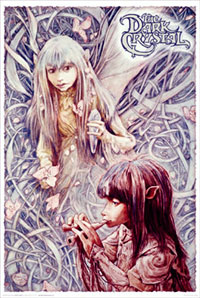

(Berthe Morisot believed in the inseparable tie between little girls and their dolls.)

Photos Courtesy of Princeton University Archive

It was more than a simple, pleasant surprise when I discovered the Impressionist exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum. It was actually a joyful moment — a great mating of happenstance and happiness. After all these years of residing in the Garden State, and trekking out to Princeton for theater and walking tours, I finally went into the campus’s fine-arts museum … and, oh boy, was I glad! (Though for purposes of this week’s posting, I suppose I should say, “Oh girl, was I glad!”)

This week’s musings have to do with my afternoon at the museum and my heartfelt appreciation for early pioneer artist Berthe Morisot. If you’re like me, you have a working knowledge of many of the famous artists of the past — Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Monet, etc. — as well as familiarity with some of the biggies of the post-World War II years. I love to lose myself in a painting, and especially have a soft spot for the pastel and pastoral depictions of 19th century France and England. That’s why I was so pleased when I came upon the paintings of Berthe Morisot. I have to confess I had NEVER heard of her, though I knew two of her female peers: Mary Cassatt and Marie Bracquemond. For some reason, her name never popped up on my radar, and — oh, girl — I am overjoyed that it finally has! She depicts a universe filled with calm, tranquil interludes between children and nature — and children and their precious dolls!

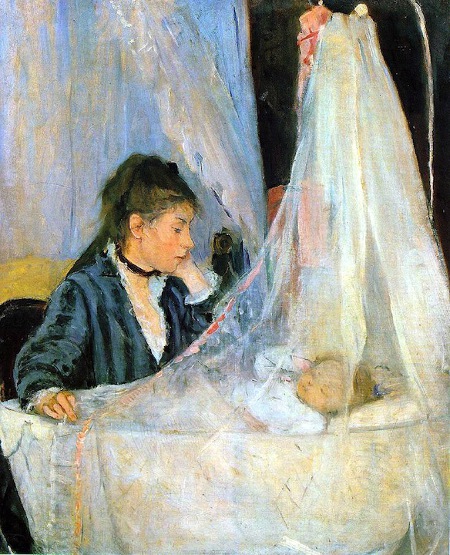

(1872’s “The Cradle” is the most well-known portrait that Morisot painted.)

Berthe Morisot has a fascinating professional and personal life. Though her name eluded me, her most well-known painting (“The Cradle”) has been incorporated into calendars, gift cards, textiles, and duplicated as a poster and print. That is one of the hallmarks of her “oeuvre,” she painted the everyday niceties of her worldview, and much of it featured her sisters, her nieces, her husband, and her daughter, Julie. While she always painted using her maiden name, her married name would have pinned her as a recipient of nepotism (which she wasn’t). Morisot’s “other” name was Madame Manet — that’s right Manet, as in the painter of “The Luncheon on the Grass” and “Olympia,” two canvases that are credited with changing the way the world looked at art.

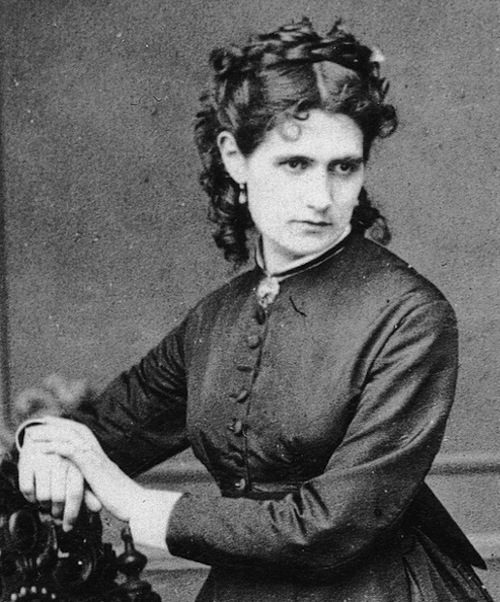

(Berthe was a muse for her brother-in-law Edouard Manet on several occasions.)

The legendry artist Edouard Manet was Berthe’s brother-in-law. She was happily married to the painter’s brother, Eugene. Her immersion in the world of artistry predated her marriage to Eugene in 1874. She met aspiring painter Eugene through her friendship with Edouard, whom she studied with, posed for, and socialized with. One of the interesting things about Berthe’s relationship with her brother-in-law, Edouard, is that she would talk to him as one accomplished individual to another. She never saw herself as his protégée, or he as her master. She regarded them as equals — but equals that were not enjoying the same amount of notoriety.

(Berthe adored the chance to chronicle her life, such as this look at husband Eugene and daughter Julie.)

Whereas Edouard Manet sowed the seeds of scandal — how’s that for alliteration — with his depictions of people dining “al fresco” in the “altogether” (meaning, nude), Berthe concentrated on depicting afternoons spent sewing, playing hide-and-seek, learning to master the violin, and enjoying an idyllic romp in the park in pursuit of butterflies. While Edouard Manet made a name for himself by employing known prostitutes or “ladies of the evening” to be his models — and then encouraging them to stare brazenly at him, and, as a result, at the paintings’ viewers — Berthe primarily focused on venerating the virtues of being at peace with one’s setting. Edouard Manet played up the body; Berthe Morisot highlighted the homebody.

(A girl and her doll — the artist returned to that time and again.)

Her series of paintings that couple little girls with beloved dolls — and her daughter, Julie, is frequently one of the children that she captured in that pairing — are beautiful and enchanting studies of innocence and whimsy. She manages to make the notion of make-believe and a child’s reality one and the same. For children, the bond that they share with their dolls is a private and intense one. Parents can acknowledge that a child loves her doll — can’t bear to be parted from it. However, it’s hard to measure how much affection the child is bestowing upon the doll — and how much she believes she is receiving in return.

(Right up until her death in 1895, the doll motif was one of Berthe’s favorites.)

Berthe painted this tight connection between girl and doll many times. She rendered it in a lovely and loving way. Throughout her brief life — she died of pneumonia in 1895, at age 54 — she created a canon of artwork that chronicles a devoted mother’s take on her child’s growing-up, formative years. She also extended her painting to go beyond just her biography and her personal experiences. She welcomed the chance to showcase the accomplishments of other females in her social circle, her patrons’ milieu, and the goings-on of unknown women throughout the French countryside and suburban enclaves.

(A photograph of and self-portrait by French Impressionist, Berthe Morisot.)

Her death came as a result of nursing her daughter, Julie, through her own near-fatal bout of pneumonia. When Berthe passed away, Julie was 16 years old. She was orphaned — having lost her father, Eugene, in 1892. The sadness of losing her mother — who was her nurse, her guardian, her teacher, her greatest advocate — was a true devastating blow. However, she did have the paintings and portraits, sketchbooks and preliminary drawings, from her mother to remind her of those golden childhood days spent on her family’s veranda, with her trusty doll always at the ready.

(“Doll on the Veranda” celebrates the omnipresent doll that figured in the Morisot-Manet household.)

Now, more than 120 years after her demise, the achievements of Berthe Morisot, which were revered in her life, but then left to linger in obscurity for many decades afterward, have been revived and displayed once more. If a show celebrating the Impressionists is mounted at a museum near your home, try to find time to attend, and search out her handiwork. It is an invitation to grace and gentility.