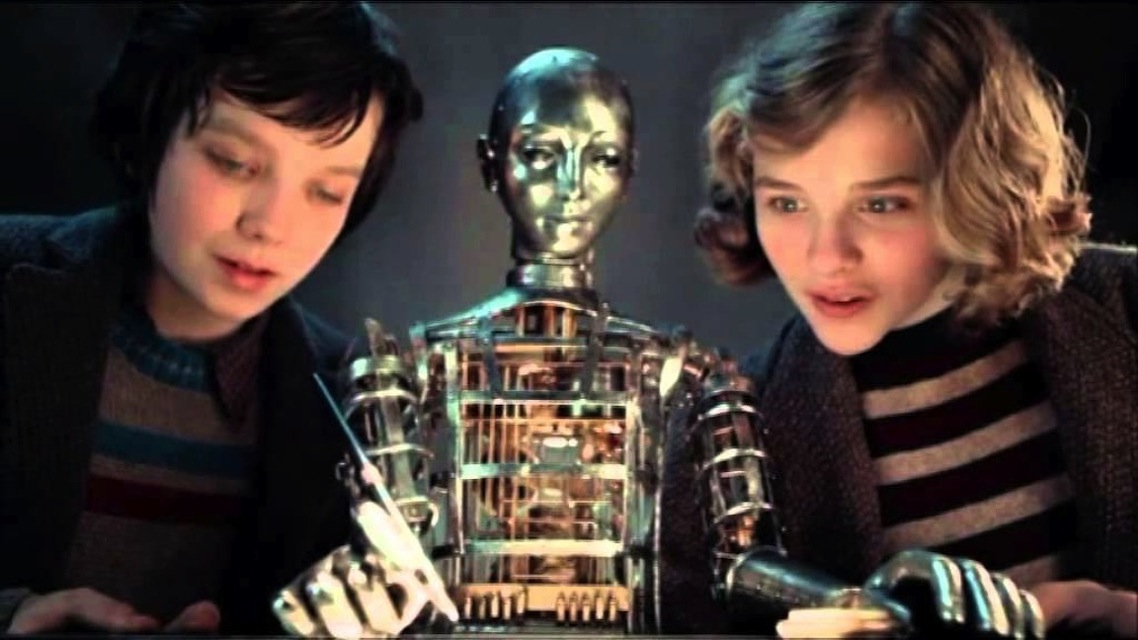

In October, “Hugo” will be screened against a mechanical backdrop.

Photos courtesy of the Morris Museum

About a decade ago, I saw a really fascinating documentary. It was called “Born Rich,” and it was made by one of the heirs to the Johnson & Johnson pharmaceutical company. James “Jamie” Johnson is the heir apparent to all of that wealth — we’re talking about oodles and boodles and maybe even poodles of money! He is going to be richer than most of us mere mortals will ever dream of being.

Pierrot — Ecrivain, one of the mechanical marvels in Morristown, N.J.

Rather than just sitting at home and counting bags of money, or ordering his butler Jeeves to operate the calculator, Johnson decided that he wanted to do something. He didn’t want to be a playboy or a man of leisure. He wanted to have a sense of purpose and a daily mission to occupy his psyche and his body. (Keep in mind that old tried-and-true proverb: “Idle hands are the Devil’s playthings.”) So, Jamie Johnson pursued a career as a journalist and a filmmaker. In 2003, at the age of 24, he released a look at what it means to be phenomenally wealthy. Among the scions of capitalism that he chatted with were Georgina Bloomberg (daughter of billionaire Michael, onetime New York City mayor and soda czar), S.I. Newhouse IV (heir to the Condé Nast publishing empire), and Ivanka Trump (model, businesswoman, and daughter of the current U.S. president, Donald).

