The Helen Vernet doll by Monica Reo

Getting a letter from Monica Reo is always a joyous occasion. My doll artist friend never takes a break from researching and creating dolls that tell a story through their wigging, costuming, and lifelike demeanor. This month, she’s unveiled a doll that exposes an often-overlooked part of feminist history. While suffragettes waged war to acquire the right to vote, British businesswoman Helen Vernet toiled to get the right to place wagers. Yes, Vernet was the first officially licensed female bookmaker in Britain, and Reo has dug up her biography and honored her with a Helen Vernet doll.

“Up until World War I, the betting rings at Ascot and beyond were the exclusive domain of men only,” Reo revealed to me. “That is, until the socially connected and upper-class Helen Vernet became the first woman to pass the ‘fit and proper’ character test required to obtain a bookmaker’s license.”

Eliza enters the Ascot Races in “My Fair Lady,” starring Audrey Hepburn, courtesy of Warner Bros. Deluxe Boxed Set.

The folks who cheer on the ponies at racetracks around the world are definitely a colorful set. Think of the flamboyant characters in “Guys and Dolls,” the musical comedy that makes sport of dedicated, seemingly irredeemable gamblers and the molls that love them. While Damon Runyon’s guys and their dolls were not very refined, and certainly rough around the edges, the British swells who attended the Ascot races in “My Fair Lady,” circa 1913, are more akin to the people that Helen Vernet rubbed shoulders with.

“Loving the horses, Helen was a bright and beautiful fixture on the racing rail. She was the perfect blend of class and vitality, possessing both life and uncanny wit,” Reo stated. “Helen also had an incredible mind of her own, encompassing all things in her life.”

The Ascot racecourse in the years after World War I, courtesy of Monica Reo

Interestingly, right after the Great War, Helen had attempted to kick off a career as a bookmaker. She had many well-connected friends, was popular in her social circle, and was known to enjoy small talk and collecting small bets on behalf of her female friends. Soon, though, her self-starting ways gained the attention of the authorities and she was warned to stay away from the world of wagering. She wasn’t a professional odds maker, and her penchant for gambling drew suspicion to her behavior and her gender.

Barbie in her “My Fair Lady Ascot” gown, courtesy of Mattel

She also caught the attention of Arthur Bendir, who had been running a gentlemanly bookmaking firm since 1902. Bendir, a master of mathematics, put two and two together and came up with a fortune. In 1918, he tapped Vernet to join his company, which was called Ladbrokes. She was commissioned to work as a bookmaker specializing in the “fairer sex”—shades of “My Fair Lady”—and their well-heeled fathers, husbands, and lovers. Bendir was betting that a woman of impeccable background and breeding would be trustworthy and, therefore, a guaranteed moneymaker.

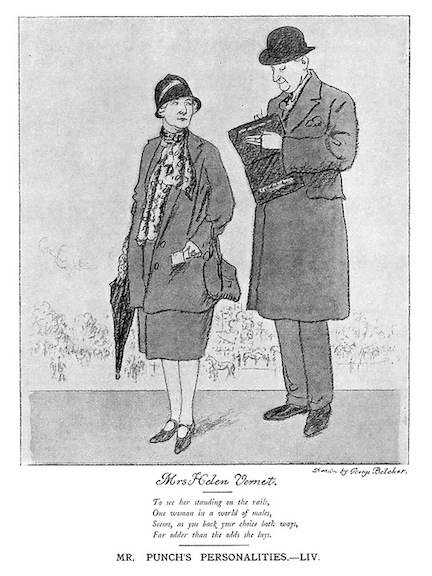

George Belcher’s “Punch” drawing and poem pay homage to Helen Vernet.

In 1928, after a decade of proving herself, Vernet became a partner in the firm. She took her betting seriously, and stood out in this horseracing circle due to her femininity. In fact, “Punch” magazine cartoonist George Belcher illustrated her polite demeanor and mature professionalism in his popular “Mr. Punch’s Personalities” column. In 1927, he wrote an ode about her, too, which accompanied his drawing of her at age 50+. The poem wryly states: “To see her standing on the rails/One woman in a world of males/Serene, as you hand your choice both ways/Far odder than the odds she lays.”

The famous Ascot Gavotte scene from “My Fair Lady,” courtesy of Warner Bros.

Reo was especially taken with the garments that Helen chose when she trekked among the gambling elite. Being a fixture at Ascot from the days of Eliza Doolittle right up to Elizabeth Taylor (Vernet passed away in 1956), Vernet chose clothing that spoke to her moneyed background as well as her incomparable independent streak. “Her early fashion style had a nod to bohemian influence, but nothing ever to sully her ‘fit and proper’ character assessment,” Reo declared.

Reo’s homage to the boundary-breaking pioneer—a woman who truly strode alone through a man’s world—is decked out in a gorgeous ensemble that speaks volumes about this woman’s confidence and individuality.

Full body look at Helen Vernet doll by Monica Reo

“True to 20th-century couture, her unique day fashion was designed exclusively for her,” Reo observed. “It has shades of vibrant burgundy and gold, with soft blond fur, wool, and gold-beaded accents. Helen stands on a handmade matching tapestry-covered, wood-accented base. She is ready to take her place at the Ascot races!”

The back of Helen Vernet’s stunning ensemble designed by Monica Reo

A fan of Edwardian dramas and comedies, Monica Reo is smitten by the opulent fashions, intricate coiffures, and bygone behaviors of the onetime stiff-upper-lipped upper echelon. These swells who resided in the upstairs lodgings, lording it over the downstairs dwellers, have vanished into the ethos of legend. Their etiquette and elegance are now part of costumed TV shows and films, which Reo and the rest of us watch with fascination.

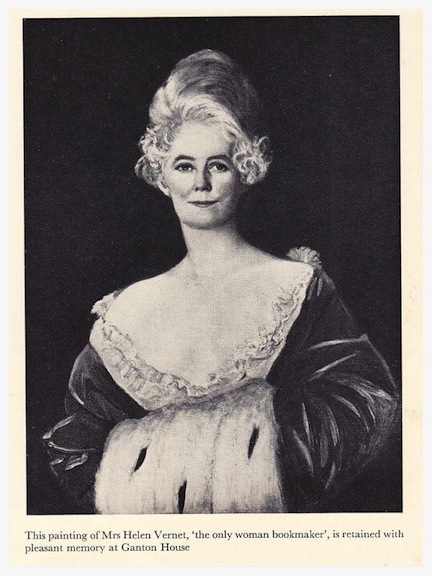

A portrait of Helen Vernet, which hung at Ganton House, courtesy of Alchetron

These individuals and their stories remind me of that famous opening line from L.P. Hartley’s “The Go-Between,” a 1953 novel that cast its keen eye to a long, hot summer in 1900: “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” They do, indeed.