A rose is a rose is a rose, but a doll is not always a doll. At least, that’s the guiding force behind the photos of Chinese poet and artist Liu Xia. In a society like ours, where every person with a keyboard and a camera phone can become an Internet gadfly—I’m looking in the mirror here—it’s difficult to imagine a culture where access to television, radio, the Web, and public discourse is denied daily. In fact, it’s beyond being denied—it’s squelched, squashed, and declared “a crime against the state.”

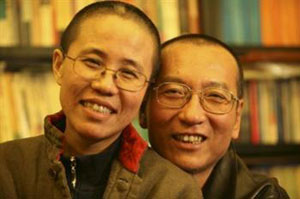

I’m not writing about some sort of fictional, alternate reality—like Suzanne Collins’s THE HUNGER GAMES—I’m referencing China, a country that holds familial ties to me. One of the People’s Republic’s most famous dissidents is Nobel Peace Prize–winner Liu Xiaobo, who was recognized with the award in 2010. A professor and a public reformer for a democratic China, Xiaobo had been arrested in 2009 for his vocal and tireless agitating, and was sentenced to more than a decade of confinement.

been arrested in 2009 for his vocal and tireless agitating, and was sentenced to more than a decade of confinement.

While behind bars, he was given the honor of the Nobel Peace Prize, and his wife, Liu Xia, was immediately put under house arrest, where she still remains. And that is why her doll photos are so amazing and so chilling.

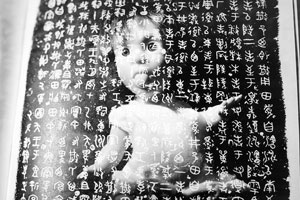

Xia utilizes dolls, which she calls “ugly babies,” as props to represent the way the Chinese people are denied freedom and access to education, public discourse, and personal choices. Among her compositions is a pairing of a doll perched on the shoulder of her husband before his most recent incarceration: it is a testament to how all citizens of China can have their strings pulled—their fates cradled in the hands of others. They are left feeling impotent—needing to cry out and feeling afraid and alone.

A friend of the couple, Guy Sorman, who is a French economist and writer, visited Xia in her Beijing home in 2010. He saw the black-and-white photos, which she shot and developed in her personal dark room, and urged her to show them publicly. Knowing that she could not do so in her homeland, Xia agreed to allow Sorman to take the pictures out of China and give them a public viewing elsewhere. The photos have cropped up in Europe, America, and in other countries where democracies are functioning and flourishing.

A friend of the couple, Guy Sorman, who is a French economist and writer, visited Xia in her Beijing home in 2010. He saw the black-and-white photos, which she shot and developed in her personal dark room, and urged her to show them publicly. Knowing that she could not do so in her homeland, Xia agreed to allow Sorman to take the pictures out of China and give them a public viewing elsewhere. The photos have cropped up in Europe, America, and in other countries where democracies are functioning and flourishing.

The pictures are large—measuring 3 x 3 feet. They couldn’t be simply carried inside a person’s valise or backpack without raising eyebrows at customs. So, Sorman took a couple of prints, and then convinced other visitors to Xia’s house to “smuggle out” the remaining ones. There are 26 photos in all, and each person agreed to ferry one to freedom. The transporting and traveling of the images took over a year.

person’s valise or backpack without raising eyebrows at customs. So, Sorman took a couple of prints, and then convinced other visitors to Xia’s house to “smuggle out” the remaining ones. There are 26 photos in all, and each person agreed to ferry one to freedom. The transporting and traveling of the images took over a year.

The doll photos, which Sorman is the curator of, are packaged under the gallery name “The Silent Strength of Liu Xia,” and they were at Columbia University for a few weeks. (The show closed on Thursday, March 1.) It is now heading to other locations, which Liu Xia is willfully ignorant of.

The doll photos, which Sorman is the curator of, are packaged under the gallery name “The Silent Strength of Liu Xia,” and they were at Columbia University for a few weeks. (The show closed on Thursday, March 1.) It is now heading to other locations, which Liu Xia is willfully ignorant of.

And that adds an additional heartbreaking aspect to this tale of dissent, underground exhibitions, and friendship that promotes political rallying. In order to protect herself and to be able to truthfully tell the government that she has no idea of the showings and its itinerary, Xia requested that she be kept entirely in the dark. She has no knowledge of when her photos are being showcased; where they are being mounted; and who is attending and commenting on it.

When a person is lucky enough to see this show as it wends its way around the world, he or she is striking a blow for personal expression. I found out about it as it heads toward its final American date in New York City (April 20, at press time), and was able to catch the installation (http://www.italianacademy.columbia.edu/).

Dolls have long been used as a metaphor in artist showings: creative types from Degas and Dahli to Beth B and even Gloria Vanderbilt have utilized dolls and doll parts to make a point and move an audience.

For Liu Xia, who finds herself confined in her home, these doll photos are eerily personal and prophetic. She took the series of photos back in the late 1990s, utilizing dolls that she had received as gifts from a friend in Brazil. At the time, she never imagined that she would find herself imprisoned in her house 15 years later. Just as a doll is placed in its dollhouse, and told what to wear, how to behave, and what to do by its owner, Xia is now locked away and given her daily marching orders by the ruling party.

back in the late 1990s, utilizing dolls that she had received as gifts from a friend in Brazil. At the time, she never imagined that she would find herself imprisoned in her house 15 years later. Just as a doll is placed in its dollhouse, and told what to wear, how to behave, and what to do by its owner, Xia is now locked away and given her daily marching orders by the ruling party.

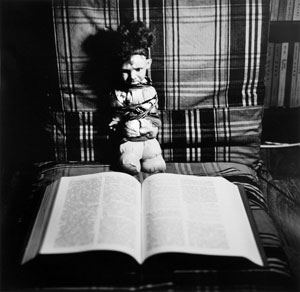

Books and writing tools, bindings and blindfolds, suffocating plastic bags and crucifix-shaped wooden poles, play pivotal roles in her artwork. She is showing how the Chinese people—represented by the dolls—are denied autonomy and abilities to be self-directing adults.

Books and writing tools, bindings and blindfolds, suffocating plastic bags and crucifix-shaped wooden poles, play pivotal roles in her artwork. She is showing how the Chinese people—represented by the dolls—are denied autonomy and abilities to be self-directing adults.

Here, the dolls are more than just the “ugly babies” of her imagination. They are a reminder of how precious it is to have freedom of expression, freedom of communicating, and freedom of idea exchanging.

This is just a weekly doll blog, where I ask readers to offer up their two cents and to opine openly. It’s a pastime—a little slice of entertainment.

In China, this would be forbidden, and would be scrutinized for content and hidden subtext. Today I invite anyone who reads this to post a thought—not because you may want to, but rather because you are able to.

A rose is a rose is a rose, but a doll is a warrior for freedom. How sweet it would be, if a mere plaything managed to bring down a communist house of cards.