Valentine’s Day is a celebration of the romantic aspect of love. Yes, over the past 20 years, it’s broadened its appeal to include love of family, friends, even pets. It’s no longer just a day for sweethearts to swap affection. Rather, it’s a day where everyone can openly proclaim their feelings for all the folks that make them happy. Still, however, the symbol of a kiss best defines Cupid’s holiday. And when one thinks of a kiss, Gustav Klimt springs to mind. He is the timeless painter of “The Kiss.” And as we all know, a kiss is not just a kiss. A kiss can have layers of significance, and so does the story of the man who painted that classic embrace.

Klimt was born in 1862 in the Austrian Empire. His parents were both considered artistic intellectuals. His mother had always dreamed of a career as a concert performer; his father was a gold engraver. The Klimt family was a large one, and by virtue of its growing size, the members never seemed to have enough currency to make ends meet. There were seven children in all, and the three sons (Gustav, Georg, and Ernst) displayed artistic talent from a young age.

Gustav Klimt decided to gain a formal education in the arts and headed to Vienna. He studied architectural painting for seven years, from 1876 until 1883. He and his brother Ernst, along with two friends, founded the Company of Artists. The quartet sought out commissions for murals, frescoes, ceiling art, and other adornments for public buildings. The two Klimt siblings seemed to have attained financial success and were riding high.

Then, in 1892, Ernst died suddenly. That same year, Gustav’s father passed away. He was now responsible for supporting his mother, his siblings, and his deceased brother Ernst’s family. The overwhelming responsibility, the unexpected tragedies, the realization of how fragile life is, dramatically affected him. Gustav lost interest in the work-for-hire routine. Even though he had received the Golden Order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I, he was willing to walk away from a guaranteed income as a public servant. Instead, he began to mine his own visions and his own passions.

Right around the time that Klimt declared his professional independence, he met the woman with whom he would become dependent and devoted. Her name was Emilie Louise Flöge, and she was the sibling of his sister-in-law, Helene. Now responsible for Helene, who was Ernst’ widow, and her extended family, Gustav became Emilie’s guardian. He was 30 years old; she was 18. The young teen was a free spirit and an iconoclast. She and her older sister Pauline were both outspoken feminists. They were also both handy with a needle and thread.

Pauline opened a dressmaking school, and Emilie joined her staff. Emilie’s patterns were gaining notice, and soon the sisters’ handiwork was the talk of the town. The two young women were growing more and more self-sufficient while earning a pretty penny as fashion designers. They were in demand.

Meanwhile, Gustav was achieving wild successes and horrible disasters. His preference for painting women in full nudity — he said it was to expose the truth behind lies — was being slammed as pornography and showcasing indecency. His young ward soon became his most loyal companion and advocate. She moved in with him, and they remained together until his death in 1918. (He was a victim of the worldwide influenza epidemic that infected 500,000 people.) His last words were “Get Emilie”; his companion and confidante was always on his mind.

Gustav and Emilie shared an unconventional life. They never married, and some people say their relationship was never consummated. Though they did hold hands, hug, and show great affection toward one another, some historians suggest that Gustav had idealized her. Because he had placed her on such a high pedestal, he did not want to risk toppling her off with “too-intense” physical contact.

However, one of Gustav Klimt’s most famous paintings is “The Kiss,” and it is frequently speculated that he and Emilie were its models. When it first debuted in 1908, the painting was called “Liebesparr” (“The Lovers”). It is an oil-on-canvas painting with gold leaf, silver and platinum. Painted during his so-called Golden Period, the two lovers are captured in an amorous moment. Their bodies are intertwined and their silhouettes are swaddled in Art Nouveau robes. It is Klimt’s most enduring canvas.

Ironically, at home, Gustav and Emilie dressed in homespun, humble lounging gowns. They wore sandals or moccasins and no undergarments. They ate simple fare and shunned large social gatherings. It’s been whispered that various female lovers visited Gustav at his studio — and some researchers say he fathered perhaps 14 children with these paramours. He kept these dalliances discreet and out of the public eye. He did not want to embarrass Emilie nor draw attention to his private couplings. Gustav trod that difficult tightrope between revealing his inner thoughts and then struggling to safeguard his soul.

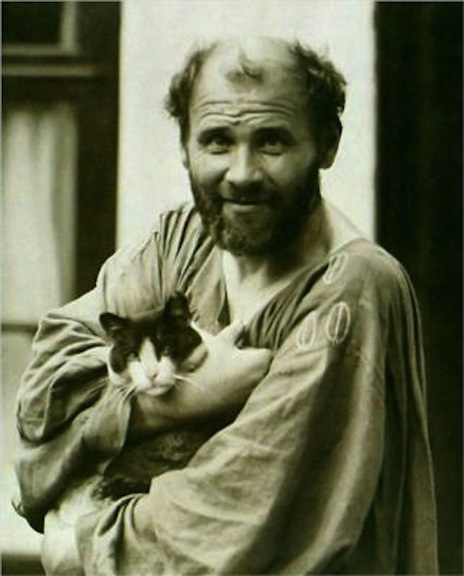

Along with his beloved Emilie, who lived until 1952, 34 years past his death, the artist shared his house with a colony of cats. There were dozens of feline companions jumping and scratching, racing and slithering, all around his studio and living quarters. His favorite of the cats was Katze, which he cuddled in the most famous photo ever taken of him. Clad in one of his trademark tunics, Gustav beams as he cradles Katze. In this 1912 black-and-white portrait, he looks like a wizard or a mage.

When the critic Arthur Roessler visited Gustav’s private lair, he was shocked to see how the cats ran the place. “I was surrounded by eight or 10 mewing and purring cats,” he wrote. “They ran wild through heaps of sketches.”

Roessler asked Klimt how he could allow such pandemonium, and his reply was quite Zen: “It doesn’t matter if they crumple or tear a few sheets — they piss on others, and don’t you know, that’s the best fixative or glue.”