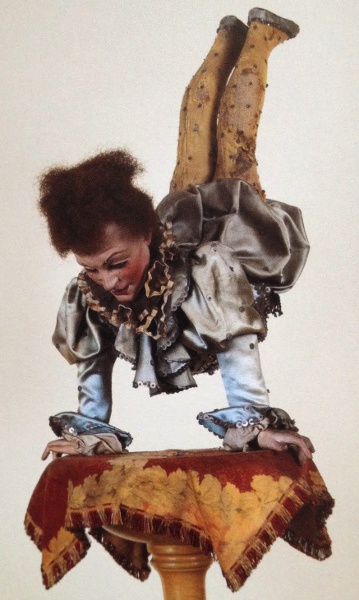

A beautiful performer is one of the many mechanical treasures in the Guinness Collection.

What emerged was that these super-rich individuals all had different notions of what it meant to be busy, occupied, and engaged. For some, it was a chance to pursue an avocation/hobby as a full-time career (equestrienne and show jumper). For others, it was an opportunity to take part in the family empire and try to shape it for future generations. Still, other heirs and heiresses had no intention of doing anything to fill their days. They were quite happy simply to exist and to follow their hearts and where the path of 100-dollar bills led them (parties, balls, getaways, permanent vacations).

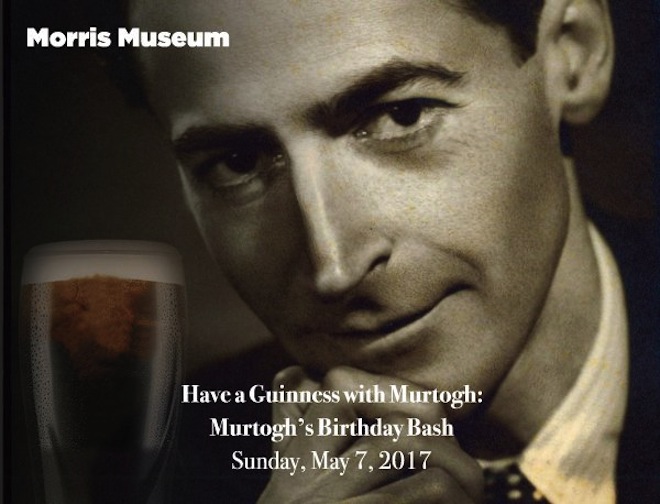

A promotional celebration held at the Morris Museum.

I bring this up because I stumbled upon a museum this week that I had never attended before. It is the Morris Museum and one of its largest distinctions is that it houses the permanent Murtogh D. Guinness Collection. Now, who, pray tell, is Murtogh D. Guinness, and what was he collecting? Guinness was part of the fabulously well-to-do Dublin brewing clan, and a distant relative to the Guinness family that preserves and collects all those World Records, too. Loaded with cash, and knowing he never had to grow up to choose any necessary employment, Guinness was free to engage with what attracted his fancies. As it turned out, and the museum is top-notch in its presentation of this, young Murtogh received a spring-wound music box at the age of seven and his life was never the same again.

Entrance to the exhibition of the collection.

His mother had taken the second grader to a fine Swiss watch shop and allowed him to pick out a timepiece to call his own. Rather than getting a wristwatch or a pocket watch, the young lad chose a music box and became obsessed with how it was built, what it did, and how it sounded. It was 1920 and the little boy recorded his happiness about getting this mechanical diversion. He wrote a note about it and taped it to the bottom of the box. This first possession, and his impromptu letter regarding it, was Guinness’s first step in a lifetime of collecting, chronicling, and comprehending. As a seven-year-old, he instinctively knew it was essential to write down the specifics of his new acquisition. This inherent knowledge grew and multiplied as he continued to acquire other music boxes, nickelodeons, and animal and doll automatons. The purchasing of these centuries-old mechanical marvels became his profession. He dedicated his working time, pastime, leisure time, and lifetime to buying the best of the best.

This maid moves to dust the portrait.

Married, but having no children, Guinness filled the home he shared with wife Nancy with fidgety figurine after fidgety figurine, dancing doll after dancing doll, agile acrobat after agile acrobat. Their Upper East Side town house eventually became so crowed with mechanical balancing clowns that he bought the town house next door. Soon, both his properties were stuffed to the gill with nearly 800 antique objects and over 5,000 interchangeable cylinders and discs to make the music of his beloved boxes and calliopes.

