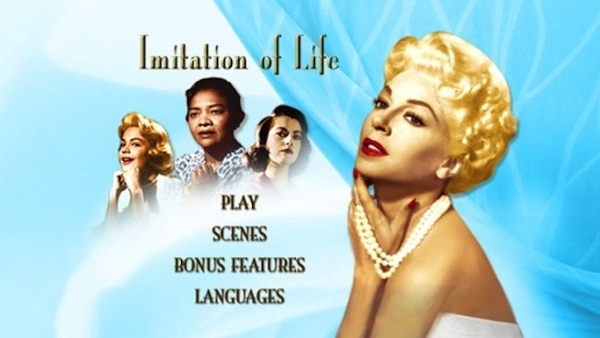

“Waterloo Bridge,” a 1940 quadruple-hankie tearjerker movie

Vivien Leigh passed away 50 years ago, and during the ensuing decades, her personal life has been mined by both celebrity biographers and mental-health advocates. Leigh lived as a woman with bipolar disorder, and many clinicians now feel that misinterpreted diagnosis played a very strong part in her oft-rumored mercurial and misunderstood behavior. Slammed by some producers and co-stars as “tempestuous, unpredictable, and erratic,” Leigh was fighting to carve out a career for herself, one that allowed her to shine independently of her famous and adored husband, Sir Laurence Olivier. It’s not a simple case of “poor little rich girl,” but rather “poor little talented, beautiful, and passionate rich girl.”

A Tonner Doll Company version of Vivien as Scarlett

Leigh has been a muse for many doll artists because of her iconic role as Scarlett O’Hara. Born in Darjeeling, Bengal, part of colonial British India, Leigh seemed every inch the proper English Rose. It was her commitment to assuming the dialect, the accent, and the costuming (including heavy drapes) that turned her into the Southern belle of all belles. Even contemporary star and rival Bette Davis’s turn in the Southern potboiler “Jezebel” fades when it is measured against “Gone with the Wind.”

Embodying Scarlett (the height of Southern femininity) and Blanche DuBois (the nadir of a Southern woman), Leigh had an uncanny ability to portray women who were simultaneously vulnerable and fierce, unbreakable and broken. She was a consummate performer.

Tom Tierney’s paper-doll dresses for Scarlett

Beyond her enshrinement as Scarlett, and all the dolls and collectibles she launched, Vivien Leigh is also strongly identified with one of the oddest doll crazes of all time: the Billiken. In filmdom’s most famous tearjerker, “Waterloo Bridge,” Leigh played a character named Myra, who endures one indignity after another. From a naïve young ballerina, with the world at her feet, to a desperate, unhappy prostitute, who eventually throws herself beneath an oncoming truck, the role of Myra afforded Leigh the opportunity to play every attitude, emotion, and physical reaction that exists for movie actresses.

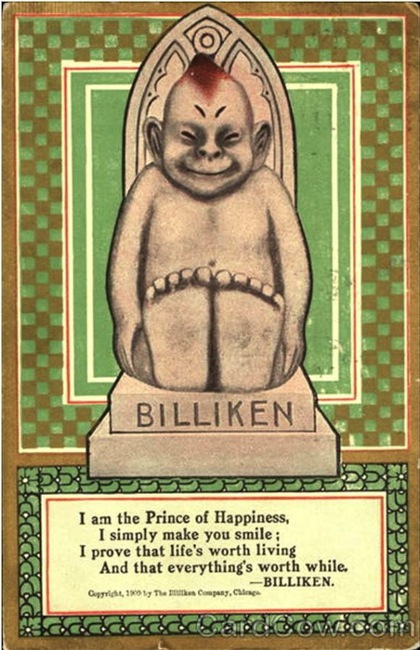

The Billiken good-luck charm from “Waterloo Bridge”

The Myra character gives her lover — a dashing but ill-fated soldier, played by Robert Taylor, destined to become a prisoner of war, and thus remain separated from her for years — a good-luck charm called a Billiken. Now, most of you are probably wondering what the heck that could be!

“Waterloo Bridge” was made in 1940, a year after “Gone with the Wind,” and it takes place in the days leading up to World War I. While Leigh sizzled in “Wind” against a Technicolor-drenched backdrop, here she is filmed in crisp black-and-white for this period piece. In addition to the clothing that is circa 1914, so is the little Billiken, a made-up god — yes, you read that right — that captured public imagination in the few years that preceded “the war to end all wars.”

