Every so often, I’ll meet someone who will be tickled pink that I work with dolls. After answering the obligatory North Pole and Santa’s Workshop questions—I telecommute, I explain, so I don’t need to check in with the reindeer on a daily basis, and yes, Rudolph’s nose IS that shiny—I explain how the world of dolls is actually quite huge, innovative, constantly re-inventing itself, and can be quite profitable.

When the issue of capital is raised, so are the eyebrows.

For lots of people, dolls are either manufactured toys that come to market through some mysterious means, or they are hobbies and crafts with a decidedly female twist. With the exception of the big titans of toys—Mattel, Hasbro, and Jakks—most people don’t consider how toys are created, who designs them, who distributes them, and who sells them. They are a business, but they are so often relegated to something “fun and frivolous,” “quirky and peculiar.”

It’s almost as if the men and women who toil as independent doll artists are regarded as Martha Stewart wannabes: they’re seen as sitting atop a pile of embroidered pillows, sampling bonbons, and knitting and crocheting for the fun of it.

Quite the contrary, Messieurs and Mesdames. Doll making is hard, and it has a proud history of uplifting successful purveyors from poverty to wealth. Take that, Adam Smith! (Sorry, I’m caught up in all the 2012 pre-election tailgating.)

It’s undeniably true, however, that doll designing does have the power to change lives: not just by spreading happiness to the children and adults who get the finished products, but by physically lifting its participants from one tax bracket to the other. And that notion of being independent and self-actualizing should be applauded.

independent and self-actualizing should be applauded.

Many, many years ago, a TV movie called “The Dollmaker” showed how an uneducated but enterprising woman was able to save her family during depression days. Unschooled and seemingly without hope, she uses her finesse with an ax, her talent as a whittler, and her mother-bear survival skills to keep her family fed and alive. They manage to have their home saved and their bellies filled because of the power of a doll. Starring Jane Fonda as the homespun woman with grit and gumption, the movie celebrated feminism and liberation. Equal parts “Norma Rae” and “The Grapes of Wrath,” it was a slice of history with a side dish of sentimentality. (Lots of slow-motion shots of wood being split apart and needles being threaded.)

Interestingly, the economic salvation of a family via doll crafting is the basis of one of America’s most beloved doll figures: Madame Beatrice Alexander.

Born to immigrants in New York City, Beatrice (she named herself that, because it sounded more regal, and also gave herself the “madame” moniker) and her sisters fashioned replicas of Red Cross nurses to sell during World War I. These cloth dolls became a sensation, and helped to fill the family’s coffers, and set her on the path of becoming a female entrepreneur during a time when most women were relegated to domestic drudgery. Dolls helped Alexander to achieve legendary status as a doll designer, businesswoman, factory owner, and living American legend. Quite the feat! (And the Red Cross nurse, who helped to launch it all, has popped up over the decades in the Alexander lineup.)

Born to immigrants in New York City, Beatrice (she named herself that, because it sounded more regal, and also gave herself the “madame” moniker) and her sisters fashioned replicas of Red Cross nurses to sell during World War I. These cloth dolls became a sensation, and helped to fill the family’s coffers, and set her on the path of becoming a female entrepreneur during a time when most women were relegated to domestic drudgery. Dolls helped Alexander to achieve legendary status as a doll designer, businesswoman, factory owner, and living American legend. Quite the feat! (And the Red Cross nurse, who helped to launch it all, has popped up over the decades in the Alexander lineup.)

Today, the spirit of freedom through doll making is alive and well; and it has recently been highlighted in Vietnam.

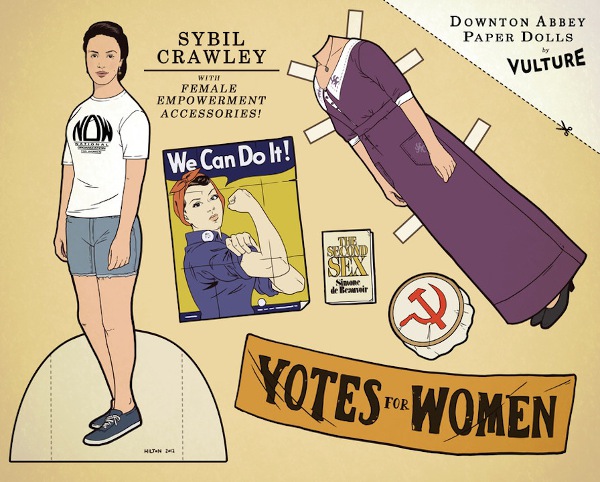

A very touching story came to light about a 22-year-old student who received a paper doll as a gift when she was 17 and decided she would try her hand at fashioning one. Fast-forward five years, and 5,000 dolls later, and she is the proud owner of a burgeoning cottage industry. She is elevating her family from dire financial straits through her doll determination.

The young woman, Nguyen Thuy Duong, creates an exotic spin on the traditional paper doll, and sells these for an attractive $3 to $10 a pop. Currently assisted by her family, she dreams of opening up the business to centers where handicapped people can learn how to make the dolls as well, and will give them monetary hope and personal satisfaction.

Shopping at her local Hang Ma Street, and also importing items from Japan, she is determined to create dolls that capture every nuance of life. She wants to make paper dolls that reflect brides on their nuptial days, girls starting their first day at school, jazzy teenagers looking contemporary and chic, and historically accurate dolls in sweeping costumes with windswept hair.

Shopping at her local Hang Ma Street, and also importing items from Japan, she is determined to create dolls that capture every nuance of life. She wants to make paper dolls that reflect brides on their nuptial days, girls starting their first day at school, jazzy teenagers looking contemporary and chic, and historically accurate dolls in sweeping costumes with windswept hair.

Beyond that, she wants to make sure that her life and the life of her family and community are improved.

Creativity, accountability, and capitalism come to Vietnam: and in this one little home, on this one little street, in this one little town, the future is in the hands of a beautifully crafted doll.