Kazuyo Oshima was born on the Awajishima Island of Japan in 1946, just one year after the defeat of World War II. At the time the Japanese were very poor, far from where they are today. Her father, an atomic bomb victim, worked entire days in the fields as a farmer; while her mother, a kimono dealer without a shop, daily rode a bicycle piled up with merchandise selling her goods. Meanwhile, little Kazuyo was left at home during the day playing with dolls, such as “Ichimatsu-ningyo,” fashion dolls, or popular toy dolls like “Dakko-chan” (manufactured by Takara in 1960). The dolls were gifts from her mother, who wished she could spend more time with her daughter.

As a girl Oshima was not good at communicating with other children. However, the tiny dolls she created from mud or twigs, her drawings or objects she made of trifles drew her classmates’ attention and praise. When Oshima saw her friends smile while looking at her creations, she felt a feeling of pleasure that made her feel understood by what she made.

When the time came for her to decide on a course of study at university, her parents hoped their high-achieving daughter would choose to become a doctor. Instead, Oshima decided to specialize in painting. She moved to Tokyo, and passed the exam of Tokyo University of the Arts, the top art university in Japan. There, she majored in oil painting as an undergraduate and mural painting as a graduate student. During these years, she married a fellow artist, Makoto Oshima. After graduation, she gave birth to a son, and shortly afterward, the family moved to Paris in 1976.

While first living in Paris, she supported her husband as a wife, brought up a baby as a mother and kept on painting for herself. However, her 2½ year-old son, Daisei—who is a painter himself today—felt neglected and used to bother his mother, who paid much of her attention to painting.

In Paris the faces of the French people she would occasionally see on the metro were imprinted in Oshima’s memory, and she would put them in her paintings. One day she had an idea, a way for her to play: She decided to try sculpting the faces she had seen in rags or used jersey fabric. Once the pieces were sculpted, she then used her oil paints to paint faces on the fabric surfaces. Her son seemed to feel at ease with his mother working with thread and needles and never bothered her again.

For Oshima the type of art she created, whether paintings or sculpting fabric figures, did not make a difference in the sense of expression she felt. And until today, her thoughts on this have not changed. She did not learn how to make dolls from anyone; rather, for her it was fun to discover the techniques of dollmaking on her own. In 1984 she gave her first solo exhibition at Paris Carrefour du Japon, titled, “Dolls that Could Not be a Human.” It included 20 fabric dolls she saved from her first doll creations. This exhibition gave her the experience of selling her dolls for the first time. In addition, her dolls were introduced to the world through major magazines like Figaro and Elle.

In 1990 another important break came for Oshima when Sloange Strawczynski chose to bring art dolls into the distinguished Paris auction house she worked for, Poulain et Le Fur at Drouot-Richelieu. Strawczynski, who had a good eye for selecting art, persuaded Oshima to enter her dolls in the house’s auctions and was enthusiastic enough about the dolls to purchase one of Oshima’s pieces herself to enter into the auction. This passionate attitude consequently made Oshima direct all of her energy toward this auction, entering the house’s auctions from 1990 to 1996.

For Oshima entering her work in these auctions has been a tremendous challenge and a difficult training ground for her abilities. She knew that if a piece were not bid on even once, the artist would not be invited to the next auction. Therefore, for her to have a consistent income, her pieces would have to be bid on every time. To ensure this outcome, the pieces she entered had to be new and unique for every auction. Oshima continued to put pressure on herself, and as a result, she was able to produce only a few dolls at a time. However, the few dolls she did produce were successful at auction and always fetched high prices.

Among the successful bidders was famous actress and leading doll collector, Demi Moore. Moore’s interest in Oshima’s pieces gave the artist a confirmed confidence in her art and abilities. In addition, Oshima is grateful to Moore for bringing the world’s attention to her work when she was a relatively unknown artist.

Daily life is a treasure box of inspiration for Oshima: life with her children, old photos of family and relatives, memories with friends, children of the world, the flea market, junk from home, books, graphic prints, paintings, requests from a customer, any thoughts about life—these are the sources for her creations. But, of all her motifs, she likes to model her doll after her daughter, Junwa, in her childhood the most.

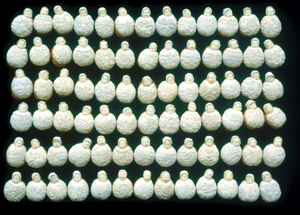

However, “Vœu de Paix” (Prayer for Peace) has become the main subject for her work in recent years. To give shape to the idea, she decided to make a thousand walnut babies with a title. She was inspired to create these dolls when the First Gulf War began in 1991. When the war broke out, she thought about how her work as an artist was powerless against war, and she became badly depressed and almost lost her energy for creation.

The Japanese have a custom of making a thousand folded paper cranes, offering a fervent prayer for the return of health, peace or safety of friends. Oshima followed this custom and put her prayers for peace one by one into each walnut baby. She believes that a baby cannot keep its life without peace in the world. Each of Oshima’s 1,000 walnut babies is one-of-a-kind, with a different face and expression. But in the silence, you will hear them appeal with one voice, “We need peace. We can only live in a peaceful world. Please protect us!”

To make her dolls, she packed rags, and later cotton, in the body made of jersey. Oshima sculpts it by sewing with threads and needles. She once painted faces with oil paints, but later stopped using that technique. To sculpt realistic three-dimensional doll faces, only by sewing, she began to cover the surface with silk “chirimen” (shrunken cloth for kimonos) or silk crapes. She likes this technique because it keeps tension of skin and swelling of flesh sculpted by sewing. She never uses armatures in the bodies, so her dolls are made of only cotton and fabrics, with the exception their eyes, which are made out of terra cotta.

She has continued to work to satisfy herself as an artist as well as an individual. Her latest triumph has been the completion of the thousandth walnut baby for Vœu de Paix on Jan. 19, 2009. The artist was touched by President Obama’s words throughout the campaign and excited when he won. Concerned for his safety, she strove to finish the piece before the inauguration, praying as she made each baby. Now she dreams of sending her babies to travel around the world as a Prayer for Peace″ exhibition.

Oshima believes dolls are a media that appeals to peoples’ emotions over the borders of cultures or languages. Dolls are always associated with the innocence of children and as a symbol of affection between human beings, regardless of cultural and political borders. Therefore, dolls can be genuine ambassadors of peace around the world, and she invites supporters of the project, from any parts of the world.

For more information, e-mail kazuyo.oshima@gmail.com or call (+33) 1 42 71 77 08.