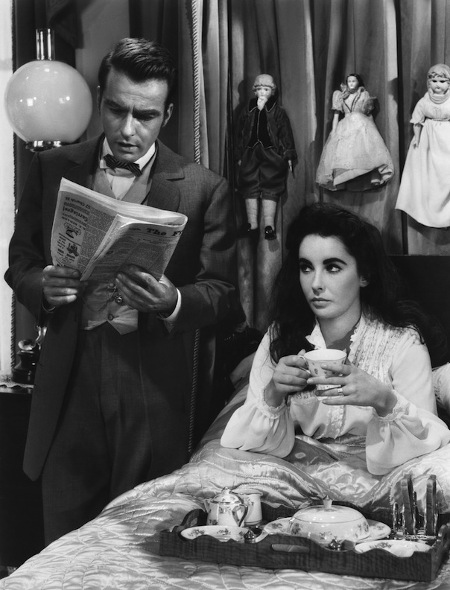

(Liz Taylor tries on her Scarlett O’Hara act in “Raintree County.”)

Photos courtesy of Movie Star News, except where noted

If you are a follower of this blog, you know two sure things about me: I love old movies and I love dolls. When I can blend the two together, I am as happy as a hog in slop, a purring housecat on a sunny windowsill, and a poodle that has unearthed a trove of buried Milkbones. In other words, I am really, really psyched!

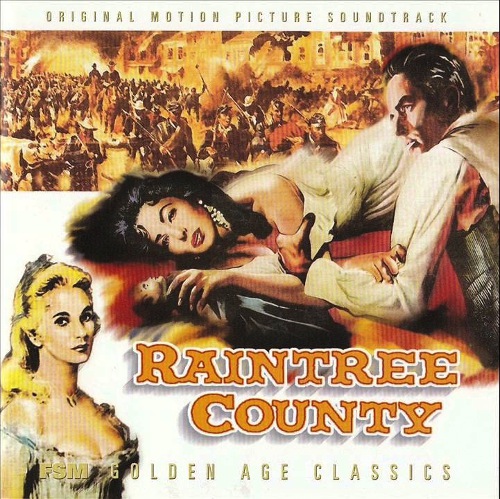

The film that has caught my fancy this week is a 1957 production that has an equal number of enthusiasts and detractors. It is one of those flicks that people either love and defend, or they decry and ridicule. The movie is “Raintree County,” starring Elizabeth Taylor, Montgomery Clift, Eva Marie Saint, Rod Taylor, and Lee Marvin.

The folks who lambast it consider it to be a bargain-basement version of “Gone with the Wind.” They cite the enormous hoop skirts, the corsets and pantaloons, and the number of antebellum mansions and Virginia reel dances. It’s true — there is an unapologetic flirtation with Civil War history combined with a sweeping, first-person romance storyline. However, where GWTW presented a spitfire, indomitable heroine, “Raintree County” offers up a whiny, super neurotic, manipulative female protagonist.

(Liz Taylor plays an unstable Southern belle, who loves dolls more than people.)

Even before her final acts of lunacy and desperation are revealed, moviegoers know that the Liz Taylor character is emotionally and perhaps intellectually limited. How do they infer that? Why, because she is a doll collector, of course!

Yes, once again, a Hollywood prop master had to go on a hunt for dolls to dress and decorate the sets. In “Raintree County,” there are a LOT of dolls to be thrown around the sets. And I mean both figuratively and literally “throw around” the sets.

(This production still is captioned to present Montgomery Clift’s doll smashing as a “heroic” gesture. Come on!)

To sum up the plot in a nutshell, intellectual but unfocused Monty Clift seems to be fated to mate with lovely, sweet girl next door, Eva Marie Saint. His future is upended when Southern belle Liz Taylor comes sweeping into town. They sneak off during a summer picnic, do “the dirty deed,” and then go their separate ways. That is, until Liz returns, declaring that she is with child. Poor Monty is trapped into marrying Taylor, and that is the hell he finds himself wallowing in. Think about his struggle: His character is forced to wed the world’s most beautiful movie star, who is voluptuous, manic, and unpredictable. She’s sexually motivated and seems downright insatiable. Stretching logic, his life becomes such a living hell that he opts to join the army and goes off to fight in the Civil War rather than continue living with the Mrs.

(The “damn dolls” rub Monty the wrong way.)

One of the things that truly enrage the Clift character is Liz’s connection to her hoard of dolls. The things sprawl everywhere. They hang on bed curtains; they slump on nightstands; they sit coolly on chaise lounges and take up the entire marital bed. Monty has always hated these dolls and one night goads Liz into throwing them and destroying them. She participates in this porcelain destruction — loudly shrieking and shrilly laughing — until her most beloved doll gets grabbed for the pitching frenzy.

(It’s a doll showdown as husband and wife square off.)

