Rise up, members of the doll community! Truly rise up and flock to see “The Woodsman”. If you are fortunate enough to reside in the New York tri-state region, you can witness it at the New World Stages theater complex. If you live elsewhere, keep your eyes peeled for touring companies or community theaters that will (hopefully) produce this glorious meditation on love, loss, and the fleeting limits of liberty.

For members of the doll community, we know that theatrical and cinematic representations are often disparaging. In earlier postings, I’ve discussed the portrayal of dolls as incarnations of evil, and I’ve covered how the folks who collect and create them are often seen as peculiar, quirky, or downright creepy.

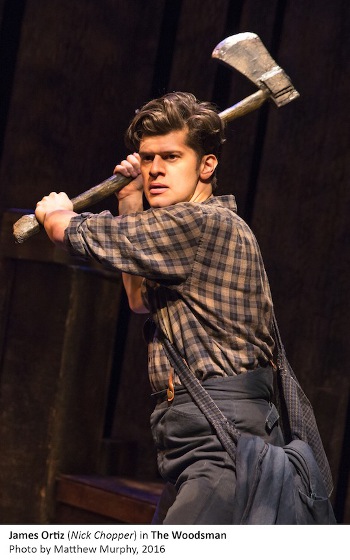

Keeping this in mind, I am always on the lookout for entertainment fare that showcases the enormous amount of talent and creativity needed to make and manipulate a doll. Enter “The Woodsman”. This is a small-scale show that has tremendous heart, which is only right since it examines the fate of a woodsman named Nick Chopper. Before the 75-minute show concludes, this strapping, gentle soul will be turned into the Tin Man from THE WIZARD OF OZ. His metamorphosis from a raw-boned, simple man into an amalgam of hard, metal-edged parts is mesmerizing. What is most engaging is that the transformation of human to cyber surrogate is done through sleight of hand, puppetry, and pantomime acting.

“The Woodsman” is conceived by the play’s leading man, James Ortiz. He and his fellow ensemble players have to emote wordlessly and also breathe life into the assorted stuffed crows, fake flowers and blossoms, and other stand-ins for the natural landscape of where the Munchkins live.

Naturally, since this is a glimpse at Oz before the arrival of Dorothy and her cyclone-bound farmhouse, the tyrant who rules this eastern sector is the horrible despot, the Wicked Witch of the East. She is portrayed by puppets of various sizes and shapes. When she is flying in the skies, spying and dominating her populace below, she is a head on a stick, with a tendril-like cape flying in her wake. It is absolutely terrifying to behold as she swoops across the stage and out over the assembled audience. In her paranoia to exert total control over the citizens who must obey her, she has dispatched an army of informants so that the Munchkins have become afraid to speak.

The loss of words, which leads to the loss of liberty, is also at the heart of this play. (Yes, there is that heart analogy again!) Trembling and scared to be overheard, the plain people of this world have stopped speaking altogether. Language has become a forgotten art. If one does not talk, one cannot be overheard. The farmers, tinkers, and rough-hewn woodchoppers live by this stricture. However, their actions are still out in the open and can be reported upon. This is the awful fate that befalls Nick and the woman with whom he falls in love.

Nimmee, played by Eliza Martin Simpson, is a handmaiden for the Wicked Witch of the East. In bondage and in servitude to the awful ruler, Nimmee is a beautiful young woman who has managed to retain a spirit of humanity and optimism. When her path crosses with Nick’s, they are instantly attracted to one another. They fall in love and Nimmee literally receives Nick’s heart — a necklace in the shape of a Valentine, which had belonged to his mother. This physical exchange leads to their downfall. The young lovers are in the crosshairs of a jealous and enraged witch.

To act out a play that throbs with ill-fated, star-crossed lovers is often a challenge for even Shakespearean troupes. It asks the audience to believe that two performers could meet and fall effortlessly and genuinely in love before your eyes, and before the first-act curtain falls. Here, Nick and Nimmee have no impassioned dialogue to recite. They don’t have soliloquies, monologues, or even smatterings of text to share. They must act out their feelings, and it is truly — here it comes again — heartbreaking.

The company members who handle the full-body puppet version of the witch do a remarkable job of moving her about the stage. She is realistic in her mannerisms and in her wrath. Her hands are clawlike and her anger is bearlike. She is a tornado of envy, hatred, and contempt. Her behavior is spoiled and childlike when she lashes out and hexes the two lovers.

Since this is a prequel to the Oz classic, there are no witnesses who are surprised when Nick Chopper — his name alone is a giveaway — becomes the Tin Man. However, the way it is staged, with Nick’s ax magically turning against him, rendering him limbless and eventually headless, is a wonder to behold. As he loses his body parts, the character’s arms and legs are replaced with operable puppet parts. Finally, the last heart-stopping scene is the Tin Man, alone and forlorn, trapped in his steel encasement. He is “alive,” but he is not living. He has lost his love, his life, and his liberty. There is definitely a hush that descends over the audience. We, too, have had our words stripped from us. This is a spiteful, wicked comeuppance that defies any kind of verbal defense.

If you have the chance to see this play, I urge you to attend. It is definitely a celebration of the doll-art world. The actors who play the many parts — Munchkins, tinkers, Ma and Pa, Nick and Nimmee — have to seamlessly interact with their nonhuman counterparts. This abandonment of usual “adult rules and regulations” allows the actors to play freely and openly on the stage. They can cower at the sight of a head on a stick, wrapped in fabric. They — and we — can weep at a human-scale puppet that is doomed to spend an eternity unloved and abandoned in the forest.

Emotions are difficult to convey, and the actors are assisted in their performances by a violinist (Naomi Florin) who accompanies their action with a forlorn and desperate score composed by Edward W. Hardy. Other members of the ensemble snap their fingers, stamp their feet, and hum to show fear, anxiety, and the ever-escalating dread that encompasses Nick and Nimmee.

The witch actresses, who carry the large puppet about, hiss and snarl and are fearsome in their animalistic noises. They convey her primitive and primeval needs. If ever a person wants to see what is the connection between soft-sculpture art and freedom of expression, “The Woodsman” is the play to see.

Because it involves the participation of humanity meeting puppetry, it could be easily dismissed as a Sesame Street retread. However, its maturity and insight into what makes us human — and can we ever be completely stripped of that spark — will linger for a long time. As a doll enthusiast, and a theater lover, this is what the figural-art movement is all about. Please, James Ortiz and company, consider bringing this on the road. And, for those who have seen it, we know the power of the word “please” in this enthralling tale.