The other day, my daughter, who is 6 going on 36, announced that she had to write a paragraph in school about her future plans and ambitions. That’s a great deal of forward-thinking for a bunch of first graders. Jane was very pleased with herself because she poured out her energy into composing a look at her life as a chemist/scientist.

However, as she was regaling me with her futuristic résumé, she seemed to be smiling like the cat who devoured the proverbial canary—or maybe the cat who lapped up the cream. It’s a much nicer simile.

“What’s up with the grin, Jane?” I asked.

She replied, nearly bursting with her own cleverness, “This was just a cover. I’m really going to be a secret agent; but if I said that, everyone would know, so I had to come up with something else.”

And with that kernel of truth confirmed—deception is a spy’s most trusty tool—she left to go upstairs and play with her Pixie Hollow fairies. (They’re all members of a secret society of winged agents who battle criminals, solve mysteries, and preserve law and order. This is her own invention, sort of a “CSI: Never Land” edition.)

And with that kernel of truth confirmed—deception is a spy’s most trusty tool—she left to go upstairs and play with her Pixie Hollow fairies. (They’re all members of a secret society of winged agents who battle criminals, solve mysteries, and preserve law and order. This is her own invention, sort of a “CSI: Never Land” edition.)

When I heard Jane offer up her very tricky ruse—doing one thing and calling it another—I immediately thought of the whole furor that still heats up occasionally regarding “doll artist” vs. “figural artist” vs. “soft-sculpture artist” vs. “doll maker.”

Are all of these labels one and the same, or is there a distinct difference among the ladies and gentlemen depending on what they label themselves?

Many years ago, I heard someone (who shall remain nameless) stand a few inches from my face and explain how men are definitely “artists,” whereas the women are “makers.”

This person opined that women tend to personalize and imbue their creations with backstories and fictional histories and coo over them, and act as if every finished product was a matter of birthing. The men, however, were more objective and worked on honing their craft, capturing lifelike muscles and movement, and created beautiful works of art that stood on their own merit—no personalities or storylines required.

and act as if every finished product was a matter of birthing. The men, however, were more objective and worked on honing their craft, capturing lifelike muscles and movement, and created beautiful works of art that stood on their own merit—no personalities or storylines required.

Channeling my inner Gloria Steinem, but making sure I didn’t tread on any toes, I tamped down my feminist knee-jerk reaction and tried to talk with this jerk on some kind of human-to-human level.

No luck. The opinion was set in stone.

According to this conversationalist, all men with a kiln were doll artists; all women were doll makers! Well, if we hopped aboard this train of thought, it wasn’t the talent that pulled the freight or chugged the engine. It wasn’t the genre, but rather the GENDER alone that distinguished who should be accorded this special accolade.

So I ask, what does make the difference in these word choices? What makes someone a “maker” as opposed to an “artist?”

In show business, is there a difference between the “film industry” and the “movie industry”?

In show business, is there a difference between the “film industry” and the “movie industry”?

There was a time when “film” seemed to suggest something more artistic and insightful. Perhaps it was what one would watch in a college course that celebrated Scandinavian celluloid soul-searching: lots of Ingmar Bergman—not so much Ingrid Bergman.

And movies? Well, that seemed to be applied to escapism versus existentialism. Popcorn and soda pop, mounds of M&Ms—that seemed to be the real purpose behind movies. It’s a way to entertain you while you handed over your hard-earned cash at the candy counter.

I suppose a movie was two hours’ worth of empty, mental calories: not a lot of heavy thinking required. A film was supposed to nourish the soul.

But that distinction has blurred, and I hear schlock-meisters like Michael Bay, the “genius” behind the “Transformers” flicks, described as a filmmaker.

More to the point, when Steven Spielberg creates a picture like “Jaws” or “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” is he making a movie? But when he stands behind the cameras for “Schindler’s List,” is he suddenly making a film? Does he wear both hats—or in his case, both baseball caps?

stands behind the cameras for “Schindler’s List,” is he suddenly making a film? Does he wear both hats—or in his case, both baseball caps?

It gives me something to consider when I talk about my collecting and my day-to-day work in the doll world.

Do I have to bite my tongue and apologize if I call a certain artist a “doll maker”? Do I have to defend my position if I say someone is a “doll artist,” and she sees herself as a “figural sculptor”?

What’s the difference? And does it make a difference to you—the readers of the magazine and of this blog, the collectors of the dolls (aka “artwork”), the artists/sculptors/doll makers? Where do you stand on this issue?

What’s the difference? And does it make a difference to you—the readers of the magazine and of this blog, the collectors of the dolls (aka “artwork”), the artists/sculptors/doll makers? Where do you stand on this issue?

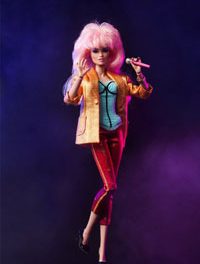

I’d love to hear from an array of people who are immersed in this field, and find out what makes you implode or explode. In the world of doll artistry, does the prefix of “doll” automatically diminish its significance? And in the world of doll commerce, does the notion of “an artist’s original” immediately add to its monetary cachet? And if a Mattel Barbie is swaddled in the mantle of a Gustav Klimt painting, does it rise in meaning?

Let’s discuss, in an artful way, naturally!