The doll she loves the best is a horrible, twisted-looking thing. It truly possesses that proverbial face that only a mother could love, and that is one of the clues to the movie’s socially charged revelations.

“Raintree County” is a nearly 60-year-old film, and it is based on a bestselling book from 1948. Its author Ross Lockridge Jr. was celebrated at that time for tackling taboo subjects, but in 21st-century America many of those no-no’s are now everyday affairs. The novel, which was heavily abridged for the screenplay, covers such scandalous topics as premarital sex, nymphomania, psychological imprisonment/asylum commitment, and the mixing of the races. It is the latter hot-button topic that both titillated and alarmed the readers and the movie viewers a decade later.

I recommend “Raintree County” as a curiosity because it was the first time that a Liz Taylor performance was recognized by the Oscar-voting committee. She received her first Academy Award nomination for the film. Taylor later admitted that this was the movie that taught her how to chew up scenery, act volatile and vulnerable, and carry on like a diva on set and off set, too. (During the movie’s filming, she was heavily involved with the big Hollywood producer Mike Todd. He would show up unexpectedly during crucial filmmaking sequences and Liz would walk right off the set into his waiting arms. He’d also send his private plane for her, and she would sneak off to meet him for extended lunches and overnight stays. You can imagine how fellow cast member reacted to her antics.)

(The movie captured headlines due to movie-star antics and a tragic accident.)

Also during this shoot, Monty Clift suffered a terrible automobile accident, which destroyed his matinee idol looks. The film had to cease production while Clift healed and underwent reconstructive surgery. Film buffs like to watch the movie and point out the pre-crash and after-crash montages.

The movie had a very large agenda, and it failed to achieve it. Since the original source material was more of an internal struggle — one man’s reminiscence of his life and times — it might have defeated even the most talented and hardworking creative team. However, due to the bad behavior of its leading lady (running off and vanishing), the horrible maiming of its male lead, and the heavy drinking of many members of the supporting cast, it is quite remarkable that the film was finished and makes any sense at all.

(“Raintree County” was the inspiration for a set of paper dolls by Brenda Sneathen Mattox. Courtesy of fancyephemera.com)

Luckily, Turner Classic Movies is planning to show this Technicolor epic (or train wreck, depending upon your tastes) on Saturday, August 6. Set your DVRs. If you’re a lover of campy movies, you’ll have to appreciate Clift’s total disgust with the doll collection. He denounces them as “damn dolls” and his most intense acting does occur during the doll-demolition scene. As a doll lover, you’ll feel for the poor, unstable Taylor character. True, she’s a wheedler, a liar, a conniver, but, hey, she does love her dolls! It’s awful that she is bullied into breaking what she loves most in the world in order to prove her commitment and attachment to her previously duped husband.

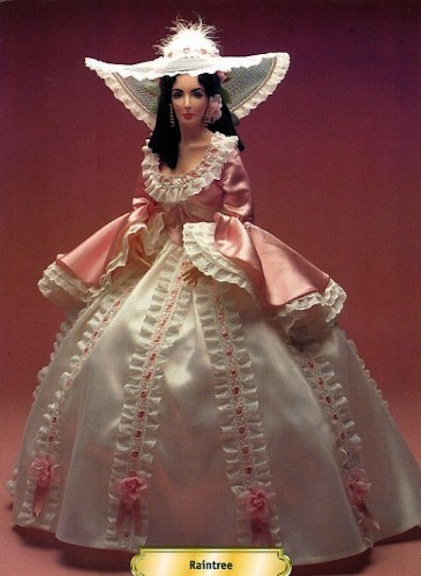

(Legendary doll duo Crees and Coe fashioned this tribute to Elizabeth Taylor in “Raintree County.” Courtesy of Collector Communications archive)

I hope you tune in to the flick and see how once again the world of women and dolls collide with their expected role as wife and supportive spouse. In 1950s Hollywood, there are monster movies being made, espionage films being screened, and sexy potboiler flicks being commissioned. “Raintree County” tries to fit into the sexy potboiler niche, but it has a subtle connection to the monster-movie motif as well. Liz Taylor and her army of dolls have to be eradicated.

(Eva Marie Saint posing with a costume mannequin in between takes.)

The Taylor character is an unwholesome woman and Monty Clift has to be freed from her spell. The hurling of the doll hoard is the first step; it is a way to crack her control of the noble but weak hero. Her ill-fated journey into the swamp to discover the elusive golden raintree of legend is the final way to eliminate her and her influence completely. With her and her dolls broken, busted up, and removed, the hero is free to marry the girl, Eva Marie Saint, who waited patiently and modestly for him.

(In “Raintree County,” doll lovers get the last laugh — or do they?)

It’s a lesson that doll collectors should take to heart: Leading men could beat the Nazis or the Fascists with a single punch in big-screen vehicles. However, they couldn’t stand a chance against a gal and her doll. That’s an alliance that a he-man just couldn’t sever alone.