Mattel’s WWE Superstar dolls take a strong stand.

I have to say that I had a good feeling about Toy Fair 2018. As I rode into Manhattan via railroad, I was surrounded by people (like me) who were all lost in their own little comfort zones. Some were reading; some were playing with their phones; some were chatting. Everyone was occupied with something else, but one commuter stood out to me.

NY Doll company presented dolls that seemed real and relevant.

She was a young girl, perhaps 8 years old, and she was holding an American Girl doll, or a variation on one of those 18-inch-high doll confidantes. She was talking to her doll, and I swear it seemed that the doll was talking back. She was thoroughly engaged in a conversation that was not one-sided in her mind. (And, truth be told, I’ve actually had one-sided conversations with humans, where my dialogue degenerates into a monologue. Not everyone wants to talk all the time about everything!)

The NY Dolls do a very “New Yawk” thing, waiting for public transportation.

It made me happy to see this interaction as I headed to Javits Center because the art of doll playing seems all but lost. If there were some kind of Candy Crush game, with levels that measure affinity for the doll and a TLC meter that ticks off concern and nurturing, then the whole world would be doll collecting and doll playing. Instead, dolls—even the ones that gurgle and giggle electronically—depend upon a certain amount of human imagination. A child has to be willing to see that doll as a baby, a friend, a sister, or a role model. Without the child’s input, a doll is simply a piece of plastic or vinyl. It depends upon the human touch to humanize it.

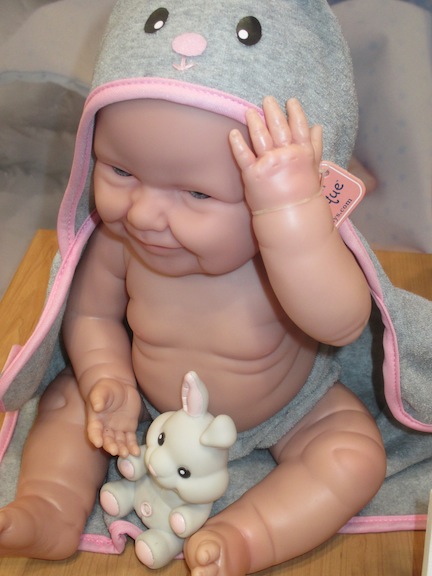

JC Toys are known for their precious infant dolls, loved by little girls and adults.

That was especially noticeable to me as I wended my way through the Javits Convention Center (which could easily be renamed the Javits Cavernous Center or just Javits Caverns). The place is enormous, and the number of miles of aisles showing toys is likened to more than a half-dozen football fields. Amid the staggering number of exhibitors, I was happy and pleased to see dolls, and dolls doing the most versatile things.

JC Toy baby with bunny and blankie bathrobe

That’s the beauty of being a doll maker and a doll collector. The doll is not programmed to do something that then leads you—the owner—to attain another level of success. A doll functions as one thing, and one thing alone: a receptacle for your love.

Beautiful, bouncy babies at FAO Schwarz

Whether it’s a fashion doll that showcases what we aspire to be (hence, the enduring success of Barbie for nearly 60 years) or the idealized baby—cherubic and never colicky, eternally newborn and never growing old—dolls embody what their collector desires and dreams about.

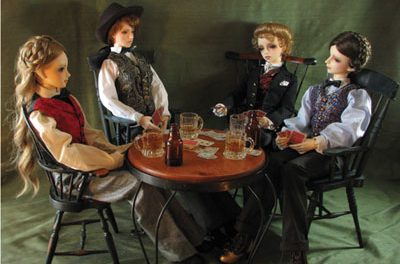

Sophia Dolls has costuming that reflects the outdoor lifestyle, able to be worn by male or female dolls.

Toy Fair 2018 was rife with dolls that reflect, to try to mirror, what today’s girls are all about. The clothing was more streamlined and reflective of the real world, not that many flouncy dresses and acres of petticoats. The girl dolls were dressed to tackle outdoor sports, with Title IX helping them to attain those soccer or football goals that once only belonged to their male schoolmates. At Toy Fair, so many of the dolls were garbed as athletes or, at least, athletic young women. Their creators also supply home turf for them, so it’s not just a dream house that the dolls can retreat to. It’s also a camper, a stable, a locker room/sauna, and a wide variety of outdoor possibilities. The dolls of 2018 have places to go and mountains to literally climb.

This Paradise Kids advertising slogan says it all!

It’s ambitious to be creating dolls that are so active and physical. The young girl that I saw on the train in the morning might be a star soccer player or basketball shooting guard. I wouldn’t know. No self-respecting mom would permit her daughter or son to bring a ball onto a railroad car and then let them start to showcase their skill sets. Balls are for courts and fields; dolls are for everywhere else.

The Paradise Kids line had a huge array of action-packed sets for girls and their dolls.

That’s a major takeaway from Toy Fair. While girls have been encouraged since the mid-1970s to participate more in sports—shown that a career in athletics can be theirs, not just their brothers—they have not been enticed to play with dolls. If anything, a doll has often been associated with “toxic femininity.” (You know that has to exist in some people’s minds; it’s the antonym yet similar rallying cry of “toxic masculinity.”) While young girls have been tempted and propelled into becoming more jock-ish and more competitive, dolls have been pretty much ignored, except for at Halloween where they pop up as evil doers and villains.

Sea World doll to the rescue! Lovee Doll presents a caring and courageous doll.

But dolls, for the other 364 days of the year, seem to be a very select, very small niche of the collectible and play market. What can be done to change that? What can be created to have dolls remain relatable, relevant, and real?

Glitter Girls know how to shine, even when visiting their stables.

At this year’s Toy Fair, I think the game plan—to borrow a sport’s term—is to make dolls reflect what girls are being pushed to pursue. Just as a girl may never grow up to be a runway model, a movie star, or head cheerleader, she could fantasize about it via her Sindy, her Gene, or her Barbie. The doll was wish fulfillment.

Lori Dolls provides cool and speedy vehicles for their dolls (and yours) to get around!

The same holds true for these new dolls that seem to have all the answers for outdoor fun and games. They are able to ride horses, catch trophy-size fish, careen in racecars, and score series-winning points. The new dolls are able to pin an opponent in a wrestling ring, not worry about getting “pinned” by a fraternity sweetheart or receiving a ring from a smitten suitor. These are dolls that could do an episode of cable-TV’s “Naked and Afraid” without batting an eyelash. They’d never show fear, and they’d never have to worry about their anatomy being blurred out.

Mattel’s WWE Superstar Fashion Dolls reflect a world of beauty and brains.

Truly, in 2018, the world of dolls is surviving. But it is surviving by presenting dolls that could easily win the reality show “Survivor” without breaking a fingernail or losing their stride. Dolls are getting stronger, as real-life girls are doing the same. It’s eerily similar to that cult film-favorite “Fight Club,” where the participants don’t talk about their membership. We all have to put aside the first rule of Fight Club: You don’t talk about Fight Club. (That’s the second rule, too.) Instead, we have to talk about our attachment to dolls, and be willing to fight for it, too!