(Hugo Ball, known as the father of the Dada movement, dressed as part man and part machine.)

Photos courtesy of National Gallery of Art

The other day I was in our car and the classic Police song “De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da” came on the radio. Since I’ve heard that song repeatedly over the past 35 years, I took it in stride. Maybe I hummed along, or perhaps I even warbled a couple of the nonsense syllables, but my daughter and her friend found the lyrics to be hilarious. At ages 10 and 11, they consider themselves to be the arbiters of musical taste, and this ditty obviously didn’t rate high in their estimation. They kept giggling about the sound of “do do,” implying that it had to do with bodily waste, and the “da da” made them laugh uproariously about infants and baby talk. As they discussed what the song could possibly mean, I got to thinking about Dada, and I’m not talking about my father or theirs.

Dada is an art movement that came to light during World War I. It was birthed as a reaction to society’s growing reliance on machines and technology. The Great War — known as that, because who could ever assume a second one was lurking on the horizon — changed the way warfare was conducted. Fatalities were enormous; maimed and seriously injured soldiers were countless; weaponry spiraled into an unthought-of world of aviation, poisonous gases, and devices that were the stuff of nightmares. Artists, naturally, responded to this conversion of humanity into something inhuman and perhaps robotic.

(Klaus Nomi, singer and performance artist, kept the spirit of Dadaism alive into the early 1980s.)

The Dada salon of artists — painters, sculptors, philosophers, and performers — is frequently said to be the brainchild of Switzerland-based Hugo Ball. Ball founded an intellectual coffeehouse of sorts — a nightclub where poetry would be read aloud, people would dance to an orchestra that played no sounds (they sat with their instruments idly propped against them), and costumes would be built to both inspire and challenge the audience. (If anyone is familiar with the late Klaus Nomi, a close friend of the late David Bowie’s, you know what these Dada-esque outfits could look like.)

However, another pair of people is also deeply responsible for helping to launch the Dada art phase. And, interestingly, both of these people are women — and both are connected to dolls.

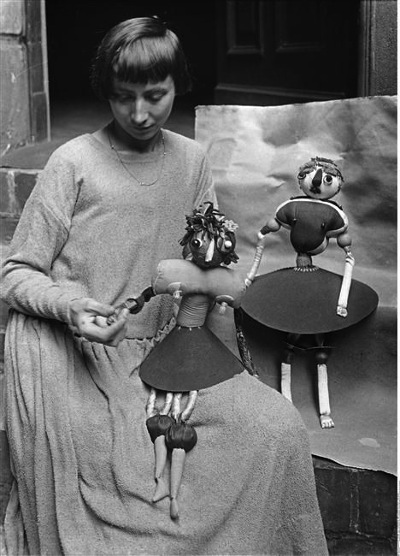

(Emmy Hennings developed a following for her truth-talking doll act at her and her husband’s cabaret.)

Ball’s wife was the poet Emmy Hennings. At her and her husband’s nightspot, the Cabaret Voltaire, Hennings often took the stage. However, it wasn’t like Ricky Ricardo doing all he could to prevent Lucy from storming into the Club Babalu. (Hey, “Babalu” has a sort of Dada feel to it, too!) No, Hugo Ball welcomed Hennings’s performances, which were extremely eccentric. Besides recitations of her poems and essays, she also did a song-and-dance act that included her partner, a rather frightening-looking hand puppet/doll. Hennings would allow the doll to say things that were shocking and would make the audience guffaw loudly and nervously. A doll — a so-called child’s plaything — being manipulated by a woman, who was obviously mouthing the outrageous comments, was a mind-blowing display to these Zurich swells. Hennings and her doll completely took the notion of what women were meant to be, what they were expected to say, and then gave it a naughty, cynical, and sexually charged theme.

(Hannah Höch is one of the co-mothers of Dadaism.)

Another woman who was extremely instrumental in the Dada world was Hannah Höch. Höch went by her first name Hannah, which was an assumed name. Born Anna Therese Johanne Höch, she changed her name to Hanna, and then added a final “h” to it so her name would become a palindrome. (A palindrome is a word or sentence that is spelled the same frontward and backward, like Hannah.) Hannah loved the idea of a palindrome because it zeroed in on the motif that she most liked to confront in her paintings and in her photo montages.

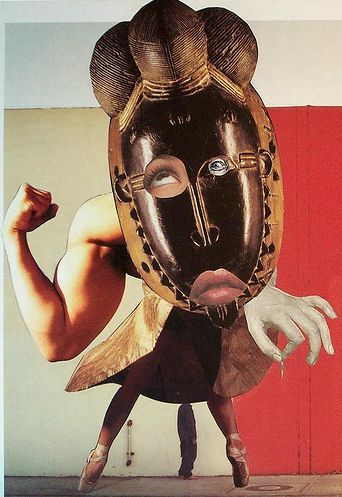

(One of Hannah’s many astonishing, self-examining self-portraits.)

She loved to show how people, places, and things were often unexpectedly the same. In her collages, she would blend parts of different people’s anatomies — merging together different genders, ages, races, and cultures. Her viewpoint was that many people are often taken at face value and their similarities are often overlooked. She showed that off in her many self-portraits that would mix up parts of her face or body with African tribal symbolism, male appendages, and even pieces of machinery.

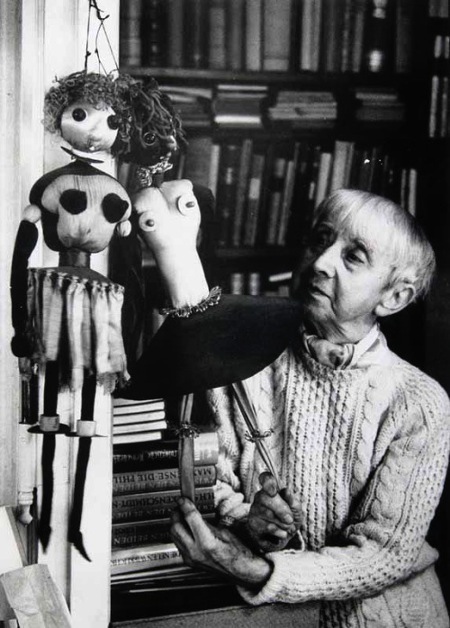

Hannah also achieved a great deal of fame and notoriety for her Dada dolls, which she first constructed in 1916. These dolls were made from fabric, yarn, thread, boards, and beads. They did not represent sweet toddlers or lovely ladies. Rather, they were creatures that seemed to reflect futurism, tribalism, primitivism, folkloric attitudes, as well as cutting-edge sensibilities. They did not resemble a traditionally made European dolly.

(Dada dolls made by the talented Ms. Hannah.)

Now, in 2016, a hundred years later, the works of Emmy Hennings and Hannah Höch do not seem outrageous or unsettling. Over the past century, we’ve seen their pioneering performance art and cut-up artistry copied time and time again. Their groundbreaking take on female self-expression and Dada techno-rejection has influenced folks who number among the elite artists and musicians of today. Photographer Cindy Sherman has credited them for her award-winning work as a chameleon in front of and behind the camera. Patti Smith has acknowledged their unbridled ferocious creativity, as have Debbie Harry and Chris Stein of Blondie. Art critics have often dubbed these two early-century women the “godmothers” of the punk scene.

(In 1975, Hannah Höch, age 85, poses with two Dada dolls.)

Think about it: one hundred years ago, in 1916, two women were speaking truth to power, breaking down gender and racial stereotypes, and questioning why the world was rushing headlong into machine automation over human veneration. It sounds like much of what they were ruminating about back then, and boldly exploring, could still hold center stage today.