she is all hard edges and built like a weapon!

Good girl Mary and her mirror opposite, bad girl Claire.

Enjoy this movie for its use of wardrobe (note how the color black factors in Totter’s outfits) and see how free-living, free-spending, free-loving women were the enemies or, at least, the threats in these post–World War II screenplays. Women had their time to play while the men were away. When Johnny came marching home, women were expected to be in the kitchen, waiting for them, cooking for them, and obeying them.

Audrey Totter plays a woman who has heard it all and seen it all. She tunes out her hubby.

Playtime was over; wife time was here — whether a hard-bitten dame liked it or not. Audrey Totter’s character is the poster child for a woman whose spirit had to be broken, and Claire’s doll has the battle scars to prove that!