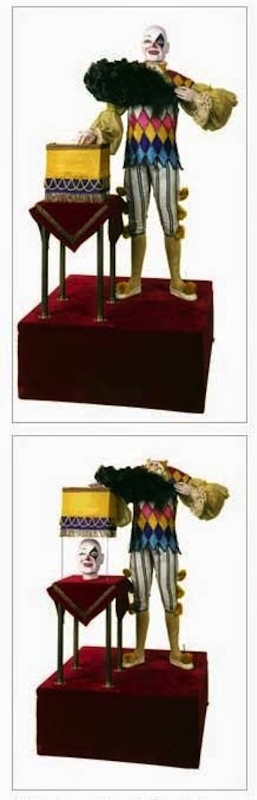

Clown that appears to lose its head.

What is fascinating about Murtogh D. Guinness and his collection is that it was a pastime — a person could argue it was a time-waster paid for by his inherited trust-fund payments. True, he wasn’t deriving any income from how he filled his days and nights, but he was deriving a fulfilling sense of purpose. By reading about, studying, investigating the history of automata, he developed a discerning eye that allowed him to handpick the finest examples of these articulated devices. At the Morris Museum, they have created a room that approximated his parlor at one of his town houses. It is filled with gadgets as far as the eye can see. The docent for the tour I was on reminded us attendees, “This just gives a sense of how he was living with his collection. This room is actually less crowded than the real one at his home.”

One of many agile acrobats on display.

The museum has several rooms filled with the Guinness Collection, which was handed over to them in 2007, after his death at age 88 in 2002. As the former president of the Music Box Society, and a major benefactor to the arts community, he had a keen understanding of what a collection can mean and how it can impact the people who view it and react to it. Among the edicts of his will was that the collection had to be kept together, a large majority of it had to be on public display, a portion of it had to be demonstrated to the public, and the items had to be looked after, repaired, and maintained in proper, working order. Morris Museum fit the bill and even built a new wing on their edifice to meet these demands. One of the interesting facets of the bequeathing was that a full-time/built-in curator came with the inheritance. A Guinness family friend named Jerry Ryder, who was trained in the art of restoration and manufacturing of automata, came along with the treasure trove.

Wound-up, life-size, mechanical Floutiste.

Wandering through this unassuming, from the outside, building in suburban New Jersey, I never could have imagined that there was such a universe of unique and beckoning characters inside. The doll-like figures ran the gamut from innocent children to erotic belly dancers, Far East exotic performers to music hall magicians. The characters did sleight of hand, tried on and removed masks, waved hello and good-bye, and eerily approximated all manner of human behavior.

This exotic woman teases spectators.

It is truly a wondrous experience to see so many of these carefully collected and maintained characters as they stare plaintively at you through their glass display cases. The portion of the collection that isn’t on the main floor is stored in the museum’s basement, and visitors can go downstairs to see some of what is tucked away. Those cellar dwellers are stored in temperature-controlled climate containers, and some of them can be peered at through glass. After an hour of interacting with the upstairs residents, one can’t help but feel bad for the secreted-away creatures. (I know, I know, they are all inanimate objects! But, gosh, they seem so lifelike.)

Buffet Magique

If you are ever in New Jersey and want a taste of how a wealthy heir decided to spend a portion of his private fortune — but all the while, making sure that it would become part of the public sector — take a stroll through the Morris Museum. It has a little bit of everything and works as a great aperitif to whet the appetite of museumgoers to want to go out and see bigger and grander institutions. It is an ideal bridge to culture for schoolchildren and local residents. However, its Guinness Collection is second to none. It stands, and moves, and dances, and thrills, on its own two mechanical feet.

“Hugo” attendees can build their own automaton, taught by the curator.

I am so happy I had the chance to experience it, especially during its 10th Anniversary events, and I urge others to take the trek there. It is a way to understand how a collection can take over an individual’s living space and his life. And if preserved properly, it can go on to have a life everlasting. Murtogh D. Guinness has attained immortality through his musical and mechanical marvels. I think he would be humbled and proud to know that his obsession is the basis of a museum’s individual identity and collective exclusivity.

Murtogh D. Guinness is remembered and honored by his collection.