Florence Pretz

The Billiken was invented in 1905 or 1906; its creator did not file for a patent until 1908, and when she did, she didn’t file for an effective one. Invented by Missouri’s Florence Pretz, the Billiken was the mascot of America’s first self-help wave. Convinced that the 20th century would be a magnificent one — a century of innovations, inventions, and better living for everyone — Pretz dreamed up a god that embodied the positive side of life. Over the years, she claimed that the Billiken came to her in a dream — a vision of promised prosperity and enchanted posterity. Other times she said she was a reincarnated Japanese woman who had had hallucinations and encounters with the smiling, impish god. Still, other moments found her saying that she had read a poem, “Mr. Moon, a Song of the Little People,” published in a Canadian magazine and saw the exotic name listed among a host of fantastical fairies. Suffice it to say, Ms. Pretz had as many explanations as there are hours in a day.

A Billiken poster

Florence Pretz and her best friend, Sarah Hamilton Birchall, were attractive, young, smart, and ambitious. (Vivien Leigh could have easily played Pretz in the story of her life.) They were also self-promoters of an unequalled stripe. With Pretz drawing and sculpting the Billiken, and Birchall writing songs, poems, and short stories extolling its virtues, the two managed to attract the attention of newspaper reporters. The cigar-chomping writers loved to come out and photograph the two young ingénues at the Chicago, Illinois, flat they shared.

Playing up the power of the Billiken, Pretz and Birchall swore that they worshipped at a shrine built to give the god an elevated place in their apartment. They wore kimonos and burned incense. They rattled off prayers to the godlike imp. All the while, a savvy publisher was gathering together their quotes and their antics to make it into a Billiken bible of sorts.

Billiken sheet music

The philosophy of this American-made deity was one that Dr. Phil, Dr. Oz, and Oprah could get behind. (Even Mad Magazine’s Alfred E. Neuman, with his “What Me Worry?” motto!) It involved being happy and thinking positive thoughts whenever possible. His alternate names became the God of Luck, the God of Things As They Ought to Be, and the God of Happiness. It was said that to buy a Billiken was a promise of good luck and charmed protection; to give one to a friend was even more of a guarantee for their future fortune.

An early 20th-century postcard

From 1908 right up to the eve of World War I, the Billiken was everywhere! He was on jewelry, on stationery, on dishes, and made as dolls. The Horsman Company had great success manufacturing his three-dimensional likeness. Depicting a mind-set of everything as it ought to be — good health, plenty of cash, good dreams, and lucky chances around every corner — the Billiken was a magnet for people who were in need of better times and better opportunities. The outbreak of World War I, and the heavy casualties and fatalities that followed, put the god’s power to bed for good.

Doomed lovers in “Waterloo Bridge,” despite the good-luck doll

Florence Pretz, the “mother” of the Billiken, did not handle her business affairs properly. Rather than netting a fortune from the net of good intentions that he represented, Pretz was only getting about $30 a month from the collectibles’ sales and merchandising. The businessmen who had helped her and Hamilton Birchall spread the word and the imagery ended up helping themselves to the lion’s share of the profits.

So, it makes perfect sense that in “Waterloo Bridge,” the innocent waiflike ballerina played by Vivien Leigh would give her Billiken to the soldier who is heading off to the Front and to an unknown, possibly deadly, future. She wants to protect him, so she gives him the one thing that she has faith and belief in.

A statue to the Billiken on the Saint Louis University campus

With the collapse of the world’s stock market in 1929, and a Second World War brewing ferociously when “Waterloo Bridge” was released in 1940, the Billiken was a clue that things would not work out for these doomed lovers. Watching it as a modern filmgoer in 2018, we see everything in this movie as nostalgic and a paean to bygone days and etiquette. What do we know of Billikens? (Unless you are a native of St. Louis, Missouri, where it serves as a sports mascot for university and high-school teams.) To people who filled the cinemas in 1940, they knew that the good-luck movement had been debunked. They knew immediately that the innocent gesture of giving over a charm would not reap any benefits or rewards.

SLU mascot

The rise and fall of the Billiken is an interesting footnote in the doll world and in the realm of positivity. This notion of controlling one’s own destiny with positive mind power has gone in and out of fashion over the decades that have followed the Second World War. Whether it’s an “I’m okay, you’re okay” mantra, a handbook of Scientology and Dianetics, or the lectures of Dale Carnegie and the sermons of Norman Vincent Peale, people have always clamored for a more positive, more rosy future. The Billiken provided the hopes for a generation of young women, and two women in particular, from 1906 to about 1914. It was an eight-year run of unbridled happiness and expectations, until the world and a war caught on fire.