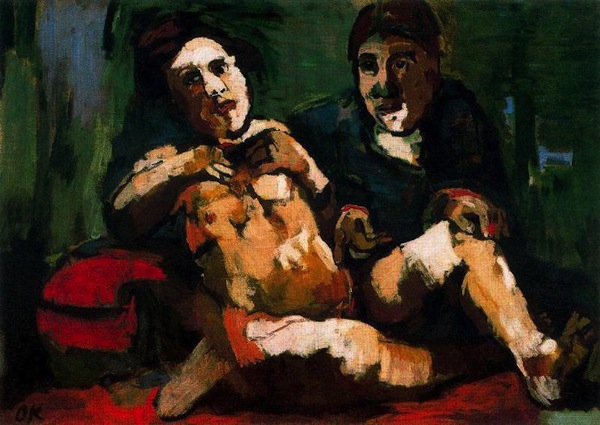

“Oskar and Alma Double Portrait,” Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

Whenever my friend Mickey gets dangerously close to ending his love affair with glamorous fashion dolls, he always frets that he is one twist-and-turn waist away from turning into Oskar Kokoschka. When he says that, both of us groan, giggle, and then quickly groan again. For the uninitiated, Oskar Kokoschka is the embodiment of the world’s quirkiest and ultimately destructive doll collector. I’ll tell you the story of Oskar as Mickey and I have learned it.

Back in the early 1900s, in the glistening and glittering salons of Europe, young, aspiring painter and author Oskar Kokoschka met an older woman named Alma Mahler. Alma was the widow of the renowned composer/genius Gustav Mahler. Apparently, Oskar fell under her spell and she quickly ascended to becoming his lover and overwhelming muse. (In Alma’s defense, beyond being like catnip for creative men, she was also a talented musician and composer in her own right. She just happened to be a magnet for a series of artistic lovers, husbands, and stalkers!)

At this point of the tale, Mickey always chimes in that when Oskar wasn’t busy bedding her, he was painting her! As blunt as that sounds, it’s very true. They apparently had an extremely hot and heavy physical affair, and Oskar spent hours, days, weeks, and months sketching her, drawing her, painting her, and memorizing her. Suffice it to say, he knew every inch of her — the way a doll collector knows every part of a favorite plaything.

When their coupling eventually cooled down, Oskar was devastated. Alma claimed that she had to break it off because she feared being totally consumed by his fiery passion. In other words, she loved him so much, she couldn’t bear to be with him any longer.

(“Bride of the Wind,” 1914, Oskar Kokoschka, Kunstmuseum, Basle)

Even though this breakup was piggybacked with that backhanded declaration, Oskar didn’t handle it well. He enlisted in the Austrian Cavalry while World War I was in full swing. During his military service, he was severely injured and suffered “shell shocked” episodes twice. His doctors felt he had become mentally unstable. When he returned to civilian life, he could not get things going again with Alma. As Mickey always observes, “That Alma cougar was one cool customer.” She didn’t want to become entangled with him any longer.

Now, remember that for three years, Oskar did nothing but woo her and replicate her. He had rooms filled with tributes to her. All of those drawings and sketches were easy enough to translate into blueprints. And that is just what he did. Oskar hired a dollmaker named Hermine Moos (I am not making up that name) to translate his muse into a life-size doll! I first learned about this bizarre occurrence when I saw an off-Broadway play about this artistic breakdown/meltdown. In fact, the full-figured Alma doll in the show was made by one-of-a-kind artist Nancy Wiley. So, I know how crazy and compelling this whole event eventually becomes.

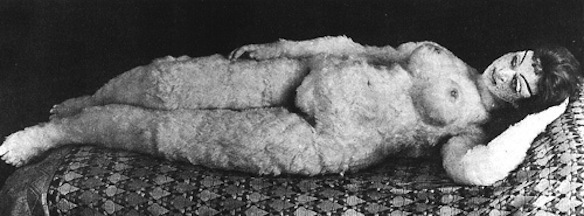

(Hermine Moos with life-size doll. Photo courtesy of Guggenheim Museum)

Hermine Moos was commissioned to create as lifelike a doll as she could possibly conjure. It definitely was a doll that had to stand up to constant attention. Oskar planned to dress and undress it, kiss it and sleep with it, travel around with it and have it co-host parties at his apartment. He was very specific that he wanted the doll’s skin to be soft and supple to the touch. Whether she was really trying to make the doll soft and inviting, or if she felt that his demands were “cuckoo,” Hermine Moos covered the doll’s upper torso with feathers. That skin choice surprised Oskar, but he didn’t refuse delivery. He took the doll into his home and began a life of courting it.

The timeline for this doll dalliance varies, but many people feel it was a three-year faux affair. (The same length as his relationship with the flesh-and-blood Alma!) During this time, he painted it repeatedly, sketched it, drew it, adored it. His servant reported that he would hire coaches to take the doll out for evening rides, and he even bought opera tickets for him and the doll. They would sit together in a box — Oskar and his “Silent Woman,” as the doll came to be known.

(“Self-Portrait with Doll,” Courtesy of Visual Arts Encyclopedia)

In late 1921, it is said, right around the three-year mark, Oskar ended the relationship. He held a party where artists and courtesans, novelists and aristocrats, attended. The Silent Woman sat and watched all the revelry around her. At one point, Oskar declared that he had had enough. Drunk and spurred on by his guests, they dragged the doll out to the back garden of his building and he beheaded the doll. Then they took turns spilling glasses of wine over its head.

(Photo courtesy of Guggenheim Museum)

The next morning, police received word that there was a decapitated woman lying in broad daylight, covered with red stains. When they went to investigate the supposed homicide, they saw that was simply a doll that had been severely manhandled.

Mickey loves this story because of its scary, over-the-top, obsessive details. (When it comes to his Gene dolls, he really does think that this kind of acting out is in his genes!) He often wonders if he’ll ever get to that point when too many dolls, too many costume options, too much of everything, will lead him to rip the head off his dolls and strew their torsos in the tulip beds!

With each new purchase, or each worrisome trade and swap, Mickey always sighs that his Oskar Kokoschka moment is just a single sale away. I always tell him that it will never come to that. His dolls are his dolls, whereas the Silent Woman was an Alma duplicate.

That always calms him down. “I’ve always dreamed of an Oscar-worthy life,” Mickey states. “I just don’t want an Oskar one!”